eBook - ePub

Georgia's Foreign Policy in the 21st Century

Challenges for a Small State

Tracey German, Kornely Kakachia, Stephen F. Jones, Tracey German, Kornely Kakachia, Stephen F. Jones

This is a test

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Georgia's Foreign Policy in the 21st Century

Challenges for a Small State

Tracey German, Kornely Kakachia, Stephen F. Jones, Tracey German, Kornely Kakachia, Stephen F. Jones

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The South Caucasus is the key strategic region between the Black Sea and Caspian Sea and the regional powers of Iran, Turkey and Russia and is the land bridge between Asia and Europe with vital hydrocarbon routes to international markets. This volume examines the resulting geopolitical positioning of Georgia, a pivotal state and lynchpin of the region, illustrating how and why Georgia's foreign policy is 'multi-vectored', facing potential challenges from Russia, int ernal and external nationalisms, the possible break-up of the European project and EU support and uncertainty over the US commitment to the traditional liberal international order.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Georgia's Foreign Policy in the 21st Century an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Georgia's Foreign Policy in the 21st Century by Tracey German, Kornely Kakachia, Stephen F. Jones, Tracey German, Kornely Kakachia, Stephen F. Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Diplomatie et traités. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

THE USES OF IDENTITY IN GEORGIAN FOREIGN POLICY

Chapter 1

ACHIEVING SECURITY AS A SMALL STATE

Small states face difficult decisions about the nature of their economic and political interaction with their neighbours and regional partners. This is more complex for the post-Soviet states such as Georgia, which, since independence, have had to establish a new global role for themselves. Small and weak in terms of size and capability, Georgia was not initially viewed by the international community as an important state, despite its presence in a strategically located region between Russia and the Middle East. This was compounded by its lack of any experience in international relations or its possession of the prerequisite instruments of policymaking. Georgia faced the complex task of determining the most appropriate geopolitical strategies vis-à-vis its immediate neighbourhood, as well as towards non-regional actors like the European Union (EU), the United States and NATO.

Since 1991, Georgia’s approach to foreign policy has been shaped by its status as a small state. Its key foreign policy objective – with variable intensity and success – has been the preservation of sovereignty and territorial integrity within internationally recognized borders. Georgia has pursued a foreign policy that removes it from the Russian sphere of influence. It has sought to develop a democratic state in line with Western values and standards, under the protection of a Euro-Atlantic security umbrella. In spite of persistent diplomatic, economic and military pressure from Russia, there has been little substantive change in Georgia’s foreign policy position for over two decades: even in the wake of the 2008 war with Russia, the pursuit of NATO membership and a closer relationship with the EU has remained a central pillar of Georgia’s foreign policy, and Tbilisi has deliberately courted the West, particularly the United States, in an attempt to counterbalance Moscow’s influence. China, along with Azerbaijan and Turkey, have also become increasingly important for Georgia in recent years, as Tbilisi seeks to diversify its trade partners and markets, as well as its diplomatic links.

Georgia is an interesting country for scholars of foreign policy and international politics. Since regaining independence in 1991, the Black Sea country has experienced multiple wars, conflicts and shifting alliance structures, against a backdrop of a rapidly changing international environment.1 Georgia provides food for thought for each of the major disciplines of international relations and foreign policy analysis. Supporters of the power politics approach to international relations will be intrigued by Georgia’s partly structure-deviant behaviour, i.e. not to bow to Russia’s systemic pressure despite the absence of viable alternatives. To scholars of social constructivism,2 Georgia offers interesting opportunities to explore how normative ideas shape foreign policy and whether they can trump rational behaviour based on a cost–benefit analysis. Finally, Georgia offers scholars who focus on domestic drivers of foreign policy a rich laboratory to explore various unit-level triggers of foreign policy, such as ideas, perceptions, public opinion and non-state actors.

This chapter explores the foreign policy behaviour of Georgia through the lens of the existing literature on small states. What are the diplomatic strategies Georgia uses to secure itself, advance its interests, and ensure its survival in an unstable neighbourhood? As a small state squeezed between powerful neighbours, does it have any freedom of action in its foreign policy? Traditional theories of the foreign policy behaviour of small states suggest that they tend to either ‘bandwagon’ with great powers or ‘balance’ against them. The example provided by Georgia demonstrates a far more nuanced set of foreign policy behaviours than these theories suggest. A number of scholars of Georgia’s foreign policy prefer to use neoclassical realism as a framework for analysis. Neoclassical realism posits that, while the international system remains the most important driver of foreign policy for states both large and small, it is unit-level factors that shape the responsiveness of states and translate system-level variables into policy outcomes.3 Studies exploring Georgian foreign policy through this lens focus on the impact of a variety of domestic issues including the significance of elite cohesion, elite identities, state capacity, political paternalism and religiosity, as well as ideologically informed elite perceptions.4

Despite a growing focus on the role of small states within the post-Cold War international system, there is a gap in the literature on the foreign policy behaviour of small states in the post-Soviet area. Much of the work on post-Soviet small states tends to focus on how they manage their relations with Moscow first and foremost, portraying them as vulnerable foreign policy ‘recipients’; less attention has been directed towards the more positive aspects of their foreign policy behaviour. Small states are often located within the orbit of a larger power, and are defined by their relative lack of influence and capabilities. One way that they can secure themselves and get noticed in a world of growing great power competition and numerous small state rivals is to make themselves useful to bigger powers. They can demonstrate their strategic utility and reliability as ‘trusted partners’ in order to influence the perception of others about their standing within the international community.5 This chapter contends that a significant focus of Georgia’s diplomatic efforts has been to signal its status and reliability as a ‘trusted partner’ to the international community, and to reposition itself within both the global and regional hierarchy. The Black Sea state seeks to demonstrate its strategic utility to the broader international community in a variety of ways: firstly by using its military capabilities to contribute to international stabilization operations such as the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan, in order to enhance its standing within the global community. This illustrates its standing as a ‘good partner’ for the West, despite facing a significant military threat to its territorial integrity; secondly, Georgia capitalizes on its geographic location, which is simultaneously a fundamental strength and critical vulnerability, to establish Georgia as a transit hub between Europe and Asia. Georgia might be a small country in terms of territory, but it is increasingly important as a strategic corridor and international partner. Finally, it has also been seeking to recast itself as a reforming ‘European’ state, explicitly differentiating itself from its Soviet past in order to be accepted as part of a broader Euro-Atlantic security bloc.

Defining small states

There is little scholarly consensus with regard to the definition of a small state. There is a range of terminology used to describe states that are not ‘great’ powers: small states, small powers and weak states are just some of the terms used, all of which have very different definitions that tend to focus on tangible and intangible aspects, including physical attributes such as size of territory or population, economic indicators and capabilities, as well as the capacity to influence, or a state’s role in the international hierarchy.6 Nevertheless, there is acknowledgement that the principal variable is a state’s position in relation to others, as opposed to a material variable such as population size and territory. According to Archer et al., a small state is ‘the weaker one in an asymmetric relationship, which is unable to change the nature or functioning of the relationship on its own’.7 This emphasizes the relational aspect: ‘a small state typically acts simultaneously in a number of different power configurations with different sets of actors, and therefore a state may be weak (“small”) in one relation, but simultaneously powerful (a “great power”) in another’.8

Thus, small states tend to be characterized in the scholarly literature as the weaker part of an asymmetrical relationship. A focus on material capabilities to conceptualize state size is useful up to a point, as it offers ‘analytical certainty’. But when it comes to definitions, this becomes less useful as it does not explain the behaviour of one state toward another.9 Are the diplomatic strategies employed by small states merely about ensuring security and survival, or are there other motivations that explain their foreign policy behaviour? To develop a comprehensive understanding, it is helpful to combine an objective, capabilities-based approach with an explanation of state behaviour, focusing on the drivers of international engagement and activism.

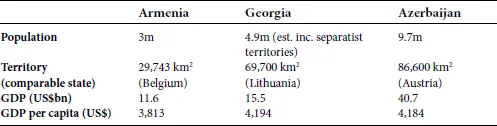

Based on material attributes such as population size and territorial area the states of the South Caucasus could be classified as ‘small’ states, as set out in Table 1.1 below. Their capacity to influence other states is limited. However, within the region there is a different set of power configurations. As an example, Azerbaijan is relatively ‘small’ in its relationship with Russia, the ‘weaker part’ of Archer et al.’s asymmetric relationship, but is simultaneously powerful in its relations with its two small state neighbours in the South Caucasus, Georgia and Armenia. Asymmetric power relationships are common across the post-Soviet space: Russia remains the dominant power in the region, in military, diplomatic and economic terms. For example, the economic relationship between Russia and the majority of the post-Soviet states tends to be asymmetrical, with Russian companies often the key investors, and Russian goods comprising a large percentage of imports for such states. In large part, this reflects the enduring legacy of Soviet economic links, what Libman has termed the ‘inevitable inertia of Soviet economic ties’.11

Table 1.1 Comparing the states of the South Caucasus

Source: World Bank.10

While small states are vulnerable to external pressure, post-Soviet states are perhaps more so because of durable legacy ties such as economic and societal links, combined with the fact that they remain geographically adjacent to the successor state of the former imperial power. This is reflected in a lot of the literature on the foreign policy of post-Soviet states, which tends to focus on their relations with Moscow and the need to seek compromise as the weaker part of an asymmetrical relationship. Mouritzen proposes a strategy of ‘Finlandisation’12 or ‘adaptive acquiescence’ (making the best out of political and strategic dependence) for the smaller neighbours of strong regional powers with adjacent spheres of influence. He suggests that post-Soviet states on the Russian periphery are worse off and ‘will need to come to terms with their larger neighbour (if, perhaps, after a short period of defiance)’.13 The problem with this approach is the lack of agency assigned to small states. Small states do have choices in their foreign policy behaviour, they are not mere pawns of bigger states. If this were the case, Georgia would have acquiesced to Russian demands and changed its foreign policy stance after the persistent pressure from the Kremlin (particularly in the wake of the 2008 war), abandoning its overt ambitions to integrate more closely with the West, accede to NATO and ‘return to Europe’. Instead of acquiescing and recognizing what scholars such as Mouritzen propose, Tbilisi has continued to state its NATO membership ambitions, and in 2014 signed an Association Agreement with the EU, setting up a bilateral Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) – in direct defiance of what Moscow wanted. This lends credence to the approach of Cooper and Shaw, who emphasize the resilience and resourcefulness of small states rather than their vulnerability.14 Thus, while existing work on small states in the post-Soviet space tends to focus on the vulnerability of these states and the need to accommodate Russia, this does not provide clear answers with regard to Georgia’s foreign policy behaviour.

The literature on the status-seeking activity of small states is a useful tool for analysing Georgia’s foreign policy behaviour. De Carvalho and Neumann assert that status is a key driver in the policies of small states, who ‘suffer from status insecurity to an extent that established great powers do not’.15 Status is defined as a state’s standing or rank within a status community, which is related to the collective beliefs about a state’s position within a global or regional community. It is less to do with a state’s material capabilities than with its ability to influence the perceptions of others about its standing.16 Wohlforth et al. identify two objectives of small state status-seeking behaviour: standing in one or more peer gro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Transliteration

- List of Abbreviations

- Maps

- INTRODUCTION

- Part I THE USES OF IDENTITY IN GEORGIAN FOREIGN POLICY

- Part II THE REGIONAL CONTEXT

- Part III GEORGIA AND THE ‘WEST’

- Part IV GEORGIA AND THE GREAT POWERS

- AFTERWORD

- Bibliography

- Index

- Imprint

Citation styles for Georgia's Foreign Policy in the 21st Century

APA 6 Citation

[author missing]. (2022). Georgia’s Foreign Policy in the 21st Century (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3112964/georgias-foreign-policy-in-the-21st-century-challenges-for-a-small-state-pdf (Original work published 2022)

Chicago Citation

[author missing]. (2022) 2022. Georgia’s Foreign Policy in the 21st Century. 1st ed. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://www.perlego.com/book/3112964/georgias-foreign-policy-in-the-21st-century-challenges-for-a-small-state-pdf.

Harvard Citation

[author missing] (2022) Georgia’s Foreign Policy in the 21st Century. 1st edn. Bloomsbury Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3112964/georgias-foreign-policy-in-the-21st-century-challenges-for-a-small-state-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

[author missing]. Georgia’s Foreign Policy in the 21st Century. 1st ed. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.