This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

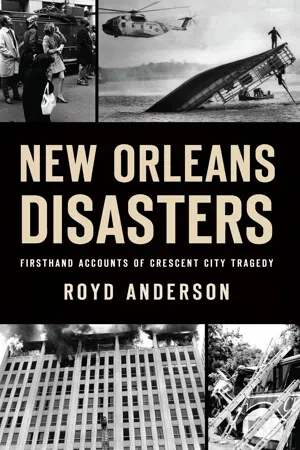

About This Book

With more than one thousand books on Hurricane Katrina, somehow not one work examines a collection of Crescent City calamity--until now. Here seven tragedies and their fallout are explored through gripping firsthand interviews, planting readers amid the chaos. Revisit the agony of the Luling ferry disaster, the horror of Pan Am Flight 759 slamming into a Kenner neighborhood and the Mother's Day bus crash on 610 that claimed twenty-two lives. Sift for answers in the unsolved fires of the Rault Center and the UpStairs Lounge. Investigate the Continental Grain elevator explosion and experience the terror of the Howard Johnson's sniper. Join author Royd Anderson on this harrowing journey through New Orleans tragedy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access New Orleans Disasters by Royd Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A SIGN FROM ABOVE?

It was partly cloudy and in the low seventies on the night of Monday, July 17, 1972. Father Joseph Breault made a supernatural discovery inside his Ramada Inn room at 2222 Tulane Avenue. The Pilgrim Virgin Statue was weeping! Through the evening and into the early morning, the relic sporadically shed tears over a period of four hours. During his time as the custodian of the visiting statue, this was the thirteenth and most prolonged time the padre had observed the miracle.

The Fatima statue crying. Illustration by Margaret Raslavich.

The remarkable Fatima cedar wood statue is one of two in the world, sculpted by José Thedim in 1947. Its appearance was ascertained through the explicit directions of Sister Lucia, who was one of the three shepherd children visited several times by Our Lady’s apparition at the Cova da Iria, near the village of Fatima in Portugal in 1917.

The Ramada Inn was located five blocks from the Central Business District (CBD). In less than a year after the Pilgrim Virgin Statue wept there, three major tragedies occurred in the CBD: the Rault Center fire (November 29, 1972), the Howard Johnson’s sniper (January 7, 1973) and the UpStairs Lounge fire (June 24, 1973). Incidentally, the author of this book was born during the week she wept, on Saturday, July 22, 1972.

2

THREE MAJOR TRAGEDIES IN THE CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT IN LESS THAN SIX MONTHS

THE RAULT CENTER FIRE (NOVEMBER 29, 1972)

New Orleans was strained during a disconcerting forty-five-day period in 1972.

On October 16, House Majority Leader Hale Boggs (D-LA) disappeared in Alaska and was later presumed dead. He was aboard a twin-engine Cessna 310, traveling from Anchorage to Juneau with Representative Nick Begich and his aide, Russell Brown. The plane, pilot Don Jonz and its passengers have not been located to this day. A young Bill Clinton assisted Boggs to the San Antonio airport for the first leg of the ill-fated trip.

Student protesters at Southern University had occupied the administration building on November 16 as part of a movement to restructure the university (the nation’s largest Black college at the time). Unarmed freshmen Leonard Brown and Denver Smith were shot and killed during a confrontation between students, the East Baton Rouge Parish sheriff’s deputies and state police. No lawman was fingered or charged with the shooting. This prompted a Black power memorial service and student boycott at Southern University in New Orleans. Most of the students didn’t want to return to classes, since the Baton Rouge campus remained closed.

The week of November 26 began with a tilt. A new state law enforced on January 1 banned gambling-type pinball machines, a feat that took over forty years to finally render. With 64,325 in attendance at Tulane Stadium, the Saints won only their second (and what would become their last) game of the season, defeating the Rams, 19–16. The Godfather was playing at the Airline and Algiers S. Drive In Theaters, while Deliverance was featured at the Saenger Orleans.

Mobile Oil Company geologist Michael MacKenzie has a story from this week that haunts him to this day. It occurred on the afternoon of Wednesday, November 29. He spoke of the incident from the back room office of his century-old Uptown home.

Hale Boggs. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

There’s the Downtown Howard Johnson’s hotel on Loyola Avenue, a block from the Rault building, and my wife Janet and I were having lunch in that hotel. When we were through lunch, we looked at each other and said, “Should we have another cup of coffee?” Which we did, and that took about fifteen more minutes. Then we walked outside the hotel onto Loyola Avenue, turned right, went about a block to the intersection of Loyola St. and Gravier St., and turned right on Gravier to get to the Rault Center. Janet was going to go up into the beauty parlor of the Rault Center and have her hair worked on. We were about twenty yards from the building when a window blew out in the front of the building, almost overhead. We stopped, because that gave us an idea that there was a fire in the building.

Because of the window explosion, the MacKenzies did not enter the Rault Center. They stayed for about fifteen to twenty minutes longer before leaving the area, and they heard about the horrific news on later news broadcasts.

The Rault Center, located at 1111 Gravier Street, was opened on September 8, 1967, as the first New Orleans high rise to incorporate office spaces with luxury apartments. It was conceived of and owned by Joseph M. Rault Jr., a successful oilman, real estate developer, attorney and community servant. Practically half of the sixteen-story-with-penthouse skyscraper was used as office space by Mobile Oil and the Rault Petroleum Corporation. Seven floors held apartments and suites. The fifteenth floor had several meeting rooms and a beauty salon. The top floor was occupied by the exclusive Lamplighter Club, which operated a restaurant. The penthouse area was used as a health club and spa, equipped with a rooftop sundeck and swimming pool.

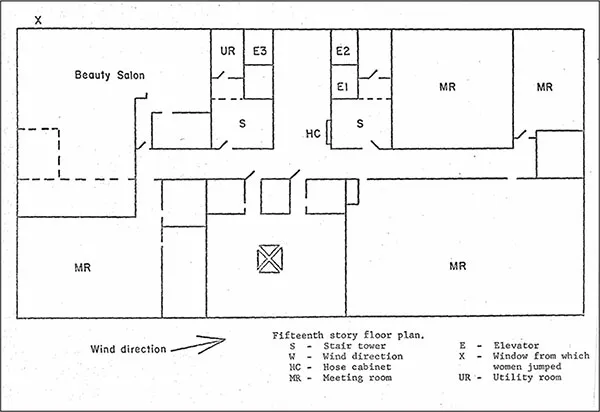

The mysterious fire began in the Ski Chalet Meeting Room on the fifteenth floor, located roughly in the middle of the building on the Gravier Street side. The room was paneled on three sides and had a suspended ceiling with one-by-twelve-inch pine boards furred out about half an inch from one-half-inch gypsum wall board. Separated by concrete uprights, the fourth wall was composed of plate-glass windows. The floor was carpeted with a rubber underlay. Benches were secured to three of the four walls. The foam rubber–padded seats were draped with steer hides. Two panel doors adorned the wall between the Ski Chalet Room and central hall, which were about three feet apart. There were one-by-twelve-inch boards around the entryway to the Ski Chalet Room.

Rault Center advertisement, October 22, 1967. Courtesy of William Lanxner.

The undetected fire burned for an extended period, eventually gathering enough heat to blow out the quarter-inch plate-glass windows. Upon seeing this from the street below, Michael MacKenzie, who worked in the building, also saw the first puff of smoke. The fire looked as though it was fueled by natural gas. The States-Item quoted him as saying, “Because of the intensity of the initial flame, it reminded me of a gas flare. If you’ve ever been to an oil field, you know what I mean.”

State Fire Marshal Raymond B. Oliver’s report stated that the blaze had spread from the Ski Chalet Room into the fifteenth-floor hallway and moved in two directions, tapering toward South Rampart Street and raging toward Loyola Avenue, where it reached the Lamplighter Beauty Salon, which was catty-corner from the Ski Chalet Room.

Inside the salon, Jannas McBeth, Wilma Williams, Natalie Smith, Norris Farley and Jacqueline Maillho heard the fire, saw smoke and rushed to a corner window. There was little to stifle or stop the fire that was spreading toward the women, since the door between the hallway and salon entrance was typically left open. Flanked by the asphyxiating smoke, McBeth broke the window with a shampoo chair.

Fifteenth-floor blueprint. Courtesy of the NFPA.

The idiom “which way the wind blows” is a metaphor for a course of events. In the case of the Rault Center fire, the wind was a villain. As a result of McBeth smashing out the window, the wind, blowing past that corner of the building, generated an area of low pressure, drawing the heat and smoke toward the women. A draft was also blowing in from the broken windows of the Ski Chalet Room, creating a high-pressure area on that side of the building. This also helped spread the fire in the interior toward the salon.

Six air miles away, Dr. Raquel Cortina, in her first year as an Assistant Professor of Applied Music and Opera at the University of New Orleans, looked out of her studio window in the newly constructed Performing Arts Center; the scary sight of the city skyline is still etched in her memory: “I saw these flames just flickering a little bit, and I still went and started working with my student and the pianist. Then, I turned around to go back to my desk, and I see these flames just growing and growing! It was just really, really bad.”

At 1:28 p.m., the New Orleans Fire Department (NOFD) got its first call. The switchboard lit up “like a Christmas tree,” according to the dispatcher. In a brief period, more than one hundred calls about the fire were received. The calls came from outside the Rault Center, and all said the flames were coming from the upper floors. The fire ascended the side of the building and went into the windows of the Lamplighter Club on the sixteenth floor.

Dr. Raquel Cortina beside the same UNO studio window that she peered through in 1972 to view the Rault Center Fire. Author’s collection.

The first fire engine arrived at the scene at 1:30 p.m. Upon seeing the enormity of the blaze, a second alarm was raised. Two minutes later, reports of people trapped in the building were received, and a third alarm was promptly called. Firemen went to the rooftop of the neighboring Saratoga Building’s garage at the rear of the Rault Center, and phone calls to the department said there were people trapped at the fifteenth-story rear window. The women were located by the fire brigade at 1:35 p.m. From the garage roof, they attempted the rescue with a fifty-five-foot-tall ladder, but it only reached to the thirteenth floor, two stories below the women. Many failed attempts were made with a rope gun to shoot a rope into the window where the women were trapped. Each try required the rope to be rewound, a slow process that took away precious minutes. Why did the New Orleans Fire Department have only one rope gun at such a disastrous scene?

A crowd of onlookers amassed on Common Street and the neutral ground on Loyola Avenue; many were on their lunch hour or were Christmas shopping. The squeaking of brakes, car horns, roaring mufflers and rattling suspension systems faded from the atmosphere as a police motorcycle patrol closed off traffic. The frantic ladies above waved handkerchiefs and shouted to the firemen and cops below, their cries suppressed by the raging firestorm. By then, fifteen minutes had passed, and time was running out.

The Rault Center burning. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

At the Lamplighter Club, a reward ceremony was taking place for employee Luis Suazo. Approximately 100 to 150 people were gathered there, including Joe Rault. Ironically, he was awarding Suazo one hundred dollars for discovering and extinguishing a fire that had been reported to the New Orleans Fire Department at 7:59 a.m. that morning. The fire had occurred on the sixteenth floor on the opposite side of the building. When Suazo discovered it, thick, black smoke was gushing out of a small room’s closed doorway. There were fires in two areas of the room. It makes one wonder about the probability of two fires in one day and the possibility of arson. The building tenants might have misjudged the pungent smell of smoke for recurring smoke stench from the morning fire, stalling early detection of the afternoon fire.

Ladder too short. Courtesy of The Times-Picayune.

When patrons of the Lamplighter Club saw flames out of the windows and many heard the sound of an explosion, they rushed to the nearest stairwell. One man, as he was running down the stairs, thought he heard a knocking sound at the fifteenth floor. Thinking this may have been a person trying to escape to the stairwell, he opened the door. He saw nothing but flames and shut the door. Evidently, the noise he heard was the expanding of the door in its metal frame. Warped by the heat, the door did not shut completely. Heat and smoke poured into the stairwell, and eight men were forced to make an alternate escape route by climbing a drainage pipe to the roof.

A few floors below the fire, a civilian rescue attempt was underway. Twenty-six-year-old William J. Allen, twenty-six-year-old Lloyd Caldwell, thirty-six-year-old Charles J. Michel Sr. and an unidentified man took the elevator to assist. Allen and Caldwell were New Orleans Public Service Inc. (NOPSI) employees who had just checked the building’s gas service after the morning fire. Michel was an elevator repairman who was working in the building. As they approached the floor that contained the fire, the unidentified man panicked. He stopped the elevator and got off several floors below the fire, while the remaining three good Samaritans continued the rescue mission. When the fifteenth-floor elevator doors opened, a burst of flames and ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1. A Sign From Above?

- 2. THree Major Tragedies In The Central Business District In Less Than Six Months

- 3. TWo Major Tragedies On The Mississippi In A Little Over A Year

- 4. A New Decade, Another Major Tragedy

- 5. The 1990s Almost Escaped A Major Tragedy But Couldn’T

- Bibliography

- About the Authort