![]()

Part I

Sites of Miscellaneity

![]()

Chapter 1

Science in Regent’s Park

The Colosseum

Bernard Lightman

On March 15, 1855, the Times (London) reported on a trial that had taken place at the court in Guildhall. A fifteen-year-old boy, Joseph Cleasby, had been charged with robbery by his employer. On the stand Cleasby admitted to breaking open a cashbox and stealing fifteen pounds. When he was asked how he spent the money he replied, “In going to different places of amusement at the West-end.” The examining official was skeptical. Had he spent all of the money in this way? Cleasby insisted that he had, replying, “I went to the Panopticon, the Great Globe, the Diorama, the Colosseum, and the Polytechnic during the day, and at night I went to the theatre.” Suspicious that Cleasby had also given some of his ill-gotten gains to companions, the court ordered him to be questioned further by the police.1 Cleasby’s story illustrates how much the world of science exhibitions appealed to London teenagers. In his testimony to the court Cleasby mentioned three science exhibitions: the Royal Panopticon (1854–1856), the Great Globe (1851–1861), and the Royal Polytechnic Institution (1838–1881). They were considered to be just as entertaining as the theater or a diorama. Even if Cleasby had fabricated the story to protect his friends, he must have thought it would be plausible to the court. The story was only believable if it was widely known that working-class teenagers found the temptations of science to be irresistible.

Shortly after Cleasby had supposedly paid his visits to West End sites of amusement, the Colosseum (1829–1864) was put up for sale and purchased by new owners who intended to integrate more science into its exhibits. Unlike the Polytechnic, the Panopticon, and the Great Globe, the Colosseum was not initially devoted to science. At first, it was known for its fine arts exhibitions. Scholars have paid it relatively little attention. There are only two detailed studies. In his Shows of London, Richard Altick devotes a chapter to the Colosseum, titled “A Panorama in a Pleasure Dome.”2 In this historical overview, Altick portrays the proprietors as struggling to establish an educational institution in the face of insurmountable pressure to offer pure entertainment.3 In his beautifully illustrated but rather short book on the Colosseum, Ralph Hyde focuses primarily on the early years. But this is a period when science played a minor role in its offerings.4 Historians of science have largely ignored the Colosseum, perhaps because its status as a science exhibition is not obvious. Indeed, some might argue it was not a science exhibition at all. Here I will contend that, by the middle of the century, the Colosseum should be placed alongside the other important science exhibitions of the period such as the Royal Polytechnic Institution, Wyld’s Globe, and the Panopticon. By considering these venues together, we can better understand how the varied spectacles offered by scientific display fascinated Victorian audiences.

The Colosseum was one of those protean institutions that changed its identity whenever a new proprietor took control. During the thirty-five years it was open for business, ownership changed hands at least five times, and three patterns emerge. First, the target audience for the exhibition slowly changed. At first, the Colosseum aimed to attract members of the nobility and gentry, but by the middle of the century it was also seeking to appeal to the middle class and artisans. Second, its thematic focus gradually moved from the fine arts to a combination of science and the arts. This would seem to suggest that the proprietors saw the inclusion of more science as the best strategy for attracting a broader public. Third, throughout its business life, the Colosseum offered its visitors a dizzying series of diverse exhibits. This is what makes it difficult to categorize. Before science became more prominent, the Colosseum was referred to in the periodical press as one of the “most luxurious places of resort,” an “amphitheatre of art and beauty,” and one of the “profitable places of amusement.”5 But the most widely used term to describe the Colosseum was “exhibition.” In 1827 the Times referred to it as a “public exhibition,” while in 1849 the Morning Chronicle designated it as one of the “magnificent metropolitan exhibitions.”6 The guidebook produced by the proprietors in 1829 also used the term “exhibition,” though it was an “original, singular, and unique exhibition.”7 An examination of the Colosseum helps us to think about the different types of scientific exhibitions and about their relationship to science museums.

Horner and the Early Years

When the Colosseum first opened its doors for private and public showings, in the middle of January 1829, the periodicals were wildly enthusiastic. The reporter for Pierce Egan’s Weekly Courier referred to the Colosseum as the eighth wonder of the world. There was “nothing like the Colosseum in the Metropolis” and when it was completely finished it would be “unequalled in the world.”8 A story in the Morning Chronicle was just as positive. The Colosseum was described there as a “singular, ingenious, and magnificent place of national amusement.”9 John Bull reported, “this stupendous and magnificent building is at length thrown open to the inspection of the public, and has astonished all who have visited it.”10 The primary feature in the Colosseum, a gigantic panorama of London, is what impressed visitors the most. The centrality of the panorama marked the Colosseum as a fine arts exhibition, and the high admission prices restricted the audience to the well-to-do.

But there was a lengthy and fascinating history predating the openings that had already cast a shadow on the Colosseum’s future. The man responsible for the idea of constructing an enormous panorama of London was Thomas Horner (1785–1844), a surveyor who devised a new method of drawing estate plans that he referred to as “panoramic chorometry.” Horner claimed that his plans were so accurate they could be transformed into bird’s-eye views of the estates he had depicted. In 1820 he began work on a series of sketches of London as seen from the summit of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Perched precariously in a small observatory cabin near the top of the cathedral, Horner produced a series of detailed sketches with the aid of a telescope. Rowland Stephenson, a wealthy landowner and banker, persuaded Horner to use the sketches to create a gigantic 360-degree panorama. Horner obtained four acres of land from the Crown on a ninety-nine-year lease in the southeast corner of the Regent’s Park. With Stephenson’s financial backing, construction of the Colosseum began in 1824 and was completed by 1826. The artist Edmund Thomas Parris was hired to direct a team of painters to transfer Horner’s sketches to a huge canvas. But completing the painting took much longer than Horner had planned.11 Delays meant increasing costs. In August 1827, the Times explained that the delay was due to the sheer size of the panorama. It was forty times larger than the panoramas to which London audiences were accustomed.12

Horner’s financial difficulties worsened at the end of 1828, when it was discovered that Stephenson had been embezzling funds from his bank. On December 29, 1828, the Times reported that a warrant had been issued for Stephenson’s arrest, and that he had suddenly disappeared.13 With Stephenson’s whereabouts unknown, Horner met with his friends on January 3, 1829, to explain the situation. Expensive supplies promised by Stephenson had never been delivered. The panorama could be completed in six weeks but sixty thousand pounds sterling were needed. Horner had decided to open the Colosseum to the public in its unfinished state so as to raise the needed capital. The mid-January opening of the Colosseum, despite the positive reviews, was an act of desperation. Although visitors poured into the building during the rest of January and throughout February, Horner’s situation was precarious.14 On March 15, Bell’s Life reported that the Colosseum had been “transferred by Mr. Horner to a Committee of highly respectable gentlemen for the benefit and advantage of all his creditors.” Horner was “going abroad.”15 Horner left Britain for the United States, never to return. In the meantime Stephenson had also fled to the United States. When he arrived in Savannah in March he was arrested and put in a debtors’ prison but later released since no extradition treaty existed between Britain and the United States.16

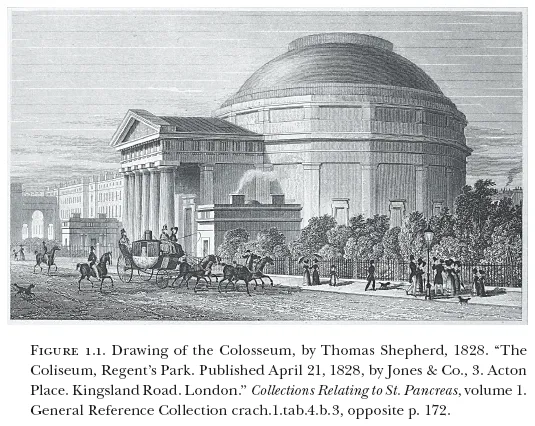

Hyde suggests that the association with the lurid scandal surrounding Stephenson actually helped to boost attendance when the Colosseum was first opened to the public.17 But according to the Mirror, in a set of articles published just after the opening, both the exterior and the interior were extremely impressive. Designed by the architect Decimus Burton, the Colosseum was a polygon of sixteen sides 130 feet in diameter and 110 feet in height (fig. 1.1). Its name was an allusion to its colossal dimensions rather than a claim that it resembled the Roman Colosseum. In fact, the Colosseum bore more of a resemblance to the Pantheon in Rome, due to its Greco-Doric portico.18 Inside, visitors would find a circular saloon to be used for the exhibition of paintings and other fine arts productions. Up a flight of stairs—or via a hydraulic ascending carriage, the first of its kind—visitors could view the panorama of London as seen from the top of St. Paul’s Cathedral. The Mirror reporter was astonished not just by the beauty of the gigantic painting but also by its accuracy. The Colosseum also contained a reading room, a library, conservatories, and a chamber created to resemble the inside of a Swiss cottage. In sum, the reporter asserted that the Colosseum was “one of the most gigantic enterprises for public gratification which it has ever been our lot to witness.”19

In the first few years, visitors to the Colosseum were nobles, gentry, and the well-to-do. During the summer of 1829 a long list of aristocratic visitors made their way to the new attraction, including the Duke of Sussex, the Dukes of Devonshire and Newcastle, Earls Egremont and Westmorland, the Marquis and Marchioness of Stafford, the Marchioness of Cleveland, the Marquis of Exeter, Earls Grosvenor and Harrowby, and Lords Berresford, Tullamore, Manvers, Deerhurst, Yarborough, and Wilton.20 Bell’s Life reported that when Parliament began to meet in May 1830, the Colosseum had become “a great point of attraction. For several days a great number of the Nobility and Gentry have visited the place in parties.”21 Only the wealthy could afford the admission fee. When the Colosseum first opened to the public in the middle of 1829, Bell’s Life noted, it was “crowded by fashionable visitors” who paid a sovereign for admission for four persons. Single tickets were not being sold.22

At some point later that year, the proprietors began to experiment with admission fees in order to make it possible for more visitors to see the panorama at a cheaper price. Announcing a “new arrangement of admissions,” viewing just the panorama now cost one shilling. Visitors paid three shillings to see the panorama and to enter the Saloon of Art, while entrance to the conservatories, fountain, and Swiss cottage was priced at two shillings.23 By April 1832 further changes had been made to the price structure. Admission to the entire interior of the building, including the panorama, now cost one shilling. Entrance to the exterior, which included the conservatories, fountain, a marine cavern, the Swiss cottage, alpine scenery, and waterfalls, was the same price.24 Several journals noted the impact of the new prices. The Morning Chronicle was pleased that the new admission prices would make it possible for “all who are not positively destitute” among the “middling and lower order” to visit the Colosseum.25 Bell’s Life reported an extraordinary increase in the number of visitors as a result of the reduction in admission. The number of visitors now averaged about one thousand daily. “We always regretted that the prices at first charged for admission,” the journal reporter wrote, “to this most wonderful collection of the works of art were so high as to place it beyond the reach of the great majority of the public.”26 In June 1833, the Literary Gazette expressed its pleasure in finding the Colosseum “crowded with visitors of every class, from high fashion to holyday-making tradespeople and artisans.”27

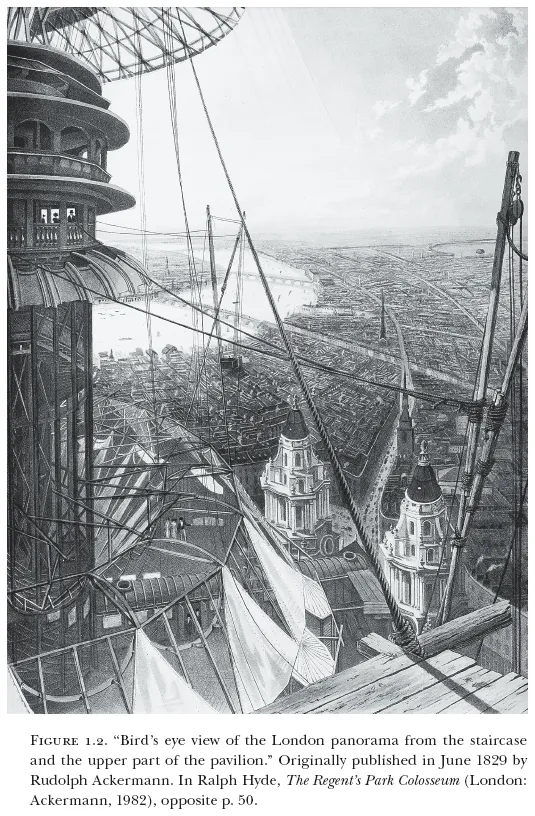

From the start, the Colosseum was intended to be a showcase for the fine arts, with the panorama of London as the chief focus, and when it first opened it was discussed by the Literary Gazette under the heading of “Fine Arts.”28 Similarly, the Morning Chronicle treated the Colosseum as offering a fine arts exhibition and lavished praise upon it since “we are friendly to the Fine Arts.”29 The fine arts were used by the Colosseum as a way to explore different ways of seeing. Periodicals inevitably dwelt on the panorama of London and the impact it had on the senses (fig. 1.2). To the Theatrical Observer, when viewing the panorama the “mind is lost in astonishment at the correctness and sublimity of the effect.” The spectator was filled with “wonder and delight.”30 Similarly, in a series of articles, the Morning Chronicle emphasized the reaction of “surprise” experienced by the visitor. “The whole effect” of the panorama was “surprising and delightful; emotions of lofty feeling arise on surveying the wide expanse.” The following year the Morning Chronicle again emphasized that the panorama was so “life-like” that the first glimpse of it brought “pleasure and surprise” to those who saw it.31 The Penny Magazine echoed these points. The spectator was “startled by the completeness of the illusion.” The vast size of the panorama was “calculated to impress the mind with a sense of surprise, not unmixed with those feelings which belong to the contemplation of any vast and mysterious object.”32 To the Morning Chronicle, the panorama of London was emblematic of what the Colosseum as a whole was intended to accomplish. A “magical palace,” the Colosseum was designed as a place where “all that dazzles the senses is combined to please and delight the visitor.”33

Although the fine arts were front and center in the Colosseum, there were some exhibits that were scientific in nature. In Europe there had long been a tradition of displaying objects from the worlds of science and the fine arts together in lavishly decorated cabinets. Early modern collectors displayed mathematical and optical instruments side by side with their paintings, sculptures, and carvings.34 Shortly after the Colosseum opened, Bell’s Life discussed the kaleidoscope that lit the tunnel from the conservatories to the Swiss cottage. Throwing a variety of colors on surrounding objects, the kaleidoscope was “one of the most magic and enchanting objects which optical science and creative fancy ever devised.”35 The emphasis on optical science in the Colosseum, which would be continued in later years, was in line with the exploration of ways of seeing through the fine arts.

The Colosseum proprietors incorporated more scientific features starting around the time that the Adelaide Gallery opened in 1832. Advertisements drew the attention of botanists to the conservatories, especially when a rare specimen had been obtained. In October 1832, the proprietors announced that a large American Aloe had come into bloom, producing more than four thousand flowers.36 Zoology was not ignored. In 1833 a new exhibit was added, titled the “African Glen.” An early example of a natural history “life group,” the African Glen consisted of a variety of stuffed birds, beasts, reptiles, and insects in positions as they might be seen in their native habitat. The Times noted that the exhibit contained some rare specimens rarely seen in Britain, in particular the tapir.37 Two years later the Times reported that the African Glen exhibit had been vastly improved through alterat...