![]()

1

An Unseen Force in the New South

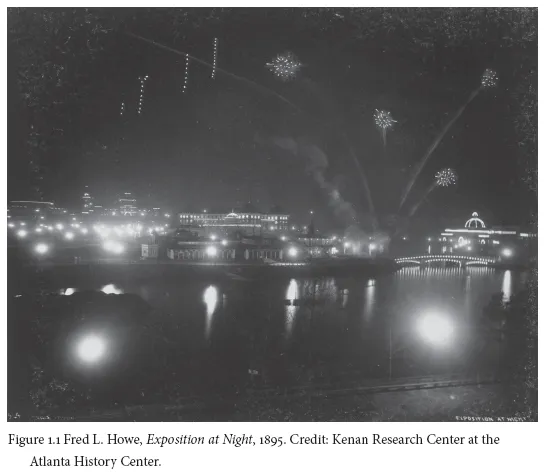

IN ANTICIPATION OF the upcoming festivities on an October evening at the 1895 Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition, a local reporter expressed exhilaration at the thought that “tonight the exposition grounds will be a blaze of glory.” Alongside flame-spewing volcano-like structures, the expo’s electric lights “dart[ed] back and forth among the buildings like fiery serpents. Everything will be weird in the peculiar glow.”1 The fair’s official guidebook likewise emphasized electric lighting at the fair, which offered as its most stunning feature an “electric fountain that glitters over beautiful Clara Meer like a rainbow of the night.”2 Even people with no direct stake in Atlanta’s reputation professed amazement. A writer for the Nation confessed that the Atlanta expo’s electrical display produced a “fine artistic effect . . . and the general effect is fairy-like.”3

Such scenes, and glowing descriptions of their electrical glory, were commonplace in fin-de-siècle America. World’s fairs, especially after the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, almost as a matter of course featured awe-inspiring electric light shows, electrically illuminated buildings and fairgrounds, and “electricity departments.” Yet more than simply standing as gaudy exhibitions of the latest innovations, electric lighting at late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century expositions signified white America’s racial, cultural, and technological supremacy. These demonstrations gave “Americans a feeling of participation in a national experience superior to all others, the fairs serving to establish America and Americans as special.”4

The Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition held to this pattern, calling on electricity to narrate in both symbolic and concrete terms the post-bellum South’s purported success story.5 Yet it was only one of Dixie’s world’s fairs. With displays of electrical prowess in cities such as Atlanta (1881, 1887), Louisville (1883–1887), and Nashville (1897), southerners announced their membership in the elite club of advanced societies. These expos furthermore declared that the “New South,” an agenda bent on modernizing the region through rapid urbanization and industrialization, was open for business. In Atlanta’s case, according to Henry Morrell Atkinson, the expo’s electrical department chairman, “electricity . . . will do its part in demonstrating the progress of the age and the latest improvements in the comforts and necessities of life. And this is what the success of an exposition consists in.”6

Electricity’s special role at the expo went beyond conspicuous display. For Atkinson, electric power was the “unseen force” that “put the throb of life into every section of the exposition grounds”; it powered the less obvious but crucially important elements of the fair as well. Aside from decorative purposes, electricity was responsible for “the patrol and alarm systems, supplying motive power, transportation by land and water,” and a host of other functions. But demonstrations of electricity’s uses far exceeded the limited scope of the exposition. According to Atkinson, electricity had helped turn Atlanta into the glowing, bustling New South capital. This unseen force “signalized and manifested in many ways the general gains and advances in governing conditions of everyday life . . . , in social welfare, [and] in industrial progress.” These lessons in southern advancement became possible through southerners’ cooperative efforts, with a “swiftness and accuracy of purpose which are undoubtedly proofs of genius in those” who had “harmoniously” made electric power a reality.7

Atkinson’s remarks about the significance of the “unseen force” are instructive in two primary ways. First, they point out that electricity was not simply an ornamental aspect of the exposition. It proved essential to seemingly mundane but indispensable operations at the fair and made modern life in a regional capital possible. His pitch is also telling in that, while it spoke to electricity’s seemingly underappreciated part in the making of Atlanta and its exposition, it contained a fundamental deception. As one historian writes about extravagant electrical shows at world’s fairs, “the entire scene was completely artificial, a simulacrum of an ideal world.”8 Atkinson’s version of electricity at the fair, and by extension in daily life in the broader New South, likewise presented a “simulacrum of an ideal world.” The depiction of electrification’s ascent as an abstract “unseen force,” as having proceeded swiftly and amiably, as having gained acceptance as a universally awe-inspiring, beautifying, progressive, and even magical force obscured as much as it illuminated.

The realities of electrification’s initial stages—from the early 1880s through the 1890s, when arc lights and trolleys first appeared on city streets—offer a different account. Electricity’s rise, and indeed the entire history of electrification, was far messier and more problematic than Atkinson and other southern boosters allowed. This was not a story in which a mystical wonderworker magically illuminated and powered the New South. Nature’s bounty—including increasingly voluminous streams of coal and water from the Appalachians—underwrote this supposedly unseen force. Neither was it one of easily won achievements, congenial cooperation, uniform popular acceptance, and an unfettered free market. It was, rather, a story of near-constant friction. Power company failures, conflicts between business leaders, and governmental interventions marked the electrical age’s beginnings.

Big business made the birth of electrification possible, but the process was neither smooth nor coherent. Despite inauspicious, modest, and fractured beginnings, the southern electric industry, even in a supposedly laggard Dixieland, was a full participant in the late nineteenth-century corporate consolidation craze, which saw electricity and the modern corporation emerge simultaneously.9 Fierce rivalries over market control within the chaotic and highly competitive world of modern capitalism characterized the dawn of the electrical age in the South, as in the rest of the United States. In this context romantic southern notions of gentlemanly cooperation and traditional decorum and honor would not do. Cold-blooded calculation reigned. Indeed Atkinson spoke not simply as a civic booster in 1895, but also as president of Atlanta’s near-monopoly electric lighting company with designs on overtaking both the lighting and streetcar business in the entire city.

The quest would not be easy. Electrification was a fragile process: not only were electrical systems technically frail, but social, cultural, and political realities threatened this emerging business as well.10 In the face of such precarious circumstances, the budding electric industry had to rely on the power of government to become viable and ultimately to stay in business. Exclusive contracts in the 1880s and 1890s and municipal legislation after the turn of the century proved necessary to support and then to cement the place of private-power companies in the early twentieth-century South. Prior to receiving public assistance, however, when limited to the nascent street lighting business, it appeared that electric power might have a difficult time even surviving its infancy.

Before electricity became the “unseen force” behind the modern city’s functions, it operated as the animating power behind the very-well-seen arc light. Millions of people likely saw electric lights for the first time at expositions, but the use of spectacular lighting as a lesson in civilizational advancement was not limited to world’s fairs. Electric arc lights debuted in American streets, just as in expositions, as examples of “technical monumentalism.” Scholars tend to agree that the arc lamp, which produced a brilliant “arc” of light in the open space between two carbon electrodes heated by electric current, served as a shining emblem of progress, not primarily as a tool for improving the functionality or safety of public spaces. Only with the emergence of so-called Great White Ways in city centers across the United States did these lights come to serve the utilitarian function of stoking commercial activity.11 Atlanta’s early experience with electrification in part confirmed that position. Yet it also demonstrated that the people supporting the establishment of an electric illumination system called on this dazzling symbol for an explicitly utilitarian function. Arc lights contributed to the making of the New South.

People like Atlanta Constitution editor Henry Grady, widely considered the New South agenda’s most important spokesman, believed Dixie’s regeneration was urgent. At least since the early nineteenth century but certainly after Reconstruction, many prominent southerners claimed that the white South’s devotion to slavery and disdain for urbanization and industrialization left the region on the margins of American abundance. The region had no shortage of natural wealth; what it lacked, many believed, were the mechanisms to convert raw materials into locally distributed and widely shared profits. The benefits of the South’s natural bounty flowed instead to the more developed North. Dixie witnessed the results of that flawed system most acutely in the 1860s, when the Confederacy suffered devastating military losses to the industrially superior Union, and after the war when it watched its economy languish while the North’s boomed.12

Especially against a burdensome backdrop of defeat, poverty, and underdevelopment—a history not of abundance but of scarcity—southern civic boosters advocated for a “New South” of growing cities and factories. Leading entrepreneurs thus installed ornamental electric lights in streets, shops, places of entertainment, and world’s fairs to serve as both evidence of and the basis for the rapid expansion of their newly urbanizing-industrializing society. The Atlanta City Council asserted as much in 1895. Despite a devastating situation in the 1860s, it claimed, the city could now call itself “one of the best illuminated in the Union.” As such, and in concert with street railways, a mild climate, and other advantages, Atlanta offered potential investors “everything that is favorable to successful manufacturing.”13 So alluring was the promise of this new technology that even small southern towns embraced the hope that electric lights would spark growth. “The next thing” in its development, an Alabama newspaper predicted in 1892, “will be electric lights, then will come factories, etc. Let the good things come.” Similarly, a North Carolina man joked that “electric lights, etc. are booming here; N.Y. and Boston will be mere suburbs of Chapel Hill, N.C. soon!”14

Pronouncements about the utility of electric lighting were not simply the fantasies of Dixie’s self-aggrandizing cities or hopeful towns. The National Electric Light Association (NELA), the US electric industry’s trade organization founded in 1885, explicitly encouraged cities to embrace electricity’s role as both a spectacle and tool for growth. “A city is judged by impressions,” explained a NELA pamphlet. “It may have every natural advantage that a business man may desire. Yet, if it be unattractive, dirty and gloomy, its development will be slow.” Decorative street lighting, NELA concluded, played a fundamental role in urban-industrial development.15

Even if boosters and trade associations emphasized the functional purposes of electric lighting as much as its symbolic uses, the arc light’s debut in the late 1870s nevertheless inspired in southern residents, or at least in booster-journalists, a sense of awe. Many southerners likely witnessed the arc lamp’s sublime power for the first time in autumn 1879 when W.W. Cole’s New York and New Orleans Circus, Museum, Menagerie, and Congress of Living Wonders toured cities such as Atlanta, Greenville, Montgomery, Nashville, and Pensacola.16 Although Cole’s traveling circus promised an array of expected attractions—freak shows, performing animals, exotic enticements—the Atlanta press seemed most thrilled by the news that the show would feature arc lights. Advertisements in the city’s papers peddled the show as the “first exhibition in Atlanta of the wonderful electric light,” which would make “dense night as brilliant as a southern sun.”17 The Sunny South, an Atlanta-based literary newspaper, urged readers to attend the circus because it “opens with the wonderful Electric Light which we are all anxious to see.”18 The Atlanta Constitution billed Cole’s circus and its technological marvels as phenomena for which even Biblical wisdom could not adequately account: “The Electric Light Show: Something New under the Sun.”19

When Cole’s troop arrived in Atlanta in early November, some three thousand to four thousand people attended daytime activities to gawk at a pair of giants, a trapeze act, a clown routine, and a lion taming exhibition. As anticipated, however, the dazzling demonstration of electric lights stood out as the big hit of Cole’s stop in Atlanta. The Constitution reported that “the night performance was even better, if possible, than that of the afternoon, the wonderful electric light being seen to better advantage, and the crowd on hand larger by a thousand or two than in the afternoon.”20

A circus-going populace, or favorable press coverage, though, did not necessarily signify a widespread desire for the creation of an electrically illuminated city. Nor did it foretell the electric lamp’s ultimate triumph. In fact electric lighting suffered through a series of false starts, as well as a lack of popular enthusiasm, in the years following Cole’s visit. It took the intervention of municipal government, which finally came to believe that lights would help bring the city more investment capital and tax revenue, to establish this business as a permanent fixture in the urban landscape.

Nevertheless large southern cities were early (potential) adopters of the arc light. The South’s largest city, New Orleans, had already negotiated the installation of dozens of arc lamps by 1882 when a five-mile stretch of riverfront glowed under electric lights.21 Atlanta’s boosters believed that if the arc lamp illuminated their streets, their town would stand out as a progressive metropolis that might soon surpass New Orleans in national prestige and regional importance.22 Atlantans started serious discussions about bringing this technology to their streets following the International Cotton Exposition of 1881, whose purpose was to announce Atlanta as the leading New South city.23 The fair’s inaugural ball boasted “blazing electric lights, whose rays, as bright as polished silver, yet as soft as the mellowest moon light, created a scene as enchanting as from fairy land.”24 The fair’s organizers wanted to extend that scene to the streets and feared that, as NELA later warned, their city might not meet its billing as the New South’s core if it failed to quickly adopt electric lamps.

To accomplish this goal, Atlanta businessmen Jacob and Aaron Haas welcomed representatives of Cleveland’s Brush Electric Company, which dominated the American arc light equipment manufacturing business through the 1880s, to negotiate the establishment of an electric light company. The two parties agreed in principle to a deal in the summer of 1882, provisionally forming the Brush Electric Light and Power Company of Atlanta, with a proposed capitalization of $50,000. For the Haas brothers, the arc light’s sheer brilliance alone would bring further investment and handsome profits inevitably and quickly to Atlanta. In an interview with a reporter, Jacob Haas asserted that the “pure radiance” of electric lighting would soon shine on “every street in Atlanta” and eventually supplant the “sickly glare of gas in our shops, offices and drawing rooms.” Despite the democratic vision of illuminating every location in the city—and without an officially organized company or a contract for street lights—Haas and his brother secured lighting subscriptions solely from elite enterprises in the central business district. Chief among these were the posh Kimball House and Markham House hotels. Located near Union Railroad Station in the western portion of downtown, Kimball House and Markham House provided lavish accommodations for Atlanta’s well-to-do visitors and bachelors and served as a meeting place for business and political leaders.25 In the short term the arc lamp would brighten only the burgeoning New South’s most exclusive spaces.

Unfortunately for the Haas brothers, the electric light’s arrival was several years away and its rival...