![]()

1

The Golden Era

Perhaps, in time, an invention will be perfected that will throw the words spoken directly under the screen as well as being spoken at the same time.

—Emil Ladner, “Silent Talkies,” 1931

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, teachers dreamed of using innovative media that could enrich the education of deaf children. For decades they had experimented with combining pictures and words in their classroom instruction. In 1870, for example, James H. Logan, a deaf teacher at the Illinois Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, noted the usefulness of adjunct aids to improve learning. “Pictures,” he wrote, “besides the pleasure they give, act as definers of the text, and convey far more correct ideas than could be gained from the words alone.”1 Long before motion picture films arrived, he recommended the use of an “illustrative apparatus,” such as the stereoscope, stereopticon, or magic lantern slides for enhancing learning and entertainment through the combined use of pictures and text. “There is no good reason why every institution should not be provided with a good library and some illustrative apparatus,” he wrote from Jacksonville. “All the pupils, even the youngest, may be made to comprehend, but in different degrees, such things as they serve to illustrate. … The expense should be considered no objection at all. … The system of deaf-mute education must keep pace with that for the hearing and speaking …”2

THE FILM INDUSTRY BEGINS

It is fitting that the history of the entertainment and educational film experiences of deaf people includes the work of a deaf inventor, Thomas Alva Edison, who announced at his laboratory in October 1888 his plan to invent “an instrument which does for the Eye what the phonograph does for the Ear.”3 Edison’s intention was to record and reproduce things in motion. The motion picture films he first developed were not meant to be primarily educational.

Edison, who has been described as America’s greatest inventor, fostered a vision at his West Orange, New Jersey, laboratory to develop the motion picture to help “liberate the creative spirit by crystallizing and applying a teamwork approach to research and development.”4 The technology he developed, however, ushered in a revolution that provided a roller coaster of emotion for deaf people over the decades to follow.

Born on February 11, 1847, in Milan, Ohio, Edison grew up in Port Huron, Michigan. He only attended school for a few months and was subsequently tutored by his mother. Edison credited his deafness with helping him to concentrate on his experiments.5 He went on to accumulate 2,332 patents, leading Joseph Henry, president of the National Academy of Sciences, to describe him as “the most ingenious inventor in this country … or in any other.”6 His first motion picture apparatus, developed with the assistance of his employee, the photographer “William K. L. Dickson, featured a series of small photographs mounted on a cylinder not unlike that of his [early] phonograph. The images were viewed through a microscope attached to the rotation cylinder.”7 Edison focused on the electromechanical design while Dickson worked on the photographic and optical development and deserves much of the credit for the invention.8 In particular, Dickson was given the task of working on the process of moving film through the camera and propelling the image through a machine to view the picture—the Kinetoscope—the forerunner of the motion picture film projector.9

The film was obtained and codeveloped through collaboration with American inventor and manufacturer George Eastman of the Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, New York. After more work, patent applications were made in 1891 for a motion picture camera called a Kinetograph.

During the winter of 1892, Edison’s team constructed the world’s first motion picture studio. Nicknamed “Black Maria,” it was the location for the filming of Fred Ott in The Sneeze (1894), a boxing match between James Corbett and Peter Courtney, and Serpentine Dance (1894) starring Annabelle Whitford. Edison’s team also made documentary chronicles of real life, such as New Brooklyn to New York via the Brooklyn Bridge (1899).10

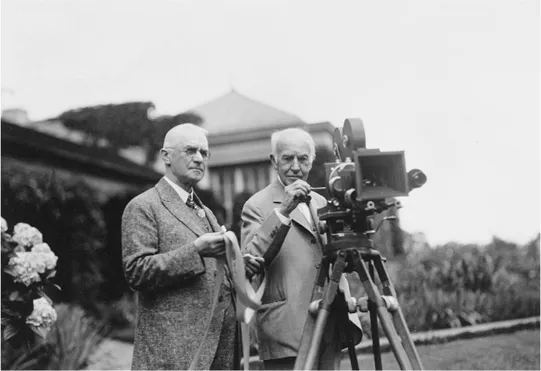

George Eastman (left) and Thomas Edison with a motion picture camera at Eastman’s house in 1928 in Rochester, New York, where a demonstration of the new Kodacolor film was being held. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On April 14, 1894, the world’s first commercial demonstration of Edison’s Kinetoscope took place at an arcade on Broadway in New York City. Within months, Kinetoscope or “peephole” parlors, also known as “nickelodeons,” opened in cities throughout the United States and Europe, including San Francisco, Atlantic City, and London.

Then, in 1895, two Frenchmen took advantage of Edison’s failure to patent his peephole machine in Europe. Louis and Auguste Lumière began to manufacture the Cinematographe, a more portable camera that projected moving pictures onto a screen. Their initial productions were realistic depictions of scenes from daily life and proved to be popular. As the collaboration between Edison and Eastman moved ahead, Étienne-Jules Marey’s work with roll film in France further enhanced the development of motion picture entertainment. The Lumière brothers closed their business in 1905, but other competitors such as the Biograph Company and Georges Méliès’s Star Film Company entered the field.11

Meanwhile, the deaf artist and photographer Theophilus Hope d’Estrella was creatively pursuing the use of still pictures. Known affectionately by students at the California School for the Deaf as the “Magic Lantern Man,” d’Estrella used lantern slides, glass-plate positive transparencies that were either black-and-white or hand-colored with transparent oils, and projected the images onto a screen using the stereopticon. The first Magic Lantern Exhibition held at the California School for the Deaf occurred in February 1888, and Berkeley citizens were invited to attend. “In the following weeks,” wrote d’Estrella’s biographer, Mildred Albronda, “the children applauded the blood-and-thunder images of great battles of the American Revolution and of the Civil War on land and sea. … Some of the slides produced the effect of motion which was accomplished by a special arrangement in the machine.”12 Before long, d’Estrella was presenting thirty to forty lantern-slide lectures per year to the deaf children.

As early as 1903, however, fascination with the lantern-slide magic was replaced by interest in the new moving pictures, and by 1910 the California School for the Deaf purchased motion picture equipment and was showing two or three movies a month. D’Estrella himself envisioned that the motion picture film would bring widespread changes in people’s use of leisure and in their perceptions about leisure time. Other schools serving deaf children soon followed. In Arkansas, the school’s baseball team raised funds to purchase a moving picture projector in 1912 by playing a game with the employees of the State Hospital for Nervous Diseases. Superintendent Isaac B. Gardner saw “wonderful educational value” in motion picture films for deaf pupils.13

The Edison Manufacturing Company sent crews around the world to capture unusual sights and events and began to produce more complexly plotted films. In December 1903, the company released Edwin S. Porter’s popular hit, The Great Train Robbery, which had location shots filmed near Edison’s laboratory in New Jersey. Many subsequent entertainment films were produced at Edison’s studios in Manhattan (1901–1907) and the Bronx (after 1907). Around the same time, other movie studios began competing with Edison. Eventually these studios moved many of their operations to Hollywood, California, and soon came to dominate the industry.

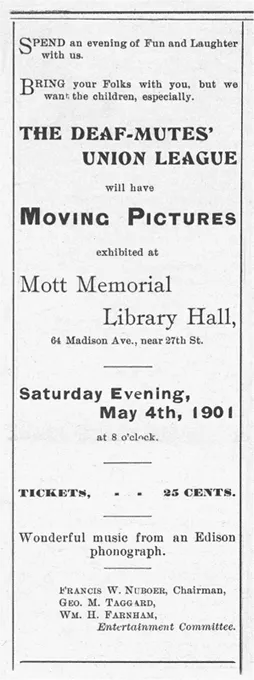

By the turn of the century, deaf people were enjoying the “moving pictures” at social gatherings. Some with partial hearing also appreciated the accompanying music played on Edison phonographs. This advertisement was for The Deaf-Mutes’ Union League Club gathering on May 4, 1901, in New York City. Deaf Mutes Journal, April 18, 1904. P. 2. Image courtesy of the Gallaudet University Archives.

In addition to Edison’s studio making close to 1,200 films, in 1908 he started the Motion Picture Patents Company, a conglomerate of nine major film studios. Four years later, he introduced his “Home Producing Kinetoscope,” one of the first home projection systems.

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, silent films became a popular attraction for both deaf and hearing people. With their visually effective quality and the use of body language and facial expressions, the silents presented an enjoyable medium for entertainment in the theaters. In addition, deaf actors were able to find employment, and schools serving deaf children saw the growing potential of motion picture film for education. In 1915, for example, the New Jersey School for the Deaf showed weekly films on topics such as nature study and bookmaking, and at least a dozen other schools owned projectors.14 “Our motion picture program becomes more extensive and important from year to year,” reported the Indiana School for the Deaf in 1929. “We are finding new ways to coordinate the motion pictures with our school program.”15 This school secured newsreels and longer plays from local exchanges, and educational films from Indiana University. The films were well received by the children and became part of the curriculum of the school day, whereas longer entertainment films were shown outside of school hours. The school reported that the educational films became “the basis of much of our composition, Geography, History and Current Topics, and the pupils followed up by requesting such items as wall maps in order to look up the locations of countries mentioned in the films.”16

In his book Hollywood Speaks: Deafness and the Film Entertainment Industry, John “Stan” S. Schuchman described how the silent film era “inadvertently” included deaf people who participated as equal members of an audience, as beneficiaries at schools, and as actors on the screen.17 He referred to this period in the cultural history of the American Deaf community as the “Golden Era.” Previously, sign language could only be expressed in static form. Now, movies were becoming a cultural product for deaf people. According to Schuchman, deaf audiences especially appreciated the silent films for the action and the expert use of facial and body expressions by many actors and actresses. Silent films depended little on the use of words in telling a story and provided a new tool for those who used sign language. “This explains the success of Charlie Chaplin,” Schuchman wrote, “who conveyed whole sentences with the twitch of an eyebrow.”18 Chaplin’s film subtitles were few and short.

PRESERVATION OF SIGN LANGUAGE

The age of silent films happened at the same time as influential people were campaigning against sign language in the United States,19 and films also were used as a form of social resistance during this period in history. Since the late nineteenth century, there were efforts to ban the use of sign language in American schools. Advocates of oralism emphasized the use of speech, speechreading, and residual hearing for educating deaf children, and they demeaned communication through sign language. Deaf people unable to teach speech were losing their positions in the schools, and the Deaf community, perceiving this as an attack on their linguistic rights, fought bitterly against the suppression of their visual language. They sought to preserve sign language through the use of motion picture technology. Between 1913 and 1920, the NAD collected funds to produce a series of 35 mm films on which were recorded poetry, lectures, memories, and stories in American Sign Language...