![]()

CHAPTER 1

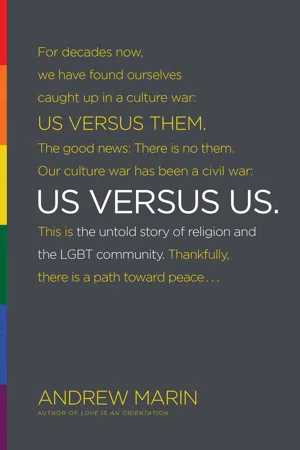

THERE IS NO THEY

86% of LGBTs were raised in a faith community from the ages of 0 to 18

I am who I am today and believe what I believe today because of the best of what [my church] taught me!

Kevin, a 52-year-old gay man, raised in an evangelical church

RAISED IN A RELIGIOUS COMMUNITY

- 75%: General American population

- 86%: LGBT

Data on general population from National Study of Youth and Religion, 2008

“From my earliest memories I remember my parents always dressing me up nicely and taking me to church every Sunday.” Carl, a 26-year-old gay man living in Chicago, Illinois, represents the overwhelming percentage of LGBT respondents who were raised in a religious community. “They loved that place. I never really minded it until I understood what ‘gay’ meant —in myself and in the church. Then it got all super intense and confusing, and I felt my churchgoing experience drifted away from what I understood a faith in God was supposed to mean. So no, I wouldn’t go back now. But I sure can’t deny how it implanted faith in me. Sometimes I think it’s like a virus I can’t shake.”

Seemingly everywhere I turned during my decade living in Boystown, I met another LGBT person raised in a religious community. But in the back of my mind I was skeptical. Did I somehow socially gravitate toward LGBT people raised in religious communities? Was I just hearing what I wanted to hear? Was I hypersensitive to LGBT people with religious backgrounds because of my own religious upbringing? I had no idea.

Because of these persisting doubts I defaulted to my normal way of resolving such problems: I blatantly asked the same question of everyone I came in contact with. Wherever I went, whomever I was talking to, I would not-so-subtly slip into the conversation, “So, were you raised in a religious community or not?” As Lauryn Hill states, if you’re looking for the answers, you’ve got to ask the questions.[1]

Whenever someone responded, I would pull out my trusty old on-the-go PalmPilot and tally the response. This process was, of course, completely unscientific. But based on the overwhelming “yes” responses, for the first time I realized I was indeed hearing my neighborhood’s stories correctly, regardless of what random person I happened to ask.

As I mentioned earlier, I tried and failed to find published data about the impact of childhood religion on LGBT persons. This revealed quite a conspicuous gap in the literature, because if national percentages were anything close to my informal neighborhood straw poll, the childhood faith of so many gay people would directly impact the dynamics of the budding culture war between the church and the LGBT community —which at that point emphasized theological and political differences without considering both communities’ actual backstories.

Around this time, Massachusetts became the first state to legalize same-sex marriage. The intense religious reaction to this legislation centered around a growing suspicion of a “gay agenda.” Logically I thought one or the other community would quickly turn their focus to LGBT religious experiences, if for no other reason than to raise the stakes by introducing God into the debate. But that never happened. And now, over a decade later, religion itself is at the center of the culture war —ground to be fought over, won, and owned by one side or the other.

Is 86 Percent Correct?

About 75 percent of Americans are raised in a religious community from ages 0 to 18.[2] Our research shows that the percentage of LGBT people raised in a religious community is 11 points higher than the percentage for average Americans. Although this total is larger than even I expected, I was glad to finally have the hard data to back up my anecdotal evidence.

Beyond the initial shock of the finding, it validates the lives and experiences of LGBT people I know who feel so alone in their faith journeys. It offers that same validation to the many other LGBT people whose journeys with faith have been met by deaf ears and unresponsive hearts. It reassures all those LGBT people with religious experiences and longings that they are not crazy. And most importantly, this 86 percent result brings a new social starting point to the LGBT-religion conversation. Carl, who had observed the same tendency among his gay friends that I had among mine, summed up the matter well: “It’s strange, right? I don’t get it but I’m sure with so many of us being raised in the church that it’s got to say something about the odd intertwining of our [LGBT and religious] communities’ paths.”

When the analysis showed an 86 percent result, I started double- and triple-checking the data. There are three main factors that could skew the findings upward: question bias, question confusion, and collection procedure. I began my search in the most obvious of places, survey question #31: “Were you raised in a specific religion?”

The scrutiny of this question begins and ends with the definition of “raised in.” Even the slightest of confusions could quickly lead to an inaccurate result. The survey defines the term in the introduction (in both print and online versions), and our research assistants read the definition out loud during the process of gaining participant consent:

This definition makes very clear that “raised in” can only be understood as long-standing, committed attendance. It rules out those who might have only regularly attended in spurts throughout their youth. Thus I’m quite confident the results are not affected by question confusion or bias.

Second, maybe the 86 percent was skewed by where and how we gathered participants? Another valid concern, yet our collection procedures followed the most rigorous standards for generalizable results.[4]

Third, because our research study focuses on religion, perhaps LGBT people with faith backgrounds self-selected while those from secular backgrounds were more likely to opt out? I am aware that our topic has a greater propensity to attract LGBT people drawn toward discussions of religion. But being drawn to religious discussions doesn’t require a formal religious background. In my experience, both religious and secular LGBTs consistently demonstrate an interest in religion, if for no other reason than to promote or defend their particular beliefs.[5]

In order to mitigate against self-selection, our research team intentionally did not partner with religious or faith-based LGBT organizations or events to garner participants. Nor did we partner with LGBT outlets who had overt connections to religious communities. Our participants were gathered in-person and online through partnerships with nonreligious entities: university groups, community centers, LGBT-rights organizations, nonprofits, HIV/AIDS groups and clinics, gay pride parades, the Gay Games, LGBT-specific neighborhoods, and online LGBT activist communities.[6]

Because these initial measures were in place prior to any collection of data, and because we double-checked the collection procedure after the fact, my very real anxiety about the validity of our findings was eased. Yet my sense of responsibility for what we had learned only increased.

The Burden of Responsibility

The 86 percent of LGBT participants raised in a religious community stretched over fifty-four denominations housed within eight religions.[7] Perhaps more surprisingly than even the high percentage of those raised with religion, over three-fourths were raised in theologically conservative religious communities. This secondary finding suggests that both extremes of the culture war literally grew up together; these two traditionally opposed populations —the conservative church and the LGBT community —are intimately connected to one another. An overwhelming percentage of the LGBT community spent their youth being taught, spiritually formed, and discipled in conservative religious circles.

This fact flies in the face of the dominant cultural narrative, which casts the parties to this conversation as opposing forces. In reality, the culture war has always been a civil war: us versus us.

Not surprisingly, the most common religious affiliations reported by respondents are consistent with the general American population.[8] Interestingly though, the denominations with the most influence on our LGBT participants as youth have also produced some of the most outspoken culture warriors against LGBT issues.

TOP THREE RELIGIOUS AFFILIATIONS LGBTS ARE RAISED IN

- 19%: Catholic

- 17%: Evangelical nondenominational

- 9%: Baptist

Kevin, a 52-year-old gay man living in South Dakota, was raised in an evangelical church. He said,

An important building block to any sustained relational healing is humility. A humble admission of responsibility in spiritual development will go a long way. Just ask Leon, a 25-year-old gay man living in Lynchburg, Virginia:

For every critique, however, there is something to celebrate. Sarah, a 21-year-old lesbian living in a small town in Wisconsin, continues to attend the evangelical church she was raised in.

The experiences of these three participants illustrate the complexity of the disconnect between religious communities and LGBT people. Even in measured generalizable themes, no two experiences are exactly the same or in need of the same solution. This is what makes it so difficult to pinpoint where to start a process of reconciliation. I have been in the thick of this conversation for years and have learned there’s a huge difference between engaging extremists (such as anything to do with Westboro Baptist Church) and authentic, committed engagement of those on the other side of the conversation (for example, the careful research of Dr. Warren Throckmorton).[9]

Faith and sexuality are both extremely nuanced and tender constructs; they demand to be handled with care, intentionality, and humility. Yet faith and sexuality alike have been stripped bare by the easily quotable but carelessly considered conclusions of a culture war being fought in the Internet age. Sam, a 28-year-old gay man living in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, holds a (sadly) unpopular view about how conversations about faith and sexuality should be conducted: