![]()

1

What is the brain?

In this chapter you will learn:

• how the human brain evolved

• the elements of the basic brain

• how the thalamus and the limbic system work

• the function of the cerebrum.

What makes human beings special? People have put forward any number of answers to that question. They have suggested that it is our ability to tell stories, to work together, to store information, to laugh, to imagine, to use language, to learn or to solve problems. It has even been suggested that we are distinctive because we are not really distinctive: we don’t have specialized horns, teeth, other natural weapons or the ability to run fast, and although we can do a lot of physical things, there are almost always other animals that can do them better. So because we are not particularly specialized in terms of our physical abilities or attributes, we have to work out different ways of doing what we need to do.

Any or all of these may be true. But underlying them all is the one thing which makes it all possible: the very special brain that human beings have evolved, and the way that it allows us to interact with our worlds – our physical worlds, our social worlds and our imaginary worlds. That brain is something very special, and it is what allows human beings to be what we are.

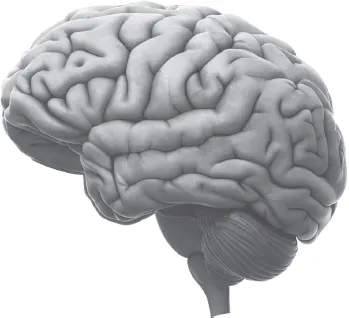

Figure 1.1 The human brain

Our brains allow us to see things and make sense of what we are doing. They allow us to take action: to move purposefully and do things when we need to or want to. They allow us to hear: to interpret vibrations in the air, to identify where they are coming from, and to identify their likely cause. They do the same for all of our other senses, including the sense receptors we have inside our bodies, which tell us what our muscles and joints are doing. Our brains make it possible for us to locate ourselves in the material world: to receive information from it, and to act within it.

But they do much more than that. Our brains also allow us to remember things – and in more than one way. They store conscious memories, like PIN numbers and addresses, but they also allow us to remember things that happened in the past, and even allow us to remember to do things in the future (most of the time!). They allow us to store skills, so that we can perform actions or cognitions smoothly and without consciously thinking about the steps involved; and they store patterns and meanings, so that we can make sense of new things that we encounter. They even allow us to imagine things that might happen in the future – or things that might never happen.

As social animals, it is important that we are able to recognize people, and it is our brains that allow us to recognize faces and bodies, and to distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar individuals. Our brains also make it possible for us to develop the attachments and relationships that are the basics of social living and to communicate with other people, using words, signs or symbols. At a more abstract level, our brains also make it possible for us to deal with the ‘three Rs’ – reading, writing and arithmetic, each of which involves distinct areas of the brain. But being human is more than just having mental skills of this kind: it is our ability to empathize with others which really makes us human, and our brains also provide us with the mechanisms for self-knowledge, identification and empathy.

We have emotions, too, and these are only possible because of how our brains have evolved. We feel anger, fear, happiness and disgust, we feel pleasure and pain, and we respond to rewards. We have times when we are alert and agitated, times when we are relaxed or experiencing states like mindfulness, and times when we are asleep. These states of consciousness are part of how our brains work. And, as human beings living modern lives, we also make decisions. The human brain is able to cope with decisions at various levels, ranging from deciding to sip a coffee to deciding to buy a house. The brain is an amazing structure, and in this book we will be exploring all these aspects of how it works.

How did the brain begin?

How did our brains become so complex? Back in evolutionary history, the first animals didn’t have brains at all. They were simple, one-celled organisms, a bit like the amoebae of today, which float in their liquid environment and absorb particles of food as they come across them. As more complex animals developed, one of their advantages was that they became able to detect nearby sources of food. They began to develop specialized cells that could identify the chemical changes in their environment produced by nearby food; and other cells that would help to propel their bodies towards it. They also developed a central linking system, which allowed them to use the information they were receiving and direct their movement accordingly. That central linking system acted as a co-ordinator between the incoming information and the resulting action.

And that was the beginning of it all. The first nervous systems were a simple, ladder-like network of fibres through the body, linked to a simple tube – which we call the neural tube. There’s something similar in the bodies of modern-day planaria, or flatworms. It’s basic, but we know it works because they still survive today. As animals became more complex, so did the structure of the nervous system. The front end of the neural tube began to become enlarged: it was the co-ordination centre which received information from the detectors that identified possible food, or light, or other information like vibrations, which implied that something large was nearby. Those detectors eventually became the sense organs, and the enlarged front part of the neural tube became the brain. The rest of the tube, which passed along the body, became the spinal cord, and the cells that passed information to and from it became the somatic (bodily) nerves. But even though it became so much more elaborate, it was, and still is, a kind of tube. It just has many more knobbly bits on the end than a flatworm has.

By the time of the dinosaurs, animals had become much more complex. That swelling at the front end of the neural tube had become a brain – not a very big one but one with different parts, which allowed it to co-ordinate the various bodily mechanisms needed to keep the animal alive, such as respiration, digestion and heartbeat. The brain also received information from the senses, which had become much more sophisticated, with their own separate organs and nerves and their own specialized parts of the brain. Movement and balance, too, had become vitally important functions, and a large part of the brain had developed to deal with these. And even a type of memory, although less complex than the memory we use, had begun to evolve. The dinosaur brain was tiny by comparison with our modern human brain, but, as palaeontology shows, it worked, and it worked very well. Dinosaurs dominated the land for many millions of years, and their descendants, the birds, are still with us today.

The same brain developments applied to other animals, like fish, amphibians and reptiles. Their adaptation to different ecosystems and food sources led them to evolve into all sorts of different creatures. Some of those ecosystems encouraged them to develop a highly sophisticated sense of smell, so the part of the brain dealing with smell became enlarged. Others required acute vision, which meant that the part of the brain dealing with vision became enlarged. Some animals developed an acute sensitivity to vibrations in the air, leading to an enlarged brain centre for hearing, and so on. As animals evolved to deal with their environments, so the brain evolved to co-ordinate that adaptation.

Another set of animals had appeared during the time of the dinosaurs: the mammals. These had evolved another special part of their brains, which was able to control and regulate their body temperature. As a result, mammals could be active at night and avoid the reptile predators that depended on the sun for warmth and energy. Mammals evolved in other ways, too: they began to suckle their infants and nurture them after they were born, which allowed the young animals a safe time to learn about the physical world around them and to explore. A small part of the mammals’ brain became specialized for adaptation and learning, so they were able to deal with unpredictable or changing environments. All this meant that when the world changed and the dinosaurs died out, the mammals were able to survive and take advantage of the ecological resources the dinosaurs were no longer using.

The mammalian brain, like that of other animals, adapted itself to the demands of its environment. Prey animals became highly sensitive to sensory information, developing acute reflexes enabling them to react quickly. Hunting animals developed in similar ways, as their survival required them to match the prey animals in order to catch them. Some animals were vegetarian, living only on plants; others were omnivores, exploiting whatever food sources they could find. And, most important of all, some of these lived socially, and shared their resources.

Since living socially was important, the demands of social interaction and co-operation meant that mammals lived in an ever-changing environment, so those parts of the brain that allowed them to deal with change and to communicate and pass on information became well developed. Animals living in social groups therefore developed multipurpose brains, which could adapt to different environments, interact with different individuals, spot new opportunities, and deal with problems. And in one particular group of mammals it became so important that it eventually overshadowed all the other parts.

When we look at a human brain today, almost all we can see are the two halves of the cerebrum: the part of the brain which we use for thinking, learning, communicating, deciding, imagining, and just about everything else which makes us human. The other, older parts of the brain are still there, but the cerebrum is so large that it has expanded to spread all over the rest. And since it’s the outer skin, or cortex, of the cerebrum which does most of the work, the cerebrum has become folded and wrinkled, so we can fit more surface area into the space. The human brain is one of the most remarkable things we know about, and understanding fully how it works is likely to keep our scientists busy for many generations to come.

The basic brain

In this book we’ll be exploring what modern neuroscientists have been able to find out about the ways that the brain functions. But even before we do that, we can learn a lot just from looking at the different parts of the brain and seeing how each part has evolved. Let’s begin by thinking about the most basic nerve functions a developing animal would need: to be able to move and to avoid pain.

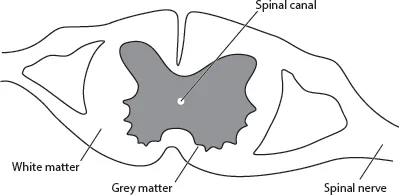

This takes us back to the ancient neural tube. We still have the equivalent of it in our human central nervous system, although it’s become a bit more sophisticated since then, of course. It’s the spinal cord – the tube of nerve fibres running the length of the spine, linking our body’s nerve fibres with the brain. If we look at a cross-section of the spinal cord, we can see that it really is a tube: it has a hollow in the middle that is filled with a nutrient fluid. That hollow is surrounded by what we call grey matter, which is mostly made up of nerve cell bodies, and the grey matter is surrounded by white matter, which is nerve fibres carrying information to and from the brain. So the spinal cord is the main route for information going between the body and the brain. That’s why people who experience damage to their spinal cord can become paralysed. Their brains may be trying to get their muscles to move, but they simply cannot get the instructions through.

Figure 1.2 The spinal cord in cross-section

Not all movement is directed by the brain, though. The spinal cord also controls some of our reflexes – the rapid muscle movements that happen in response to painful stimuli. This is what happens, for example, if you pull your hand away from a hot surface. You do it quickly, without thinking, because the message of heat and pain only needs to go as far as the spinal cord. When it gets there the message is instantly routed to the nerve cells, which tell your arm to move your hand away. It doesn’t need to go all the way up to the brain. That’s known as a reflex and, because it’s such a basic survival mechanism, it’s controlled by the oldest part o...