![]()

Part I

PHOTOGRAPHY, GENDER, AND MODERNITY

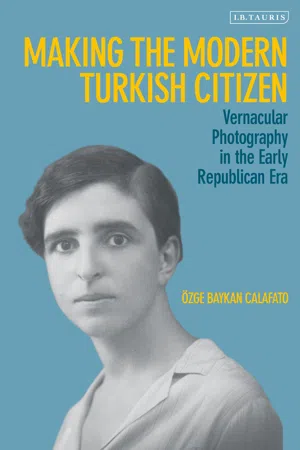

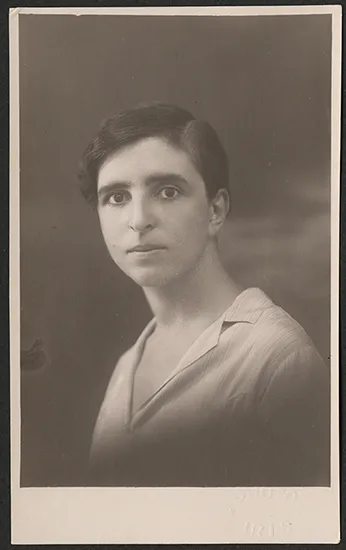

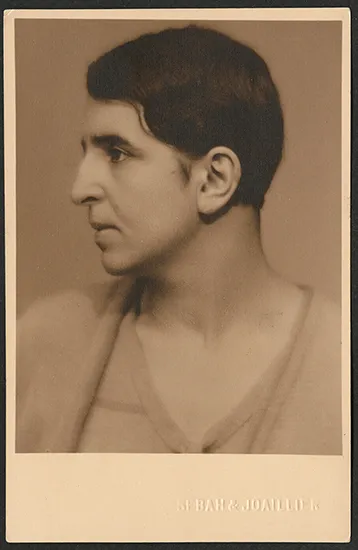

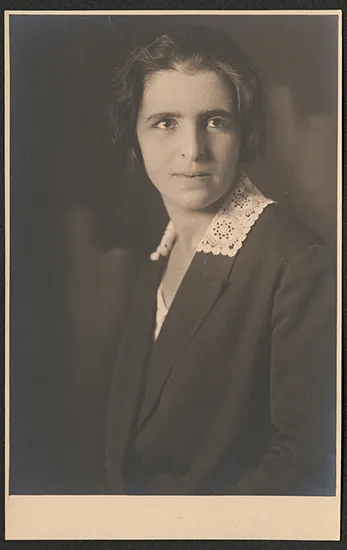

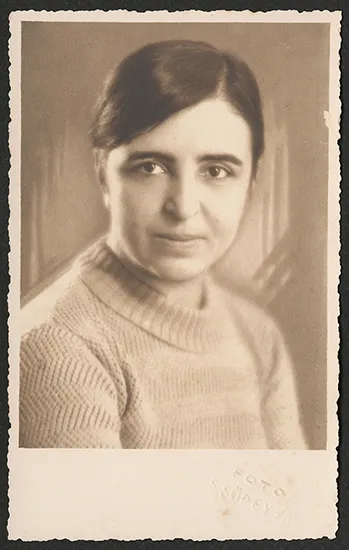

In 2014, I purchased a series of six images (Figures 1.1–1.6) from a second-hand bookshop that sells old photographs in the Taksim Cihangir area of Istanbul. Taken in five different studios, the portraits feature a young person with fine features posing in various outfits: a light linen shirt in Figure 1.1, a V-neck sweater in Figure 1.2, a patterned jacket in Figure 1.3, fur in Figure 1.4, a laced collar blazer in Figure 1.5, and a striped sweater in Figure 1.6. The hairstyles also differ in each portrait. In a few instances, the photographs have been retouched to give the hair relief or texture. In Figure 1.3, for example, the model has a wavy hairdo, reflecting a fashionable hairstyle for women in the 1920s and 1930s. In the same image, the mouth and chin appear to have been retouched. Despite these differences and alterations, however, the six portraits appear to be of the same person: in Figures 1.2 and 1.3, the pointy nose bears the same features, yet the beauty spots on both cheeks could be considered the decisive feature.

Figure 1.1 A studio portrait, Photo Iris, Istanbul, circa 1920s. 13.4 × 8.7 cm.

Courtesy of Akkasah, the photography archive at al Mawrid, NYUAD. Copyright al Mawrid

Figure 1.2 A studio portrait, Sébah and Joaillier, Istanbul, circa 1920s. 13.8 × 8.5 cm.

Courtesy of Akkasah, the photography archive at al Mawrid, NYUAD. Copyright al Mawrid

Figure 1.3 A studio portrait, Jules Kanzler, Istanbul, circa 1920s. 13.9 × 9 cm.

Courtesy of Akkasah, the photography archive at al Mawrid, NYUAD. Copyright al Mawrid

Figure 1.4 A studio portrait, Jules Kanzler, Istanbul, circa 1920s. 13.7 × 8.7 cm.

Courtesy of Akkasah, the photography archive at al Mawrid, NYUAD. Copyright al Mawrid

Figure 1.5 A studio portrait, Photo Français, Istanbul, circa 1920s. 13.3 × 8.5 cm.

Courtesy of Akkasah, the photography archive at al Mawrid, NYUAD. Copyright al Mawrid

Figure 1.6 A studio portrait, Foto S. Süreyya, Istanbul, circa 1920s–1930s. 13.7 × 8.6 cm.

Courtesy of Akkasah, the photography archive at al Mawrid, NYUAD. Copyright al Mawrid

The dates of the images are unknown. One can therefore only deduce a broad timeline based on the studio names, the type of photographic paper used, and the overall visual style of each studio portrait. Figure 1.6 seems to be the last of the series and was possibly taken a few years later than the rest, which I can trace back to the late 1920s or early 1930s. In this period, all five studios in the series were still active.

Four of the five Istanbul studios in which these portraits were made, namely Photo Iris (Figure 1.1), Studio Jules Kanzler (Figures 1.3 and 1.4), Photo Français (Figure 1.5), and Sébah & Joaillier (Figure 1.2), were run by non-Muslim photographers.1 The fifth studio is Foto S. Süreyya (Figure 1.6), which was established by the Muslim photographer Süleyman Süreyya Bükey in 1928.2 These studios may have been chosen because of their prominence or their familiarity, or simply because of a personal affinity, for instance, with the craft of Jules Kanzler, who enhanced the feminine aspects of the face with retouches.3

In Raw Histories, Elizabeth Edwards (2001a: 20) argues that “[p]hotography is like ritual or theater because it is between reality, a physical world, and imagination, dealing not only with a world of facts, but the world of possibilities.” With regard to making sense of photographs and what they show, she (2001a: 6) notes: “There is seldom a ‘correct interpretation’: one can say what a photograph is not, but not absolutely what it is.” As I was cataloguing these six images, I struggled to provide a description of the person portrayed. My interpretation is that in Figures 1.1 and 1.2, but particularly in Figure 1.2, the pose and clothing give the appearance of masculinity, while Figures 1.3–1.6 bring forward a sense of femininity.

How should I refer to the person portrayed in these photographs? Is this a man who enjoys dressing up as a woman? Is this a self-defined tomboy with indistinct features? Is the model an actor who relishes taking on an array of gender roles? Or do the photographs capture a fleeting moment of cross-dressing? The absence of dates makes it difficult to place the portraits along a chronological timeline, which keeps us from making assumptions regarding the potential evolution of this person’s appearance over time. Why does the attempt to say something about the gender identity of this person even matter?

As Joanne Hollows writes (2000: 27), “[g]endered identities and cultural forms are produced, and negotiated in specific historical contexts within specific and shifting forms of power relations.” In this process, the state has played an important role as “a powerful cultural agency helping to shape gender practices and expectations” (Hamilton 1998: 79). The way in which these six portraits indicate differently gendered selves is relevant in terms of what it has to say about how the Turkish modernization project, which was directly concerned with redefining gendered identities, particularly for women, was negotiated in photography.4

In this first part of my study, composed of two chapters, I will analyze how the evolving gender roles assigned to men and women are performed in photographic portraits from the first two decades of the Turkish Republic. As Holmes and Marra (2010: 1) write, since the 1980s, “language and gender research has shifted from essentialist approaches, which treat male and female as discrete social categories to social constructionist and performative approaches (Butler 1990), which emphasize the diverse, flexible, and context-responsive ways in which people do gender (among other identities) in different situations, and even from moment to moment within a situation.” Gender, then, is increasingly conceptualized as a dynamic performance through which it is continually produced, reproduced, and changed (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet 2003: 4 in Holmes and Marra 2010: 1). To study gendered performances in vernacular photography of the 1920s and 1930s, I draw on Butler’s theory of gender performativity as well as on scholarship that explores what it means to discursively do femininity and masculinity in a range of different social settings.5

Chapters 1 and 2 investigate the gender roles that, respectively, urban middle-class women and men adopted and represented through “performances of desire,” which Ryzova (2015a: 161) defines as “the production of particular selves that respond to socially situated expectations (masculine or feminine selves, modern selves, confessional selves, pious selves, respectable selves, playful selves, debauched selves); of social identities and communities (class, gender, family, confessional groups, networks of affiliation and association, networks of commerce); or forms of cultural memory.” Specifically, I will ask to what degree such performances accorded with the modernizing reforms of the Turkish Republic.

As Butler (2007 [1990]: 31) argues, “[t]he institution of a compulsory and naturalized heterosexuality requires and regulates gender as a binary relation in which the masculine term is differentiated from a feminine term, and this differentiation is accomplished through the practices of heterosexual desire.” The six images discussed above provide a vital vantage point from which to elaborate on the broader, sometimes contradictory relationship between photography and gender roles in the early Republican era, since these images urge us to probe the visibility of gender and rethink the normative forms of masculinity and femininity that the Turkish modernization project worked so hard to establish, impose, and propagate.

![]()

1

THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE NEW TURKISH WOMAN

As Göle (1996: 14) has persuasively argued in The Forbidden Modern, “the grammar of Turkish modernization can best be grasped by the implied equation established between national progress and women’s emancipation. More than the construction of citizenship and human rights, the construction of women as public citizens and women’s rights were the backbone of Kemalist reforms.” Unlike most national revolutions, the Kemalist revolution was primarily concerned with the reconstruction of the “ideal woman” instead of the “ideal man” (Göle 1996).

The reconstruction of an “ideal woman” started with the promotion of a Western, non-veiled appearance, associated with being civilized and progressive. The Kemalists perceived women as the “bearers of Westernization and carriers of secularism” (Göle 1996: 14). The Turkish nation-state relied heavily on a gender-based hierarchy and a hegemonic masculinity (Connell 1987, 1999) in assigning gender roles to the modern Turkish citizen. It did so while negotiating feminist movements in Western industrialized countries and a conservative Muslim pushback that wanted to exclude women from the public sphere. In addition, like many other modern political regimes of the time, the Turkish republic was built on the endorsement of heterosexuality, with love, sexuality, and desire tightly regulated through marriage and inheritance laws (Sancar 2017).

Recognizing the central role of visual representations of women in constructing the modern citizen for the Kemalist elites, this chapter will study how women performed their desired selves in photographs in the formative years of the Republic and how these self-representations corresponded to the regime’s efforts to construct the modern Turkish woman (also referred to as the Republican Woman). Specifically, I will look at the ways in which representations of Turkish middle-class women were formed, reproduced, and circulated in the 1920s and 1930s through vernacular photography. I will probe how self-representations of modern secular Turkish women differed in the public and private spheres, and how such representations might have contributed to the making of modern public life in the new Republic. First, I will focus on how women performed their modern selves in the semiprivate setting of the studio before and after the foundation of the Republic to demonstrate the continuities and disruptions with regard to the modernization of urban women. Second, I will discuss representations of modern femininities in group portraits taken in a public setting in order to question how the gender performativities evident in them compared to those in studio portraits. Third, I will look at photographs of beauty queens to show how women negotiated the secularization reforms, state feminism, and a conservative society that disapproved of the public display of female bodies. Finally, I will discuss the portraits of a Republican teacher to demonstrate the complexities involved in the contextualization of gender normativities in the 1920s and 1930s.

A growing number of publications have examined the negotiations of gender roles in politics, in the media, and in literature, as well as in daily life under the early Kemalist regime with a focus on women.6 There are also a number of works recounting the transformations in large cities (Duben and Behar 2014) and the countryside (Yılmaz 2013) in the early years of the Republic.7 I will draw upon these sources to contextualize the visual representations that I analyze in this chapter.

From Subjects to Citizens: Creating the Modern Turkish Woman

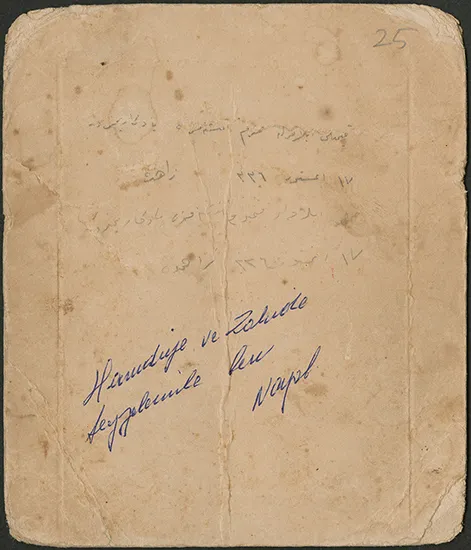

In Figure 1.7 from August 17, 1920 (August 17, 1336, according to the Rumi calendar), two women wearing the black çarşaf pose with a little girl for a studio portrait.8 The woman on the left wears pearl earrings; a sizable, matching pearl ring; a gemstone necklace and a fancy handbag with an elegant, beaded chain strap. The Turkish note in blue pen on the reverse of Figure 1.7 reads: “me, with Aunt Hamdiye and Aunt Zahide,” which suggests that the writer is the little girl in the middle, the daughter of a third sister not shown. The two women in black çarşaf must be the two aunts mentioned in the note. The note in pencil in Ottoman Turkish, however, was written by Zahide, who signs as “Zahiş,” a diminutive of Zahide. She writes in Figure 1.8: “A souvenir for our precious sisters and respectable brother-in-law.”9

Figures 1.7 and 1.8 (recto and verso) A family portrait, August 17, 1920. 16.4 × 13.9 cm.

Courtesy of Akkasah, the photography archive at al Mawrid, NYUAD. Copyright al Mawrid

Zahide and Hamdiye wear their çarşaf in a similar fashion: It reveals their neck and chest, serving as a coat. Under their çarşaf, they show off their beautiful jewelry, complemented by fashionable accessories including handbags and gloves. Their hair is only partially covered, and the face veil has already been removed, showing that the sisters are wearing makeup. Unlike the little girl in the ...