![]()

1 A Kellyan approach

At the age of 14, alone among my classmates, I took up the option to study Latin. Over two years, for three periods a week, I had individual lessons with an elderly woman teacher. In the eccentric independent school I attended, this teacher was one of the few members of staff who had stayed for more than a couple of terms. Her main subject was Scripture, as it was then called. By the time I made my choice to study Latin with her, I knew this teacher very well. To the whole group of my contemporaries, she was a figure of fun, laughed at for her old-fashioned clothes and pedantic manner, cruelly compared with the vital and glamorous young women teachers who passed briefly through the school. Scripture, her subject, was held in very low esteem. The lessons were occasions in which we vied with each other in diverting this teacher from the material she had prepared. Since she treated every inquiry with earnest seriousness, and apparently never recognized flippant or mocking intentions, it was, in fact, very easy to alter the direction of her lessons.

My reasons for choosing to study Latin with this teacher had to do with her description of what the subject would entail. Inviting us to take up Latin, she spoke of Aeneas’s mysterious journey, of the love poems of Catullus, of the dangerous political world which Cicero wrote about. It sounded like another version of English, which for me had been by far the most engrossing part of my school curriculum. And Latin, as taught by this teacher, did prove very much as I had anticipated. The texts we worked through were every bit as interesting, as moving, as human, as she had described them. My own progress in the subject also went well. Apparently impossible grammar seemed eventually, under this teacher’s tuition, to become understandable. I found myself acquiring a large vocabulary, and even, sometimes, a sense of the rhythms of the language.

Yet, for all their interest and enjoyment, these Latin lessons involved complicated feelings. I found my own position ambiguous. Among my friends, I had for a long time played my part in maintaining and elaborating an unkind mockery of this particular teacher. Now, in my Latin lessons, I experienced unmistakable affection from her. I was caught up in her own wide learning and real love for the subject she was teaching. I found gradually that I could not enter into the public currency of jokes against her; Scripture lessons became increasingly painful occasions for me. My private learning, which made me ‘special’, was both treasured and embarrassing. It involved an experience of the teacher which could not be shared with friends who knew her very differently. The relationship set me apart, cut me off from my social group in this area of our school lives.

What was this learning about? To say that I learned Latin does not seem adequately to encompass it. I did develop an understanding of certain classical Latin texts. But this understanding was framed by the outlook of one particular teacher, coloured by her feelings, her unique sense of the meaning, the vitality of the writings. In coming to appreciate Virgil’s poetry, I came to approach it from a particular angle, to take the direction towards it which my teacher somehow conveyed. By doing so, I necessarily changed my position towards the teacher herself, and this act subtly but irrevocably altered my position towards my friends. My learning – for all its interest and enjoyment, its opening of new horizons – was personally costly. It entailed complicated and painful feelings to do with loyalty and betrayal, solidarity and loneliness.

How, most basically, do we see education? A certain story, containing the essence of many age-old myths and fairy tales, is widely if implicitly shared. After an arduous search, a mysterious and sometimes dangerous journey, the brave and tenacious adventurer at last achieves his reward. He gains the keys of the kingdom. The world, with all its treasures – of knowledge, understanding, the whole cultural heritage – lies open to his taking. This is a story which sets the hardships, the confusion, the struggle of the learning endeavour against the richness of its prize. In its happy-ever-after ending, the learner who has stayed the whole long course, passed through each successive educational trial, triumphantly attains the ultimate goal – access to a world of understanding. It is in these terms that most of us usually see things. But what if we took another metaphor? Suppose we looked at the process of education as one version of the story of Adam and Eve.

For George Kelly, whose ideas have inspired this book, the biblical parable of Adam and Eve is the fundamental story of our humanity. In an essay entitled ‘Sin and psychotherapy’ (1979b),* he explores something of its meaning. The essay is a reflection on the situation of a middle-aged client who has sought all of his life to return to the Eden he knew in early childhood. But, like Adam, like all of us, he cannot go back. By eating the forbidden fruit, Adam and Eve have come to a knowledge of good and evil. And this is fateful knowledge. Through seeing moral possibilities where none existed before, we lose our simple delight in the way things are. The world cannot be accepted without question ever again; our knowledge of what might be makes us restless, keeps us searching. We can no longer take everything for granted. We now possess, for better or worse, ‘the awful responsibility for distinguishing good from evil’. There is no going back to the innocence we shared with animals and birds, to the paradise of our pre-moral world.

In the story we usually tell of education, the quest ends when learners take their hard-earned reward, and, following arduous endeavours, come at last into their own. But if our story is of paradise lost, this is only the beginning. Knowledge has consequences. The story of Adam and Eve does not end with their eating of the apple – nor even with the expulsion from paradise which followed this. Knowing what they now know, Adam and Eve cannot but live out the moral possibilities they grasp:

With knowledge come responsibilities, and with responsibilities come trouble. Adam and Eve, in this remarkably insightful story, sought the knowledge of good and evil, and that is precisely what they got, for they lived to see one of their sons grow to be a good man, and the other his murderer (Kelly 1979b, quoted in Maher, pp. 166–7).

In such a view, knowledge is not the end of the story, but rather the beginning of a new, qualitatively different chapter. It is a chapter entailing the transformation of the character of the protagonist. The questing knight of the traditional tale does not himself change when at last his mission is accomplished. But Adam and Eve are irrevocably altered by the knowledge they acquire. Adam begins to experience a new disturbing self-consciousness. Once happily unaware of himself as a separate being, he now finds he is alone and embarrassingly exposed; he sees with shame that he must cover his nakedness. In coming to know the world differently, we ourselves are transformed.

We think of knowledge, insight, understanding, as worthwhile in altogether simple ways. For learners struggling with their task, the treasures to be gained are of pure gold. Skies are cloudless in the kingdom of understanding. Yet, like Adam, we may find that we must buy our knowledge dearly. What we know may make us lonely in our social worlds; it may impose responsibilities we would far rather not have. It is not only martyrs, who, like Galileo, may have to suffer for what they come to know. The small girl whose elder brother insists on proving to her that Father Christmas is an illusion, must give up a specially delightful part of her early childhood. Christmas is forever changed; the magic cannot be recaptured. To those British people for whom the Second World War was the noble struggle of a brave little island under its heroic leader, later revelations of the bombing of Dresden, the betrayal of the Cossacks, were wholly repugnant, representing knowledge to be acquired only with the greatest reluctance.

In Kelly’s model, our personal construct systems define the understanding we each live by. This means that learning is never the acquisition of a single, isolated bit of knowledge. Our ways of seeing things are inextricably intertwined. To alter one assumption means that others, too, are brought into question. Understanding has implications; a change in one idea entails possibilities of having to rethink others. And this is just as true of school knowledge as of informal understanding. If art is really just a matter of colour, where does this leave all those careful pencil drawings you do at home, to the pleasure and admiration of your parents? Does this exciting new approach to maths render invalid all your earlier understanding of computational problems? Or, now that you begin to see how human affairs have always been affected by race, gender, social class, must the whole of history be rethought?

Some of the implications of learning involve risks that extend into the future. If, as a girl, you pursue your present fascination with molecular theory, where will it take you? Doing a physics option will put you among boys, and lead you in directions very different from those your friends are taking. If you follow up these interesting English studies, with consequences for the way you speak, you may find that you have become alienated from your own background. Going on with your guitar lessons might entail the possibility of discovering, in the end, that you cannot make it to the top.

As Adam found, to live by understanding rather than obedience means entering the difficult realm of existential choice. We have to give up the security of ignorance – the known boundaries to thinking and experience, the safety of shared ideas, the comfort of taking things for granted. Nor is it only individual ‘learners’ whose security is threatened by new ways of knowing. Societies are grounded in shared assumptions about human reality. To call any of those basic assumptions into question is to risk moving beyond the pale – into martyrdom, or madness. For most of us, such possibilities are very remote. But even much more limited extensions of understanding inevitably entail a questioning of conventional ideas, a refusal to be bound by traditional, established assumptions. As such, they pose their own challenge to the status quo.

In Kelly’s philosophy, we construct and reconstruct what we know about ourselves and our world. Yet this does not, I think, presuppose that each of us must recreate the wheel. Knowledge does not exist only in our heads; it is also out there, enshrined in laws, in cultural artefacts, in established practices. Though understanding arises only out of the interrogations that human beings put to their world, once acquired, it takes on a kind of independent existence, an authority. Cumulatively, it provides the whole frame of reference within which we, as individuals, construct the meaning of our experience. No one can step outside his or her culture, or develop terms that simply bypass its frame of reference. Yet cultural understandings differ across space and time. What we know, we know as members of a culture which has its own distinctive interpretations of reality. But these interpretations can never be final, only provisional. They remain open, potentially, to change. In every epoch, through the struggle of individuals and groups, new themes, new issues become salient, with consequent changes in social practice.

As Kelly insists, construct systems are personal. But this does not make them solipsistic. Though each of us inhabits a unique experiential world, psychological meanings must, if they are to be viable, be built together with others. The human enterprise depends on a shared social reality. The sense we make of our lives must also make some sense to others. And since human realities are, first and foremost, social realities, personal meanings have their essential currency in relations between people, rather than within some private, individual world. From the very beginning of life, interpretations – the meanings to be accorded to things – are offered and exchanged between infants and their caregivers. As babies grow into childhood, the conversational confirmations, challenges, comparisons, interrogations of personal meaning develop at a geometrical rate. A widening social experience brings awareness of competing realities, alternative constructions. Somehow these must be met and negotiated. A personal system of meaning has to be forged which is viable, liveable, yet which remains open rather than closed.

Education, in this psychology, is the systematic interface between personal construct systems. This view of formal learning puts as much emphasis on teachers’ personal meanings as on those of learners. Here, a Kellyan approach stands apart from most educational psychology, which, while generally focusing on the distinctive ways in which individual pupils see things, tends to lump teachers together. The knowledge they represent, the meanings they offer are, it is implied, essentially standard. Underlying this definition of teachers, in terms of a standardized curriculum, are certain absolutist assumptions about knowledge itself. If we believe that history, science or maths embody particular ultimate truths about the world, then we can see all teachers of these subjects as representing essentially the same sort of expertise. But we cannot take this view if knowledge is provisional. Learning, from this perspective, is not a matter of acquiring what Kelly dubs ‘nuggets of truth’, a treasure-house of human certainties. In learning, we cannot ever achieve final answers; rather we find new questions, we discover other possibilities which we might try out. Knowledge is ultimately governed by constructive alternativism; everything can always be reconstrued. Reality is not to be pinned down forever in a standardized school curriculum. The understanding that teachers offer is essentially provisional – for the time being. And, for all that school knowledge has high social consensus and is grounded in the whole cultural heritage, it is necessarily personal. It has its significance within the personal construct system of the particular teacher. Since each person inhabits a distinctive world of meaning, the curriculum of education is constructed afresh, and individually, by every teacher who offers it.

Our personal construct systems carry what, in the broadest possible sense, each of us knows. It is these systems which allow us to ‘read’ our lives psychologically. They locate us, moment to moment, within events. They define the stances we take. They represent our possibilities of action, the choices we can make. They embody the dimensions of meaning which give form to our experience, the kind of interpretation which we cast upon events. Since none of us can know anything of the world, except through the meanings we have available to us, the dimensions we have constructed – our constructs – are crucially important. Of course these dimensions of meaning are not isolated and separate. Our experience of the world is complex, all-of-a-piece, rather than a succession of different and unrelated categorizations. Constructs are essentially interwoven within a personal system of meaning.

It is this interrelationship that produces the richness of implication, the complexity, the depth of any human perception. Seeing her new class, the experienced teacher instantly gets the feeling of a tricky group. The perception carries with it a whole network of other interpretations – of past experience, future expectations, possible strategies, potential outcomes. These constructions define the teacher’s position towards the class group, her assumptions about them, the kinds of engagement possible for her. They are likely to be available to her not as explicit, verbal labels, but rather as an implicit set of guidelines towards the situation, felt and sensed rather than put inwardly into words. Our construct systems encompass much more of what we know than we could ever say; and the more fundamental the knowledge, the less easily accessible it probably is to explicit verbalization.

All this gives an overriding importance to the network of personal meaning which those who teach and learn bring to educational contexts. Nor is this just a matter of academic definition. As a man who combined with his university appointments a life-long involvement in psychotherapy, Kelly himself needed to develop practical strategies for eliciting personal meaning. The latent, intuitive, experiential issues involved in personal distress and breakdown have to be acknowledged, made explicit, before they can be explored and reflected upon. And it was to elicit this very personal, intimate material, that Kellyan techniques were developed.1 Such techniques are, above all else, conversational. This means not only that they are essentially informal, but that they are rooted in a credulous rather than a judging attitude to what is offered. They are committed to listening, if possible, to what is not, as well as what is said, to hearing something of the connotations surrounding particular constructions.

For most people familiar with personal construct psychology, it is the repertory grid technique2 which defines this approach par excellence. This is essentially a categorization, or sorting task, in which a number of items are judged in terms of dimensions that can be applied to them. From statistical associations among the judgements made, conceptual linkages are inferred. I have found that a much simpler approach is often equally fruitful, and avoids many of the problems associated with repertory grids. Truer to genuine conversation, it does not force the person into making judgements which feel artificial, which do violence to natural ways of thinking. Nor does it remove the material offered, to be submitted privately for statistical analysis. The interpretation of what the material may mean remains open, as much the property of the subject as are the initial constructions. For want of a better title, I call this technique the Salmon Line.

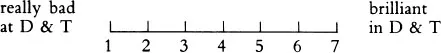

When children are introduced to new areas of the school curriculum, they make their own sense of what is presented to them. A few years ago, I was involved in studying a second-year design and technology class (Salmon and Claire 1984).3 In order to compare the perceptions of the children with those of their teacher, I asked both to talk about this school subject in relation to a line:

First, I invited all the pupils to make a mark on the line which they felt represented where they stood at the moment in general competence in the subject. Had they always been at this point, or somewhere lower? Again, I asked for a mark to show where. What point on the line did they expect to reach eventually? Having obtained these judgements, I then asked the children to flesh them out for me. What could they do now in D & T that they had not been able to do when they stood lower? How had they come to be able to do these things, not having been able to do them before? What would they be able to do in future that they could not do now, and again, how would this happen? Then I invited the children to place on the line someone they knew who was very competent, and someone who was very incompetent, in D & T. Again, I ...