II.Distribution of Competence as a Criterion for a Typology

A.The Rules on the Distribution of Competence between the Union and the Member States

The legal justification or explanation for mixity boils down to the principle of conferral, defined in Article 5(2) TEU. Under that principle, the Union shall act only within the limits of the competence conferred upon it by the Member States in the Treaties to attain the objectives set out therein. Competences not conferred upon the Union in the Treaties remain with the Member States. When the conclusion of an international agreement or convention falls in part within the competence of the Union and in part within that of the Member States, there is, in principle, either an obligation or a possibility to conclude that agreement or convention as a mixed agreement.

The more precise nature of a mixed agreement depends however on the way in which the competence to conclude international agreements is divided between the Union and the Member States in respect of a given agreement. That in turn depends on the general provisions of the Treaties governing the scope and nature of the Union’s competence9 as well as the power-conferring provisions (legal bases) authorising, either expressly or by implication, the Union to conclude international agreements in the various areas of its competence. While the concrete attribution of competence between the Union and the Member States under a given mixed agreement depends on the characteristics of that particular agreement, the provisions of the Treaties governing the division of competence between the Union and the Member States also enable us to classify mixed agreements for the purpose of establishing a typology of mixed agreements.10 The purpose of the present section is to present such a typology based on the criterion concerning the distribution of competence.

Before presentation of the typology, there will be a brief look at the rules of the TFEU governing the scope and nature of the Union’s external competence. The scope of that competence in respect of a given subject matter or area is determined by the relevant legal bases,11 read in conjunction with Article 216(1) TFEU,12 while the nature of that competence is determined by Title I of Part One TFEU governing the categories or areas of Union competence. Insofar as the nature of the Union’s competence is concerned, there is a fundamental distinction between exclusive and non-exclusive Union competence.13 Where the Union has an exclusive competence,14 only it may legislate and adopt legally binding acts, the Member States being able to do so themselves only if so empowered by the Union or for the implementation of Union acts (Art 2(1) TFEU). In areas of non-exclusive Union competence, however, the existence of that competence does not a priori preclude the Member States from exercising their competence. The notion of non-exclusive competence – which is not included in the Treaties – comprises the following categories of competence, in each of which the implications of the exercise of the Union’s competence are different. In areas of shared competence,15 Member States may exercise their competence to the extent that the Union has not exercised its competence (Art 2(2) TFEU).16 In the areas where the Union has competence to carry out actions to support, coordinate or supplement the actions of the Member States,17 the exercise of Union competence does not supersede the competence of the Member States (Art 2(5), first subpara, TFEU). The same is probably also true for the Union’s competence to coordinate the economic and employment policies of the Member States (Art 2(3) TFEU),18 and to define and implement a common foreign and security policy (Art 2(4) TFEU), even though the Treaty is silent on the implications of the exercise of the Union’s competence in those areas. While the exercise of Union competence in the areas of shared competence may turn that competence into an exclusive one through the operation of the AETR principle19 now codified in Article 3(2) TFEU20 or, in any event, preclude the exercise of a corresponding Member State competence under Article 2(2) TFEU, the breadth of the above categories of non-exclusive competence, extending to the great majority of the policy areas of the Union (Arts 4 to 6 TFEU), shows that, in the attribution of competence upon the Union, non-exclusive competence is the rule and exclusive Union competence very much an exception. This aspect concerning the distribution of competence between the Union and its Member States provides the principal explanation for the wide-spread practice of concluding mixed agreements. Finally, insofar as no Union competence exists, there is, by definition, an exclusive competence of the Member States, in either a ‘horizontal’ or a ‘vertical’ sense. This distinction will be explained in detail further on.

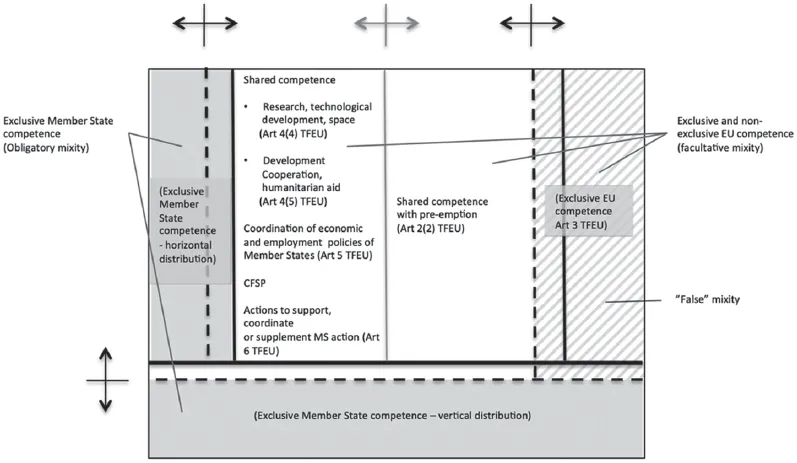

Drawing on the above rules and principles governing the distribution of competence, one could present the general structure of a mixed agreement depicted in Figure 1.1, which could then be used as a ‘matrix’ for drawing up of a general typology (or typologies) of mixed agreements based on the criterion of distribution of competence:21

Figure 1.1 Structure of a mixed agreement

Such a typology (or typologies) would however easily risk becoming all too abstract and, as such, potentially incapable of describing the actual practice of mixity. Therefore, to us, a preferable option would be to use the above ‘matrix’ as a mere conceptual tool for understanding and assessing certain categories of mixed agreements that have originated from, and evolved in, the actual practice of the institutions, including the case law of the Court of Justice, and that now have a firm footing in the doctrine. In that regard, the most important distinction concerns the distinction between, on one hand, ‘mandatory’ mixed agreements (section II.B) and ‘facultative’ mixed agreements (section II.C). Reference is sometimes also made to so-called ‘false’ mixed agreements, that is, mixed agreements that could not legally have been concluded through the mixed procedure (section II.D). For the reasons of space, the present typology is limited to these principal categories and their variants.