INTRODUCTION

The modern history of aphasia undoubtedly begins with Paul Broca (1824-1880) (Benson, 1985; Geschwind, 1964b). Although the anatomist and phrenologist Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828) localised, as early as 1819, the “organs” for speech articulation and word memory in the orbital region of the frontal lobes, it was Broca who first revolutionised the medical community when he discovered that lesions in the posterior part of the third left frontal convolution induced expressive speech deficits, which he called aphemia (Benton, 1991). Thirteen years after Broca’s discovery, Carl Wernicke (1848-1905), a young German neuropsychiatrist, generated a second major revolution in the understanding of the cerebral localisation of aphasia when he published a monograph entitled Der aphasische Symptomcomplex. Eine psychologische Studie auf anatomomischer Basis (1874/1977). In his monograph, Wernicke described the salient features of sensory aphasia (now termed Wernicke’s aphasia) that include grossly impaired auditory comprehension and fluent but paraphasic spontaneous speech.

Wernicke’s contribution was by no means restricted to defining the clinicopathological characteristics of the sensory aphasia syndrome. He also developed a general schematic model to interpret anatomofunctional aspects of both normal language acquisition and aphasie disorders (Fig. 1.1) as well as a new classification of these disorders. Wernicke’s hypothetical diagram of language function and his new classification of aphasias were rapidly accepted by other leading aphasiologists of the period preceding World War I, such as Bastian, Charcot, Lichtheim, Dejerine, and many others (Benson, 1985).

WERNICKE–LICHTHEIM CONNECTIONIST MODEL

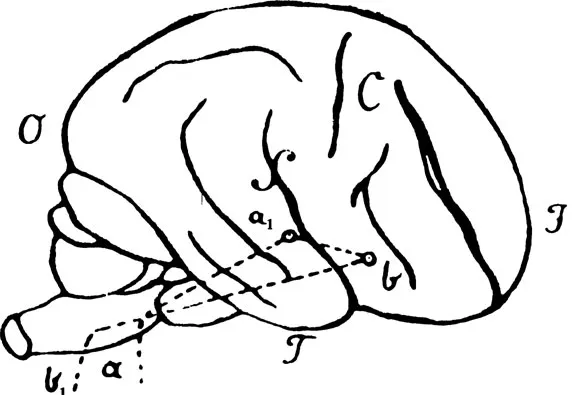

Wernicke (1874/1977) believed that language disturbances occurring after brain damage were the consequence of impairment in psycholinguistic functions (understanding spoken language, reading, writing, and so forth) that were represented in centres with specific anatomical locations. On creating his diagram of language representation in the brain, Wernicke was extremely conservative and made the effort to restrict the number of centres and their linguistic functions (Caplan, 1987, p. 54). He suggested that expressive language, including word and sentence repetition, was mediated by a “reflex arc” represented in the cortex surrounding the Sylvian fissure. He envisaged that incoming sounds were conveyed via the acoustic nerve (a) to the centre for acoustic images located in the cortex of the posterior temporal lobe (a1). This sensory centre was connected by major subcortical fibre tracts to the centre for motor images located in the inferior frontal region (b) and its efferent pathways concerned with speech (b1). Wernicke then suggested that these two speech centres and the commissure a–b were the first structures used in the normal acquisition of language through imitation of what the child hears. He went on to speculate that in subsequent stages of language development other fibre systems, independent of “sound images”, were regularly used for spontaneous speech, a theory that was later accepted by Lichtheim (1885).

Wernicke (1874/1977) noted that two patients (Cases 3 and 4) of the 10 sensory aphasies he originally described had good auditory comprehension. By that time, he had become particularly interested in the analysis of milder cases of sensory aphasia. He found that in such cases, the symptom-complex was characterised by hesitant and laborious spontaneous speech and word-finding pauses in the presence of intact comprehension of spoken language. This combination of language deficits was termed commissural aphasia (Leitungsaphasie or conduction aphasia). Despite the fact Wernicke had pointed out that the interruption of the neural path linking the a1 (centre for acoustic images) in the temporal lobe with b (centre for motor images) in the frontal lobe would induce conduction aphasia (Henderson, 1992), he failed to predict that repetition should be abnormal in this type of aphasia (Geschwind, 1964b). Lichtheim (1885) believed that the impairment of repetition may be one of the most relevant characteristics of the syndrome. He further argued that a lesion involving the fibre tracts interconnecting the motor and sensory speech centres at the level of either the Insula Reili or the superior longitudinal (arcuate) fasciculus, but sparing the major cortical speech centres would induce a combination of fluent paraphasic spontaneous speech, good auditory comprehension, and impaired repetition. In the same article, Lichtheim (1885) described a clinicopathological case study (patient JSB) who confirmed his prediction. For several years, Wernicke was reluctant to accept the characteristic triad of language deficits in conduction aphasia, until 1904, when his assistant, Karl Kleist, showed him a typical clinical case of conduction aphasia (Geschwind, 1963).

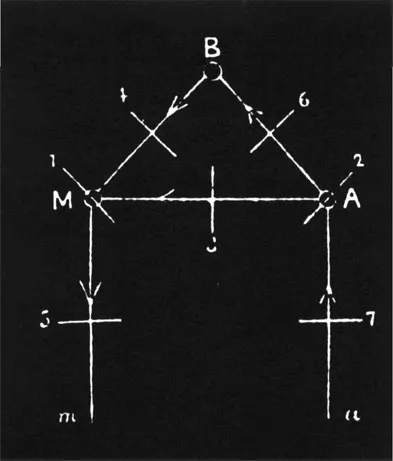

Lichtheim (1885) was profoundly influenced by the pioneer work of both Broca (1861 and 1863) and Wernicke (1874/1977) in his development of the localisationist concept of aphasia. He was particularly interested in the description of other types of aphasia which in his view could not be explained entirely on the basis of Wernicke’s model, and which he believed resulted from the interruption of the pathways connecting major speech centres rather than from damage of the speech centres themselves (Caplan, 1987; Lichtheim, 1885). Based on previous models of language functioning and on the analysis of aphasie patients, Lichtheim complemented the schema of language representation in the brain drawn by Wernicke by including new centres and commissures. Following the same line of thought as Wernicke, Lichtheim developed his schema by starting with the acquisition of language by imitation (repetition). He first postulated the existence of specific centres for auditory images A and motor images M that were interconnected by a commissure completing a “reflex arc”. The innovation of Lichtheim’s schema was the incorporation of a new centre that he termed B, and which he viewed as the “part of the brain where concepts are elaborated” (Fig. 1.2).

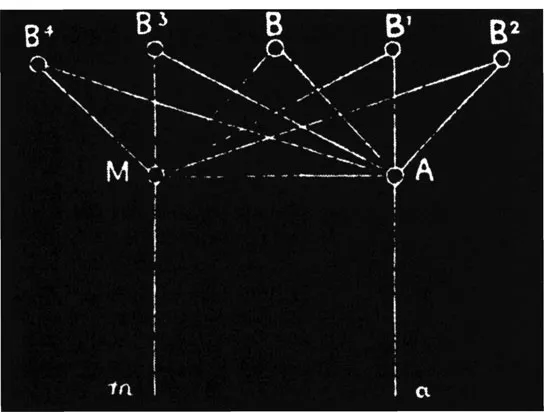

Based on the clinicoanatomical observations of Broca and Wernicke, Lichtheim assumed that the centre M was located in the inferior frontal convolution, centre A in the temporal convolution, and that the commissure linking A-M passed through the insula. While Lichtheim accepted that the “reflex arc” created by Wernicke was sufficient for simple language repetition and monitoring correct speech, he was convinced that other brain areas had to be used when less automatic aspects such as volition and intelligence are incorporated into language function. In other words, Lichtheim pointed out that when intelligence is required in the service of language, this function is accomplished through pathways linking the auditory centre A with various peripheral nonlanguage areas in which the concepts are elaborated (p. 436). Lichtheim also hypothesised the existence of pathways connecting the concept centre B with M, which he believed were necessary for volitional or intelligent speech. Although he was convinced that volitional speech relied on the commissure B-M, he additionally suggested that the phonological information used in verbal output is controlled by both the direct connections linking centre A with M and the indirect connection A-B-M (Arbib, Caplan, & Marshall, 1982; Lichtheim, 1885).1 According to Lichtheim’s model, the “concept centre” B (Begriffe) cannot be localised in a specific anatomical site, “but rather to result from the combined action of the whole sensory sphere” (p. 477). In addition, he indicated that the commissural pathways linking the concept centre B with the motor M and sensory A speech centres (commissures M–B and A–B) were not only two distinct and separate commissures, but a radiate set of converging fibre tracts coming from various unidentified regions of the cerebral cortex to the A and M centres. From a clinicoanatomical point of view, Lichtheim suggested that damage to these widely distributed commissures across the left hemisphere (BM, B1M, B2M, and so forth) would induce speechlessness and/or word-deafness (Fig. 1.3). He also suggested that simultaneous lesions in these commissures at their entrance to either centre A or B may induce the same language defects as if they had been damaged at more distant sites. He further hypothesised that since the motor centre M can be activated by two separate pathways, the disruption of either would induce different patterns of repetition (see further discussion in Butterworth & Warrington, 1995; McCarthy & Warrington, 1984).

LICHTHEIM AND THE INNER-COMMISSURAL APHASIAS

Inner-commissural aphasia

In 1885 Lichtheim, based on his own cases, first reported a variety of motor aphasia which he believed was the result of an interruption of pathways linking the concept centre B with the motor speech centre M. The resulting language impairment was characterised by loss of volitional speech and writing with preserved understanding of spoken and written language as well as copying, reading aloud, and repetition. This condition was termed inner-commissural aphasia. He interpreted language deficits as well as preserved language functions as follows: Spontaneous speech would be diminished because ideas stored in the concept centre B could not access the motor speech centre A necessary for verbal expression. By contrast, he interpreted that speech understanding would be preserved because both the centres A and B and their connections were spared. Finally, Lichtheim speculated that basic speech functions such as repetition and oral reading would also be spared because the centres A and B and their subcortical connecting pathways were intact. Wernicke accepted the clinical description of this novel kind of aphasia, but replaced the term inner-commissural aphasia by the now widely accepted transcortical motor aphasia. Lichtheim exemplified this type of aphasia by reporting a case of traumatic aphasia in an article entitled On Aphasia (1885) which was published in the prestigious neurological journal Brain. What follows is a summary of the most relevant clinical details of such case (pp. 447-449).

The patient, known as Dr CK, was an adult bilingual (German-French) man who had worked as a medical practitioner until he suffered a traumatic brain injury in a carriage accident. Following the accident Dr CK remained unconcious for three hours; on awakening it was noted that his speech was severely affected and he could say no more than “yes” and “no”. He also had impaired swallowing and voluntary buccofacial movements, and a moderate hemiparesis with normal sensation was noted in his right limbs. Language examination in the ensuing days revealed that “whilst his vocabulary was still meagre, it was observed that he could repeat everything perfectly”. CK could not write spontaneously, but his writing to dictation and copy were preserved. He was examined by Lichtheim six weeks after the accident. Neurological examination disclosed only a mild weakness in his right facial nerve and leg, and impaired recognition of objects palpated with his right hand. The profile of language impairment had also improved to the point that Lichtheim described CK’s spontaneous speech as “copious”, although he then stated that “he does not talk much, and speaks in a drawing manner”. During running speech, Lichtheim noted that the patient omitted words and produced paraphasias both in German and French. CK was aware of the paraphasic distortions he produced during object naming and attempted to correct himself. In this regard, Lichtheim commented “the auditory representation of words he cannot find were missing; he cannot name the number of syllables of them”. Although CK could comprehend and repeat these unnamed words, he could not retain such words in his memory. Repetition was normal for short but not long sentences. Auditory and written comprehension were both normal. CK’s narrative writing, like his spontaneous speech, was fluent but replete with meaningless words. Copy and dictation were normal. Lichtheim reported that one month later CK’s language defects had improved considerably, and only isolated deficits could be found in writing and naming.

Even though Lichtheim was unable to confirm the localisation of the responsible lesion in this case, he speculated that inner-commissural aphasia would result from white matter lesions located at the base of the third frontal convolution (p. 478). He arrived at such a conclusion after reviewing clinicopathological details of some previous cases (p. 478): “Thus in the case of Farge, we find that the patient had a right hemiplegia after a severe apopletic seizure. He could say only a very few words; but could repeat correctly what was said, at least the first words of a sentence … The autopsy revealed integrity of Broca’s area; but in the white matter beneath was found a patch of softening, the size of a small egg.”

The subsequent publication of a case of transcortical motor aphasia (innercommissural aphasia) associated with a small lesion of the white matter beneath the motor speech region by Rothman (1906) provided further support for Lichtheim’s original formulation on the neurological basis of transcortical motor aphasia.

Inner-commissural word-deafness

Lichtheim (1885) also went on to predict that a lesion interrupting the commissures between the centre of auditory images A and the concept centre B would provoke a sensory aphasia with fluent paraphasic speech, echolalia, and impaired understanding of spoken and written language. While some symptoms were coincidental with those described by Wernicke under the rubric of sensory aphasia, Lichtheim suggested that since the lesion would not interrupt Wernicke’s arc, the faculty of repeating words, reading aloud, and writing to dictation should be preserved. He further commented, “Owing to the interruption of communication between A and B, there must be a complete loss of intelligence for what is repeated, read aloud, written to dictation by the patient” (p. 453).

In his 1885 article, Lichtheim reported on a second aphasie patient who could repeat language, but who had fluent oral expression and poor understanding of spoken language. The patient, JU Schwarz, was considered to have innercommissural word-deafness (transcortical sensory aphasia):

Spoken Language—The disturbance in his power to understand it i...