![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Globe around Magellan

The World, 1492 to 1521

And the channels of the sea appeared, the foundations of the world were discovered, at the rebuking of the Lord, at the blast of the breath of his nostrils.

—2 Samuel 22:16

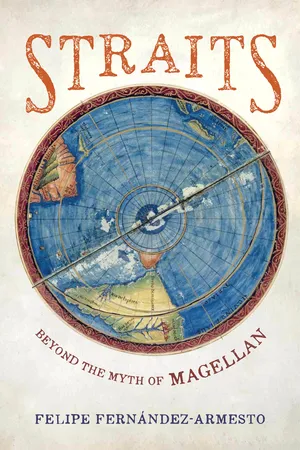

FIGURE 1. The Indian Ocean, where Magellan’s overseas adventures began in 1505, was the world’s richest arena of commerce at the time. Until the 1490s most fifteenth-century European maps of the world showed the Indian Ocean as enclosed and inaccessible from Europe by sea, thanks to the influence of the Geography of the revered second-century Alexandrian cosmographer Claudius Ptolemy. Interpretations of his text informed most educated Europeans in the late fifteenth century, as in this example, reproduced, from a model of the 1480s, in Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia, which appeared in successive editions in the 1550s, showing the ocean surrounded by enveloping lands. Putti blow winds onto the world from a cloudy firmament. Magellan retained elements of Ptolemy’s image, including the peninsula, here marked “India extra Gangem,” to the east of India, and the island of Taprobana, corresponding roughly to modern Sri Lanka. Spanish cosmographers claimed that the meridian of the great bay marked “Sinus Gangeticus” marked the dividing line between zones of navigation agreed upon by Spain and Portugal. Courtesy of the James Ford Bell Library, University of Minnesota.

“Write what you know,” said Robert Graves, who rarely observed the maxim. It has become a shibboleth for writing teachers but seems contemptible: facile, challengeless, narrow-minded, anxious for success. The unknown is magnetic: an invitation to endlessly unwinding problems, a lure to the receding horizon that seduced Magellan, or a way into the improbable stories he composed for himself in his head and tried to act out in his life. In sticky, smelly classrooms, amid Gradgrind-mark schemes and marginal ticks, history is “about facts.” But, for me, facts are there only to feed problems: insoluble problems—for preference—that flirt and flit as you grasp at them.

I think I know as much about Magellan as you can know in your head. I can unpick the contradictions of the evidence. I can reproach predecessors with errors and straighten tangles in the chronology. I can get patternless details into focus: I know, for instance, as previous inquirers have known, how many arrows (21,600) and compass needles (thirty-five) appear in Magellan’s ships’ manifests, how many hourglasses (eighteen), how many barrels of anchovies and tons of biscuit (below, p. 110).1

I also think I know—or sense convincingly—a lot about his heart: the tragically flawed social ambition, the heroic self-delusion, the vexing self-righteousness, the cruelly streaked sense of humor. They all appear in the pages that follow. I can trace the way his journey through life changed him, and reconstruct the strange mood of religious exaltation in which he died. But there’s gut knowledge too, which eludes me. Magellan was one of at least 150 men who died on the voyage he led. If you leave out those who survived by deserting or in captivity, the death rate was about 90 percent. Even by the standards of the day, when failure was routine on alarmingly overoptimistic journeys, Magellan’s project beggared belief. Objectively considered, the chances of survival, let alone success, were always minimal. As we shall see, the cost in lives bought no quantifiable return. Despite previous historians’ assertions, the balance sheet of crude profit and loss ended in the red. The voyage Magellan captained failed in every declared objective.

What made such an egregious adventure attractive, not just to the men who risked it, but also the backers who put money into it? I am not sure I know or can know that. Life was cheap, for reasons, partly intelligible, to which we shall come in a moment. “To set sail,” said Luis de Camões, the well-traveled poet who turned Portuguese maritime history into verse in 1572, “is essential. To survive? That’s supererogatory.”2 What made such a shocking inversion of common sense seem reasonable? Why were seamen’s lives so dispensable—so much cheaper than everyone else’s? What made Magellan and some of his men persist as their prospects worsened? What induced the king of Spain and hard-headed merchants in Seville and Burgos to believe in Magellan? Why would they put up money for a proposal from a man who came to them with a reputation for treachery, a dearth of relevant experience, and a scientific sidekick, Rui Faleiro, who, to the psychiatry of the day, was literally, certifiably insane?

• • •

To approach the problems we have to start by trying to understand the constraints and opportunities of the world around Magellan.

That world was riven with paradox. Every textbook will tell you that the centuries in which Magellan lived were an “age of expansion,” when stunning new departures happened. In Europe the retrieval of classical tradition intensified in the Renaissance, which equipped minds for new art and thought and endeavor and which spread to much of the rest of the world, including parts of the Americas and sub-Saharan Africa: the first genuinely global intellectual event.3 The so-called Scientific Revolution was exhibiting early signs when Magellan took to sea, enabling the formerly backward West to catch up with and (in some respects, over the next hundred years or so) to overtake Chinese science and technology. Meanwhile, a global ecological exchange swapped life-forms across a formerly divergent world, spreading creatures, plants, and pathogens, for good and ill, across the globe. A persistent historical tradition even claims that Magellan’s lifetime roughly coincided with “the origins of modernity”: the distribution and divisions of world religions were taking on something like their present configurations; some of the world’s most widely and creatively deployed languages and literatures were taking shape in forms intelligible to today’s readers. The world’s major civilizations—Christendom, Islam, and the Buddhist world—literally expanded, engrossing territory and people, stretching out to each other across chasms of culture, spreading contacts, conflicts, commerce, and contagion.

How did all that happen in what was also, worldwide, an age of plague and cold?4

On the face of it, we should not expect large-scale migrations, long-range conquests, or spells of invention in a period of severe environmental dislocation or harsh conditions.5 Climate and disease set the context for everything else that happens; and climate is supreme, because diseases depend on it. Magellan’s lifetime came roughly in the middle of one of the most severe interruptions in global warming since the end of the Younger Dryas, nearly twelve thousand years ago. The “Little Ice Age,” from the mid-fourteenth to the early eighteenth century, inflicted conspicuous and measurable harm on the societies it affected, spreading starvation, worsening wars, provoking rebellions, incubating plagues. The coldest spell was toward the end, generating stories of freak freezings, from the king of France’s beard to entire salt seas.6

During Magellan’s career no conditions or events remotely so extreme occurred, and in the first half of the sixteenth century temperatures seem to have been milder than immediately before or after. Nevertheless, in parts of the world from which quantifiable data are available, spring and winter temperatures were typically between one and two degrees lower, on average, than what we now consider normal (represented by the average in the first half of the twentieth century).7 As we shall see, Magellan’s men complained of the cold they experienced and threatened to mutiny because of it.

Lethal, recurrent bouts of disease accompanied the cold.8 At the time, people called them plagues: maladies associated with a complex ecology, involving rodent hosts and fleas as vectors.9 The afflictions in question were persistent and impressive. From the mid-fourteenth century to the early eighteenth—the period exactly matching the cold era—no living subject was portrayed more often in Europe than the Grim Reaper, reveling in his deadly duties, selecting dancing partners without regard to age, sex, or appearance.10 In 1493, a little before Magellan became a page boy in the Portuguese court, the Nuremberg Chronicle included a remarkable text under an image of dancing dead, in various stages of putrescence—gleefully displaying rotting flesh, jangling their bones, with worms wriggling and entrails dangling.

They are irrepressibly jolly. It is tempting to say that the dead exhibit joie de vivre. The words of the song to which the cadavers rise from their graves appear in the text. “There is nothing better than Death.” He is just, because all deserve him. He is equitable, because he treats poor and rich alike. He is benign, because he frees the old from sorrow. Visiting prisoners and the sick, he is kind in obedience to commands of Christ. Mercifully, he liberates victims from suffering. He is wise, despising worldly pleasure and deploring the vanity of power and wealth. When the Age of Plague receded, Death became less familiar and therefore, perhaps, more feared. Nowadays, people treat him with evasion. They speak of him in euphemisms, in which “the loved one” is said to “pass away.” Magellan and his contemporaries had an uneasy familiarity with Death that it is hard for us to retrieve.

Local recurrences of plague defied, to some extent, expectations that visitations would leave survivors protected by immunity. The pace of microbial mutations, perhaps, explains the persistence. While the bubonic-plague bacillus, Yersinia pestis, was responsible for many, if not most or all, of the outbreaks, evidence that survives in victims’ DNA includes variations, small and significant, over time.11 One feature of the environment was constant: the reasons for the way then-prevalent strains of the bacillus responded to fluctuations in temperature have attracted a great deal of inconclusive research; the link with cold, however, is conspicuous. The Black Death of 1348–50 followed a fall in Northern Hemisphere temperatures. The retreat of “plague” coincided with the resumption of global warming.12

During Magellan’s adulthood, though population was edging upwards in Europe, plague hardly abated. England experienced three outbreaks of “great plague” or “great pestilence” in the first two decades of the sixteenth century. From the frequency with which the city council issued measures of quarantine and of what we should now call “lockdown,” Edinburgh seems never to have been free of plague from 1498 to 1514.13 In Leipzig in 1521 quacks hawked Germany’s “first brand-name medicines” as remedies for plague.14 In 1520 what can fairly be called an international medical conference met in Basel to propose universal measures of prevention.

In the Iberian peninsula, in the harshest winter of Magellan’s lifetime, in 1505–6, plague struck Évora, Lisbon, Porto, and Seville. Plagues appeared in Barcelona in 1501, 1507, 1510, and 1515. Those of 1507 and 1510 reached across Spain’s eastern seaboard and beyond, into western Andalusia. The years 1507–9 were by some measures the most deadly since the Black Death. The outbreak in 1507 killed a tenth of the prebendaries of Cadiz Cathedral, while the Andalusian priest and sedulous chronicler Andrés de Bernáldez claimed to witness thirty thousand deaths in a single month in May. The previous year, claims that Jews were responsible for spreading plagues helped to provoke a massacre in Lisbon.15 While Magellan’s expedition was at sea, plague broke out in Valladolid and spread to Valencia, Córdoba, and Seville, where his fleet was launched. An earthquake in Játiva in 1519, an exceptionally rainy year, was taken as presaging the plague that followed in Lisbon, Valencia, Zaragoza, and Barcelona, where it persisted until 1521.16 The plague and cold did not exclude other routine sources of suffering, such as drought in 1513 in the Gudiana valley and more generally in 1515 and 1516. Drought and famine menaced much of Portugal in 1521–22.17

In one respect, Magellan’s career coincided with an unprecedently aggressive development in the global disease environment: the transmission of Old World pathogens to other continents, along with the other biota of global ecological exchange, which Columbus inaugurated when he swapped products of the Old World and the New on his first two transatlantic voyages.18 The arrival of Spanish settlers in Hispaniola in 1493, or perhaps of successors in subsequent voyages, introduced unfamiliar diseases with which native immune systems could not cope. In a terrible acceleration of mortality in 1519, the friars to whom the Spanish monarchy had confided control of the colony abandoned hope of keeping the natives alive.19 Near extinction followed. By the time of Magellan’s voyage, Spanish intrusions had generalized the effect around the Caribbean and projected it onto the Central American mainland. Mortality rates of up to 90 percent became normal wherever “the breath of a Spaniard” broadcast disease.20 The cheapness of life was not the result of glut anywhere in the world of the time. Magellan’s era differed from ours not so much, perhaps, because of the low value people put on life as because of the high value they put on death. Death in those days was the real lord of the dance.

• • •

Meanwhile, despite the unpropitious circumstances, in widely separated parts of the world, economic activity and territorial conquests speeded up like springs uncoiling. An “age of expansion” really did begin, but the phenomenon was of an expanding world, not simply, as some historians say, of European expansion. The world did not wait passively for European outreach to transform it, as if touched by a magic wand. Other societies were already working magic of their own, turning states into empires and cultures into civilizations. Beyond the reach of the recurring plagues...