![]()

I no longer know what there is behind this wall, I no longer know there is a wall, I no longer know this wall is a wall, I no longer know what a wall is. I no longer know that in my apartment there are walls, and if there weren’t any walls, there would be no apartment.

GEORGES PEREC, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces

We shut the doors behind us to enclose ourselves within the walls of a room. A basic element of all homes and buildings, a wall’s solidness allows it to go unnoticed as a commonplace visual security blanket, one that we cover with pictures of loved ones. We gently pierce the skin of a wall with nails to hold up the frames that contain our memories. These frames with the faces of our children, our parents, our lovers, and our friends become the focal points of a wall, making it a mere background to how we present our rooms to any visitors we allow in. We don’t consciously question the validity of these walls—they are hard, strong, and functional. The world is outside; we are inside. That division helps produce a sense of security, permitting us to shut off the lights, burrow under blankets, and fall peacefully asleep.

When I visited the Aida refugee camp, located about a mile north of Beit Jala in the central West Bank, I spoke with a man who has witnessed the holes in homes produced by Israelis and their weaponry. Seeing abject destruction firsthand, he understood that soldiers could enter his room at any time during the night or simply destroy the walls to get in otherwise. This older man, sitting in a backless chair, had witnessed the violent reality of conflict, of his walls having lost their security. No longer solid separators between inside and out, this man’s walls were always in a state of potential erasure. The walls lost their hardness, their strength, and their functionality. This refugee’s privacy was instead permeated by the overall Israeli-Palestinian conflict, his private space melding into one amorphous dangerous public space.

This refugee’s personal walls became unknowable because of the material reality of “The Wall.” Described by the Israeli government as an “anti-terrorist fence,” this $3 billion wall has been built incrementally since 2002, slowly closing off spaces and people.1 The Separation Wall, made of eight-meter-high concrete slabs and fences weaving their way along fiercely contested borders between Israeli and Palestinian land, is a barrier that is the epitome of Foucault’s governmentality. Planned and built according to an evolving strategy, the Separation Wall has reshaped “the distribution of inter-visibilities, define[d] flows of circulation . . . determine[d] the possibilities and impossibilities of encounters.”2 For this old man in the Aida refugee camp, the Separation Wall made “what is behind the wall” unknowable. The wall, anchored firmly in the land and patrolled by soldiers who can deploy artillery within minutes, is a border keeping Israel unknown to Palestinians—if they even come near the wall, they are dealt with as potential terrorists.

Walls, however, are material and immaterial; the very physical wall sharply cutting through the two nations has ideological influence outside the site lines of its own presence: no matter where Palestinians are in relation to the wall, Israel sees them as potential terrorists. The wall’s immaterial presence in Palestinian lives has deep repercussions in daily life, much like Georges Perec’s epigraph to this chapter: “I no longer know what there is behind this wall.” The Separation Wall has made Israel unknowable for those who live within the Aida camp, but their homeland of “Palestine” has been made enigmatic as well. This man is always enclosed behind the Separation Wall, and in turn, the walls of his own home are rendered equally unknowable. In conflict areas, what has always been previously clear—for example, the walls of your home are walls—suddenly becomes opaque. But although this refugee’s walls have become something he can’t quite recognize, the Separation Wall is viciously knowable.

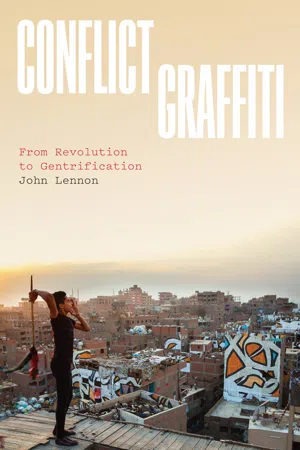

The Separation Wall is the focal point for Palestinian resistance to Israeli policy. The wall is a symbol of overall Israeli incursion into Palestinian land and also the actual barrier blocking Palestinians from their ancestral homes, which were confiscated during the Nakba in 1948, when more than seven hundred thousand Palestinians fled or were forced from their homes during the war with Israel. When people place paint on the wall with statements or images in opposition to Israeli governability, they are, in essence, trying to make the walls of their own homes knowable again (plate 1). By painting what some Palestinians have called the “Apartheid Wall” with slogans, pictures, or even advertisements, they are revealing the wall in a new light, reimagining its surface, and forcing it to be legible in a different script, from a new hand. The Separation Wall has physical and ideological influence on walls throughout Palestine and the world; many of those who write protest graffiti on the border wall are attempting to resist this brutal authority, to rebuild their own walls in their own homes. When Israel ordered the Separation Wall to be built, it simultaneously created a public space to resist it. At the edges of the disputed borderlands between Israel and Palestine, the wall is a space for resistive efforts against the occupation of Palestinian land. This chapter will focus on walls—both border walls and city walls—in order to understand how spray paint can be used in opposition to state repression.

A border wall is a physical and ideological barrier; graffiti is one material and symbolic tool used to combat state policy. The Separation Wall physically manifests a Zionist political desire, articulated by Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin when he campaigned for office in 1992 under the slogan that Israeli-Palestinian relations should be simply “Us here. Them there.”3 “Here” and “there” are, of course, arbitrary. Regardless of this Zionist wish, the border between Israel and Palestine is not completely closed.4 Undoubtedly imposing, the Separation Wall is a working border: seventy thousand Palestinians are allotted daily work permits to legally cross into Israel from the West Bank and another twenty thousand to thirty thousand sneak through drainage pipes and holes in the wall and fences to get to work and see family.5 Israel, somewhat reliant on Palestinian labor (and many Palestinians are dependent on wages from Israel), allows Palestinians—under heavy surveillance—to walk through the wall to arrive at their jobs. In this sense, the wall is malleable, stopping some people and allowing others to go through; what seems to be a solid mass, then, has surprising openings. “Walls work” rhetorically justifies the building of border walls, but the work those walls do is much more complicated than just stopping people from crossing a border.

The Separation Wall is one of many state-sponsored barriers imposed with great fanfare, heated opposition, and limited results. Even before Donald Trump’s bombastic demand for a “great” wall between the United States and Mexico (discussed later), the 2006 Secure Fence Act passed by Congress called for the completion of an 850-mile wall and fence separating Mexico from parts of California, Arizona, and Texas.6 This wall, the second most famous barrier wall in the world, was built with many of the same subcontracting firms and uses similar surveillance technologies. The two further seek to legitimize each other as state lawmakers from Israel and the United States point to the other for their justification.7

During Trump’s presidency both of these walls were often in the news, but they are only two of the many walls that zigzag along national borders. Saudi Arabia, for example, is building a 1,100-mile fence along the Yemen border that includes numerous ten-foot-high concrete walls.8 Uzbekistan built a wall on its disputed border with Kyrgyzstan; government officials claimed it was for security purposes, and critics argued that the wall building was a state-sponsored land grab.9 Botswana constructed a barrier between itself and Zimbabwe ostensibly to stop the spread of foot-and-mouth disease across nations but also, and more important, to stop the movements of migrants into the country from its poorer neighbor.10 In the autonomous North African cities of Ceuta and Melilla, Spain built high-tech border infrastructure, complete with infrared sensors and imposing walls, to curb migrants from leaving Africa and crossing the Strait of Gibraltar.11 China built walls to keep Korean refugees out of the country, and North Korea erected its own walls to keep out the Chinese. As millions of refugees from Syria, Iraq, and other states experience devastating humanitarian catastrophes, a steady stream of politicians, backed by the rise of ultraconservative parties in the United States, France, Germany, Poland, and other European countries, have demanded more walls to keep (an interchangeable) “them” out.

All governments claim that border walls, erected for a variety of political, economic, and social reasons, exist for one primary reason: protection. A nation’s sovereignty rests upon the bedrock idea that the government can protect the nation’s people. In the twenty-first century, this idea is eroding quickly, revealing fault lines created by the neoliberal policies that have spurred the migrations of people, capital, and cultures. Numerous suicide bombings throughout the Middle East; massive “theatrical” killings in cities such as Paris, London, and Madrid; and the 2001 destruction of New York’s World Trade Center—all have symbolically cast doubt about the ability of nations to protect their citizens. The increased number of border walls attest to ways states react to such vulnerabilities through material and symbolic performances of power. By building imposing walls, politicians can stand in front of them in choreographed photo ops, emphasizing the physical structure in order to allay the psychological fears of citizens.

This type of border structure, according to Trevor Boddy, is an architecture of “dis-assurance.”12 The walls are emblems, large symbolic illustrations that the state is “doing something” to protect its citizens. An analogue to the color-coded “threat level” in the United States, these walls (or sometimes steel slats) show the state as consistently on red alert. They are visual manifestations of the state’s rhetoric that it can protect its citizens from “aliens” intent on harming the country, whether terrorists, drug runners, or “thieves” of jobs and services.13 Fears of terrorists blowing themselves up and migrants finding employment are ideologically connected at their base: both reflect a fear of “barbarians” at the gate ready to infiltrate the “civilized” nation.

Wendy Brown brilliantly shows in Walled States, Waning Sovereignty that such walls are, in actuality, highly ineffective and costly structures that, at best, funnel bodies, capital, and violence into equally dangerous alternative routes (like the Israeli wall) and, at worst, are obviously ineffective (like the US-Mexican border fence). As Janet Napolitano, former Arizona governor and secretary of homeland security under Barack Obama, once stated, “You show me a 50-foot fence and I’ll show you a 51-foot ladder at the border.”14 Walls do not effectively keep migrants out of the United States: this becomes clear when considering the large number of Irish migrants working construction jobs in Woodside, Queens, or of Mexican migrants picking strawberries in central Florida. In reality, these migrants are an integral part of the nation’s disposable, low-cost labor force.15

If these walls are costly and ineffective, why do politicians and large swaths of the population favor them? As one rancher on the Arizona-Mexican border cynically but accurately stated, “The government isn’t controlling the border, it’s controlling what Americans think of the border.”16 Such large walls allow people to point to a physical object of deterrence, which reassures them of the state’s power. In the age of globalization, however, national sovereignty has been partially forfeited to a global market, and the flow of the multitude, to use Hardt and Negri’s term, is transnational.17 These walls are not meant to stop invading national armies, but rather individuals—potential terrorists, poor people, smugglers, asylum seekers, among others—whose numbers proliferate at certain historical moments and reduce at others. Although border walls may deter certain actors, they cannot stop the flow completely. In that way they have been likened to dams, since the flow of people can be, at times, somewhat regulated. As Hurricane Katrina proved, though, through its devastation of New Orleans in 2005, storm surges can catastrophically breach even the biggest walls. But despite the breaches revealing their ineffectiveness, at moments of perceived political crises, the cry for bigger walls is exponentially louder. The desire to see the government physically “doing something” spurs politicians to pour money into lucrative building contracts for bigger border walls.

Wall building is a centerpiece of Donald Trump’s political performance. During the 2016 US presidential campaign, when Trump labeled Mexican migrants as rapists and thieves, hyperbolically announcing that, if elected, he would force the Mexican government to pay for a “beautiful” wall across the whole southern border, he raised the specter of the 9/11 terrorist attack and manufactured consent of the populace by playing on an exaggerated fear of enemy combatants entering the United States. But his performance also evoked the specter of the North American Free Trade Agreement and the post-2008 recession, with its high unemployment and loss of (white) working-class manufacturing jobs. He was playing with xenophobic and masculine tropes of the wealthy white male forcing the poor brown Mexican subordinate to do his bidding.18 By linking racist rhetoric to an actual physical object, he declared himself a political “outsider” who knew who belonged inside the United States. A platform that involves walling terrorists “out” and keeping jobs “in” is fear-mongering fiction. Even still, Trump’s claims that Mexico would build his border wall proved beneficial by directly playing to his political base’s fear of losing their jobs by race-blaming “foreign” labor. Despite outrage elsewhere, his poll numbers rose sharply, and he was the darling to a certain subsection of the Republican Party, which positioned him to become the nominee in a crowded field of candidates.

As Walter Benjamin states in “On the Concept of History,” “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule.”19 Trump’s fear-mongering xenophobia is not novel but a significant part of US immigration history. Examples from the nineteenth century abound—from the West Coast border closing to contain the “yellow menace” to the numerous signs in stores throughout the East Coast that “Irish need not apply.” In the twentieth century, US policy evolved to intern people of selected races, such as the ...