![]()

1

THE UPPER PENINSULA

Most Michiganders know the joke about how we traded Toledo for the Upper Peninsula (and then you insert your own punchline about Ohio). No matter how one feels about our neighboring state to the south, we can agree that the Upper Peninsula (UP) is a land that features some of the most beautiful terrain in the state. The UP also boasts a beer history as unique as the pleasant peninsula itself.

Other regions in Michigan were heavily influenced by German brewers, but the UP can claim forebears from France. The French part of Canada, known as New France, encompassed the area we now call the UP. The first economy was based on furs, thanks to the great number of beavers in the area. Early French settlers also traded brandy, rum and some beer to the local Natives during these early times.

Both the colonial Americans and the French enjoyed spruce beer, a brew made of spruce that dates to the 1500s, when explorers were dying of vitamin C deficiency. The son of an Iroquois chief, Dom Agaya, advised boiling the tips of spruce, fir, cedar or other coniferous trees and then drinking the resulting tea as a treatment for this vitamin deficiency. From that spruce tea came biere d’epinette, or spruce beer. By the time the French settlers arrived in the UP, beer of this type was well known, as it was loaded with necessary vitamin C and was fairly easy to make. Though area Natives had the ingredients to make the brew—tips from spruce trees, syrup, yeast and water—the practice never became common among them.

The UP housed three military posts at a time when the U.S. Army saw beer as a “healthy and recreational drink,” as it believed that beer consumption did not lead to the alcoholism and violence associated with hard liquor. Copper Harbor had a noncommercial brewery set up in the 1840s to supply daily rations of beer to the soldiers at Fort Wilkins. Additionally, beer produced in Detroit was then shipped to the UP, even before the discovery of copper and iron and the subsequent opening of the mines.

By the mid-1800s, the economy of the UP changed from fur trading and military outposts to copper and iron mines. In 1841, the discovery of copper deposits was revealed, followed by the discovery of iron ore three years later. These announcements led to an influx of emigrants from all over Europe. The German brewers arrived, and soon, their beer replaced spruce ale.

COPPER COUNTY

Nickolas and Catherin Voelker arrived in the late 1840s, eventually settling in Sault Ste. Marie. They took in two boarders, Joseph Clemens and Nickolas Ritz, and the three men established a small brewery. On June 26, 1850, they advertised in the Lake Superior Journal that their “brewery… would furnish [the community] with all articles in their line as good and on as reasonable terms as can be purchased elsewhere.” This brewery, whose name is lost to the ages, operated about five or six years before the men moved to Copper County.

This region of the western UP included the communities of Eagle River, Ontonagon and Houghton. Prior to Prohibition, most UP breweries were located in Copper County. Like what happened elsewhere in the state, as immigrants began arriving in the UP, breweries began to open.

Franz Hahn came to America in 1853, landing in Eagle River. He traveled to Milwaukee, where he began brewing, and later returned to Houghton in 1859. There, he spent two years working with William Ott of the Union Brewery. Hahn and his brother began their own brewery, which saw success until a fire devastated the location in 1873. Undaunted, they rebuilt within two years, creating an extensive stone brewery with a capacity of ten thousand barrels annually. Unfortunately, the Panic of 1873, along with the fire losses, led to the suspension of their business in 1875.

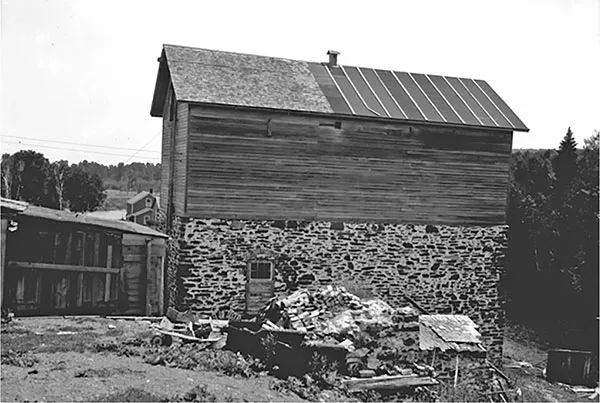

A side view of Knivel Brewery (undated). Courtesy of the Michigan Technological University Archives.

Franz’s story does not end there, however. He went on to manage the Houghton Bottle Beer Brewery, which was the first of its kind in the area, producing and bottling eight hundred barrels of beer annually. Henry Hofen’s Houghton Bottle Beer Brewery began brewing by the barrel in 1876 and began bottling in 1880.

Early brewers Nickolas Voelker and Joseph Clemens both jumped back into the business. The latter opened his brewery in 1855, while the former brewed in Ontonagon County, assisted by numerous Prussian brewers and a teenager from Ohio named Michael Gitzow. In Houghton, William Holt, an emigrant from Prussian, brewed alongside a half dozen of his fellow immigrants.

As copper mining took off in the early 1860s, demand for alcohol outweighed production, such that liquor from Detroit and other places was imported. Saloons popped up early, and liquor was always available in the hotel bars, stores and taverns that dotted the landscape. Breweries in the mid-1800s included the Eagle River Brewery, which was started by a Prussian immigrant named Frank Knivel and operated from 1855 to 1910. Rockland, a mining village of around one thousand people, boasted the Biggi and Kelley Brewery in the mid-1870s.

The Union Brewery enjoyed on-site spring water, which led to particularly excellent beer that was advertised with the motto: “the beer that pleases.” The Union Brewery brewed beer from 1857 to 1899, when it was sold to Bosch Brewing Company. Its main brands were Rheingold, Royal Brew, Rheingold porter and a malt tonic. These were distributed in Hancock, Calumet and South Range.

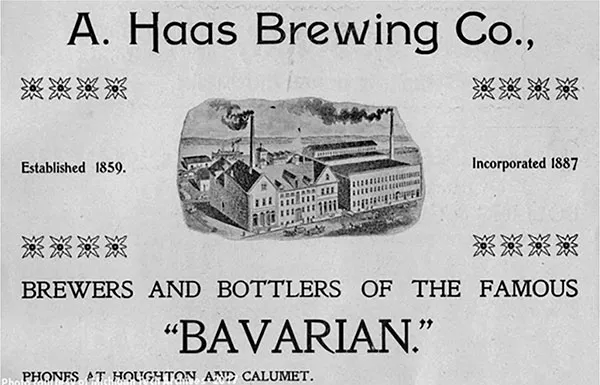

Haas

Adam Haas was born in Bavaria, Germany, in 1822. He began his career as a cabinetmaker in his native country and married Eva Lorsch. They had a son and daughter while still in Bavaria. Haas came to the United States at the age of thirty and moved directly to Houghton. First, he made his living operating boats between Portage Lake and Eagle River. He moved about ten miles away from his home but returned to Houghton in 1854 and began working as a trader of wine and liquor. In 1859, he constructed the first brewery in Houghton. The log building boasted a ten-barrel copper kettle and made porter and lager, enlarging as demand grew. In 1875, Haas acquired the stone brewery that formerly belonged to Franz Hahn, and along with this, his capacity for brewing enlarged to six thousand barrels per year. Haas served both as a commissioner of highways and the local coroner and had ten additional children with Eva.

Haas remained an active businessman until his death in 1878. The A. Haas Brewing Company soldiered on with help from Eva Haas and the couple’s daughters and sons. At a time when women were denied most opportunities, four Haas daughters served on the company’s board; their sons Joseph and Adolph served as president and vice-president, respectively. Using hand-blown glass bottles to distribute, the company brewed lager and Bohemian beer. By 1900, it was producing twenty-five thousand barrels annually. The family sold the brewery to a stock company in 1901, and operations ended in 1918 with state prohibition. On August 21, 1933, the beer began flowing again, as the Haas Brewing Company reopened at its original location in Houghton. Renovations and remodels made the facility one of the most contemporary breweries in the UP, and it is credited as the first in the UP to produce beer in cans.

The operation moved to Hancock in 1941, taking over the Park Brewery space, where it advertised that its “famous spring water” gave “the people the finest glass of beer they can drink, regardless of cost.” Some of the company’s standard beers were Extra Pale Beer, Haas Bock and the generic-sounding Haas Beer.

Haas. Courtesy of the Michigan Technological University Archives.

Haas advertisement. Courtesy of the Michigan Technological University Archives.

In 1952, the name changed to Copper Country Brewing Company. Unfortunately, with increased pressure from big breweries, such as those in Detroit, Milwaukee, St. Louis and points beyond, the newly named brewery could not compete and closed in 1954.

Bosch Brewing Company

Born in Baden, Germany, in 1850, Joseph Bosch came to the United States with his parents in 1854. His father brewed in Port Washington, Wisconsin, where Joseph learned the business. A young Bosch made his trade in the industry, working at Schlitz in Milwaukee, as well as other breweries in Cleveland and Louisville. After landing in Copper County, Bosch opened Torch Lake Brewery in 1874, brewing almost two thousand barrels in his first year. The company sold mostly to saloons and boardinghouses, and it also relied on the miners working in Red Jacket (now Calumet) as its loyal customers.

The company’s love of and commitment to the local area was present from the start, and it continued through the decades. Early on, Bosch sold farmers his malt and supplied them with a fresh, cold beer while they waited for their orders. More locals were brought into the business in 1876, when Bosch formed a partnership with three men and changed the company’s name to Joseph Bosch & Company.

Using its artesian well water, which the company claimed benefited liver, kidney and stomach problems, the brewery flourished, brewing four thousand barrels a year by 1883. In these early days, selling bottled beer was rare in the UP, but Bosch realized the promise in this venture and started a small-scale bottling operation in 1880. By 1883, beer from about one thousand of its annual barrels was sold in glass bottles.

Tragedy struck on May 20, 1887, when a fire wiped out much of Lake Linden, taking the brewery with it. Demand for the company’s beer led to a quick recovery, so it reopened in September that same year. In just over a decade, it was the largest brewery in the entire Upper Peninsula, making about sixty thousand barrels a year. In 1899, it enlarged its operations with the purchase of the old Union Brewery near Houghton.

Bosch boasted branches and storehouses in multiple locations, including Houghton, Eagle Harbor and Ishpeming. Around the same time, Joseph served as the president of Lake Linden’s First National Bank (which he helped organize), operated two saloons (legal in the days before Prohibition) and tended to a family that consisted of his second wife, Kate, and five children. He later served as the mayor of Lake Linden.

Bosch billboards welcome you! Courtesy of the Michigan Technological University Archives.

All the while, Joseph Bosch nurtured local connections, with advertisements touting his beer being as “refreshing as the sportsman’s paradise” and using the “soft spring water” from the local spring. Pictures in the advertisements showed fishermen and skiers, tying the brand to the natural beauty and outdoor sportsmanship of the area. Other advertisements can now be seen as almost comical—like the 1903 advertisement for the company’s malt tonic that says it is good “for convalescents…the weak and overworked, for nursing mothers.…Physicians recommend it.”

Like almost every other brewery, Bosch struggled through Prohibition. The company placed many local advertisements pleading for temperance rather than prohibition, but eventually, it had no choice but to cease brewing alcoholic beverages. At least one advertisement shows one way the company made money: selling a brew called Bock-Edge, with an alcohol content of less than ½ percent.

After the end of Prohibition, the company began brewing beer again, focusing on its Houghton operations rather than its operations in Lake Linden. It remodeled the Scheuermann Brewery to become one of the most efficient breweries in the state.

Joseph Bosch passed away in 1937, leaving behind a legacy of service, commitment to local business and a love of brewing. After Bosch’s death, Katherine Bosch (identified as his daughter in some records and granddaughter in others) and his grandsons James and Phillip Ruppe assumed control of the company. Their leadership led to increased sales and growth. This was due, at least in some part, to the incredible brand loyalty from the community and other local leaders. It became the third-largest employer in the area, peaking at 100,000 barrels of beer in 1955.

In 1965, high Michigan beer taxes, a decrease in sales and mounting competition from national brands led to talks of closing the brewery. Fortunately, all was not lost, as the community came together, gathering local executives, workers and employees, so that the family could sell to local investors. One of the key figures of this effort was Charles Finger of the International Union of United Brewery, Flour, Cereal Local 251, who served as the company’s vice-president and brewmaster. Along with chief advertiser James Jeffords, Finger toured the area, rebuilding the brand’s image as it spoke of the spring water and brewing techniques used by the company. The brewery promoted itself on TV and in papers, which led to an increase in sales in the late 1960s. In particular, it marketed the Light Sauna Beer, which resembled the Finnish kalja, an after-sauna beverage that is popular in Finland.

The last keg of Bosch going to Schmidt’s Corner Bar. Courtesy of the Michigan Technological University Archives.

Despite the marketing and public appearances, sales continued to decline, and the company sold its trademarks to the Jacob Leinenkugel Brewing Company. That large brewery hired Bosch’s master brewer, Vincent Charney, who continued to brew the signature brand in its traditional flavor. Even though devoted fans continued to buy and drink the product, profits eventually fell off, and Leinenkugel stopped producing Bosch in 1986.

In a ceremony on September 28, 1973, the last keg of “true” Bosch beer (brewed before the sale of the trademarks to Leinenkugel) was loaded onto a wago...