![]()

1

CREATING A NEW RANGE ROVER

When the third-generation Range Rover, or L322, model was announced in 2001, all the publicity focus was on its exciting new features. Ford, who had bought the Land Rover business in summer 2000, was understandably keen not to dwell on the fact that it had had almost no involvement in the model’s creation and it was only in later years that the real story gradually became apparent. In fact, what Ford called L322 had started life back in 1996 as a project called L30 when BMW had owned the Land Rover marque, and Ford had taken it over from the German company as a turnkey project.

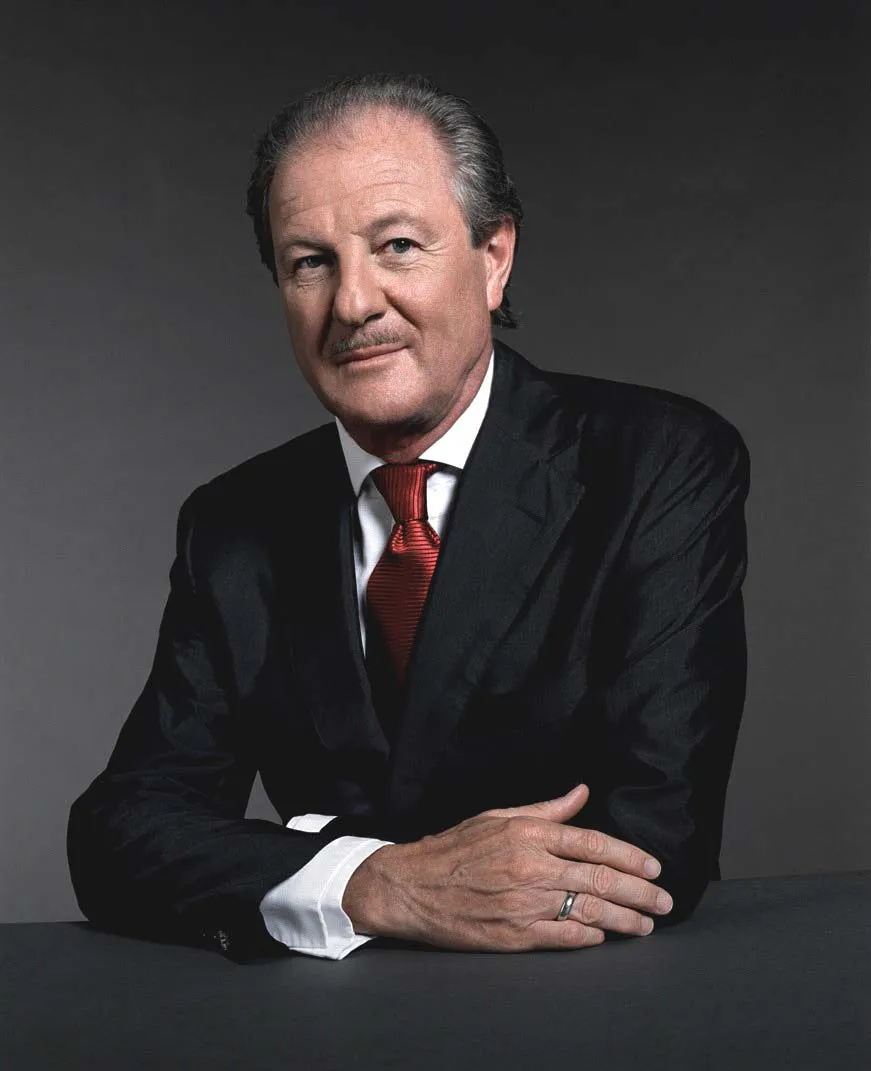

Dr Wolfgang Reitzle was head of R&D at BMW and oversaw the initial integration of the Rover Group with the German company. He was the driving force behind the new Range Rover.

Within those five years between 1996 and 2001 lies a fascinating history that is still not widely understood today. In fact, the story of the third-generation Range Rover can be traced back even further – to January 1994 and BMW’s purchase of the Rover Group from British Aerospace. At that stage, the German company appointed its highly respected R&D chief, Dr Wolfgang Reitzle, to oversee the early stages of the integration between the two car makers.

Reitzle was keen to get to grips as quickly as possible with the company’s products, especially those that were in the pipeline for the future. He was a great admirer of the original Range Rover and owned one himself, which he used regularly to take him from his home in Munich to the ski resort of Kitzbühel in the Austrian Tyrol. He considered it the only vehicle available that fulfilled all his needs and it was this passion for the Range Rover that had been behind his initiation of BMW’s E53 project – the vehicle that would be launched in 1999 as the X5.

Reitzle was a great enthusiast of the first-generation Range Rover, but he was much less enthusiastic about its planned replacement, which had been signed off for production and was to be introduced in autumn 1994. According to End of the Road: BMW and Rover – A Brand Too Far by Chris Brady and Andrew Lorenz, ‘on his first visit to Land Rover after the BMW acquisition, Reitzle […] climbed into the new vehicle, donned an aircraft eye mask and spent five minutes touching every inch of the cabin. He then got out and wrote a list of seventy features that he believed should be changed.’

David Sneath was appointed Chief Engineer for the 1999-model Range Rover, but when that was cancelled he was moved to the new L30 project.

The new Range Rover was then so close to production that it was too late to make major changes, but of course Land Rover had already begun to make tentative plans for its midlife update, which was scheduled for autumn 1998 and the 1999 model year. David Sneath had been appointed as Chief Engineer to oversee the update programme, but he had barely settled into the job when there was a major change of plan. Clearly anxious to improve a model he saw as unsatisfactory, Reitzle decided that the 1999 model-year variants needed a more radical overhaul. So Sneath and team found themselves putting together a revised 1999 model-year package that better matched Reitzle’s vision.

Central to the revised plan were new engines. The long-serving Land Rover petrol V8 was close to the limit of its development potential and would be replaced by a far more modern BMW design. BMW’s diesel engines were already acknowledged to be the best of their kind – in fact, Land Rover had already agreed to buy in its 2.5-litre turbocharged diesel for the new Range Rover – and the German company could supply a further improved version. So the revised plan for the 1999 model-year facelift incorporated a 3.0-litre update of the existing 2.5-litre diesel, plus 3.5-litre and 4.4-litre versions of BMW’s latest M62 petrol V8.

There was a fourth engine, too, and this was part of Reitzle’s plan to extend the Range Rover into a higher price bracket. In the mid-1990s, the most expensive models cost just over £60,000, but Reitzle now envisaged a £100,000 Range Rover. Inevitably, this would have very high levels of luxury and convenience equipment, but central to it would be BMW’s flagship engine – the 5.4-litre M73 V12 that was already in production for the company’s 7 Series saloons and, from 1998, would also go into the new Rolls-Royce Silver Seraph. With 322bhp and 490Nm of torque, it was vastly more powerful than any existing Range Rover engine, the most powerful of which delivered 225bhp and 376Nm.

For most of 1995 and well into 1996, work on the 1999-model Range Rover focused on this strategy. Although the 3.5-litre V8 was dropped early on, 4.4-litre V8s were built into several ‘mule’ test prototypes. Two V12-powered prototypes were also built, probably in Germany, and inevitably the motoring press got wind of them and published ‘scoop’ stories of the planned new V12 Range Rover. What the press did not pick up, however, was the darker side of the story: major engineering changes were going to be needed to give enough clearance around the big V12 engine and the front end of the vehicle would need an extra 153mm (6in) of length ahead of the axle to maintain crash safety.

Over the summer of 1996, a Lifetime Planning exercise reviewed plans for the future of the existing Range Rover, and BMW concluded that the cost of the proposed 1999 model-year changes was excessive. Reitzle also believed that the result was still not going to meet his expectations, so he scrapped the 1999 model-year plans and told the Land Rover engineers that he would spend the money on an all-new Range Rover instead. This would bring a freshness to the model that could not be achieved through the planned facelift and it would put the Range Rover a further step ahead of its rivals. As a result, the 1999 model-year facelift was formally cancelled in September 1996; Land Rover was instructed to upgrade the existing model as best it could on a limited budget; and BMW began to focus on the all-new Range Rover.

UNDER CONTROL

Characteristically, Reitzle already had his own ideas: he wanted to build the new Range Rover on the platform that BMW had already developed for its E53 project. So Land Rover scrambled a team of four people to Munich to look at the feasibility of doing this. David Sneath was sent as the engineer, Don Wyatt as the designer (the job that was once known as stylist), Alastair Patrick was the manufacturing representative, and Paul Ferraiolo was the marketing man.

Don Wyatt oversaw L30 from start to finish in the Design Studio.

At this stage, the E53 project had been mothballed; after buying Land Rover, BMW was in two minds about the need to have a Sports Utility Vehicle (SUV) type of product in its range. Some of the early prototypes were brought out for the Land Rover team to look at, including one that did have real off-road ability, but it soon became apparent that the E53 platform was simply not up to the job. Sneath discovered that the driveshafts, differentials and aluminium suspension arms were nowhere near strong enough for the punishment a Range Rover would be expected to take off-road.

There was a certain amount of scepticism at BMW about this result, so as a next stage the four Land Rover people had to prove their point by writing a very detailed paper about what was necessary in a Range Rover. ‘It was the whole DNA of the vehicle,’ David Sneath remembered later, ‘the customer expectations as well as the engineering.’

Once BMW had seen this, the Land Rover team was asked to prepare a full Programme Investigation paper. There was some BMW input into this and the Land Rover team found themselves having to justify all kinds of assumptions that they had always taken for granted. Sometimes, they discovered that their assumptions did not hold up; sometimes, BMW had to give ground. In the end, the paper was approved. Land Rover had made its case for a standalone Range Rover project.

Nevertheless, BMW still intended to keep tight control over development of the new Range Rover. It had agreed that the earliest stages should take place in Germany, because the Rover Group’s engineering headquarters at Gaydon in Warwickshire was already working on several other major projects, and the company appointed its own Programme Director for what was christened the L30 project. This was Wolfgang Berger, who had been Reitzle’s right-hand man in the Rover Group and had come to understand the British way of working. The project code was simply part of a new system that BMW set up for its Land Rover subsidiary and is explained in the sidebar opposite.

All four members of the original team that Land Rover had sent out remained involved with L30 and David Sneath found himself having to pick the engineers he wanted from the UK. There were eventually eighty British staff on the team, each one shadowed by a German opposite number. In the end, there were 300 people working on project L30. Their project office was set up in a disused BMW power-train building in Munich; some British members of the team chose to move to Germany, while others, like Sneath himself, commuted home to the UK at weekends.

One of the earliest tasks that Sneath identified was that of educating the BMW engineers in what Land Rover was all about. Off-road driving is illegal in Germany, ‘and they just didn’t have the experience of it’, he explained later. So he found a forested estate on the Czech border and rented it for a three-week period. BMW engineers were invited along for a series of off-road demonstrations with existing Land Rover products to show just what a Land Rover – and by extension a Range Rover – was expected to do, and why BMW’s own E53 platform would not fit the bill. ‘Then they understood!’ he recalled with a smile.

It must have been at about this time that BMW shipped an E53 prototype across to the UK with the intention of putting it through some off-road testing at Land Rover’s Eastnor Castle test ground. Demonstrations Manager Roger Crathorne was allocated to help out and he remembers the E53 arriving in a covered truck. With it was the E53 project leader, Gerhard Boeschel, and Crathorne decided to take him round the test sites first in one of Solihull’s products. When they had finished, Boeschel turned to Crathorne and said that he was not even going to bother to get the E53 out of the truck, because it was not engineered to do the kind of thing he had just seen!

Nevertheless, the Land Rover engineers who worked on L30 were unanimous...