![]()

1 ‘As a practical object it will be profitable’:

Design, Industry and Internationalization from the Tokugawa to the Meiji Periods

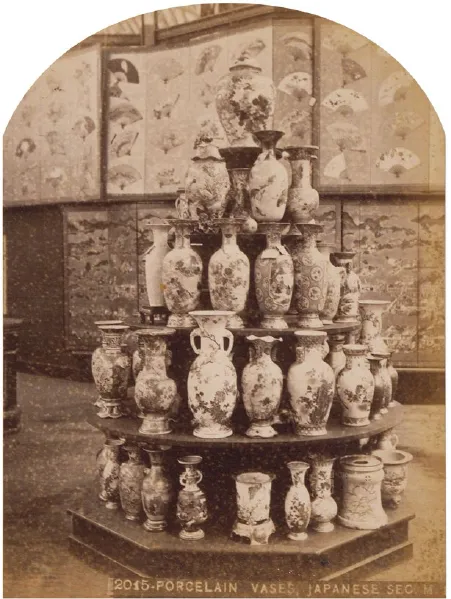

In 1876, dozens of porcelain vases from Japan went on display in Philadelphia. A sepia stereoscopic photograph cannot convey the exuberant decoration, the vases overglazed with colourful motifs and pictorial scenes and encrusted with moulded porcelain plants and animals. Tall bodies swelled under narrow necks before blossoming into wide mouths with extravagantly fluted edges. Vivid palettes – complex pictorial imagery and vegetal patterns rendered in red, green, yellow, black and white, with touches of pink, brown and blue – offered further visual stimulation, especially in the densely packed display. A high level of skill was required to create these objects: to fire them without collapse or warping; to maintain the circular form and symmetry, particularly of the fluted necks; to paint the intricate patterns and images; and to fire the different glazes so neatly, including multiple firings at different temperatures. Together, they appear visually compelling and extremely worked. In the juxtaposition of colours, imagery and impressive scale and form, they invite questions about the different elements and the vases’ manufacture.

The vases were designed and made in Arita, a porcelain district in western Japan. Arita had developed as the leading Japanese porcelain district in the early seventeenth century, possibly with Korean artisans kidnapped during Japan’s then national leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s invasion of the Korean peninsula in 1697.1 The kilns were moved to Arita, in the Hizen domain, to prevent rapid deforestation for kiln firewood in their previous location. In the seventeenth century, Arita developed a specialized industry in highly decorative overglaze porcelains, versatile in Chinese motifs, forms and colours. Their hybrid East Asian style, adapted for European tastes and interiors, allowed them to find a strong market in Europe, along with other kilns in the Hizen domain. Thus, Hizen porcelains had been a desirable luxury for wealthy Europeans for three centuries, competing in the porcelain market with the Chinese and French. In other words, by 1876 Arita makers had already been producing products for a similar market for some generations. Now, by combining their existing design elements in new ways, they were again drawing on available skills, materials, tools, techniques and infrastructure to accommodate their clients’ assessment of market demand and tastes.

Porcelain vases displayed in front of painted screens, stereoview of the Japanese section, Main Building, Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia, 1876.

The vases were exhibition pieces, made specifically for display at an international exposition to capture the attention and imagination of masses of foreign viewers – not only Americans but the international press and many international visitors. The vases were commissioned by the Japanese government to form part of the Japanese national display at the Centennial Exposition, held to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of American independence. Exhibition commissioners, appointed from within government departments with a European adviser, established criteria to help the Japanese exhibit win prizes and gain international acclaim for the sophisticated nature of what Japan could manufacture, represented here by products from Japan’s highly developed crafts industries.2 The display comprised hundreds of decorative objects, not least the folding screens (byōbu) with patterns of fans and gold-leafed cityscapes that sat immediately behind the plinths. Within the exhibition hall, it competed with similar displays stuffed with highly visual exhibition pieces, all following a standard aesthetic logic and vying with each other for visitor attention.3

In this context, design decisions conformed to international ideas, commonly shared among successful Western exhibitors, of what made a good exposition piece: the items were showy, visually complex and massed together at impressive scale in their display. They also combined multiple visual and formal standards associated overseas with Japanese export ceramics of the previous three centuries – including some adopted from Chinese ceramics. The difference between Japanese and Chinese motifs and style and the particular metaphorical, literary or historical associations of each decorative element would be well understood by some Japanese viewers, but for American and other viewers in Philadelphia would likely have created an effect of Far Eastern exotica. At the same time, sets of large decorative vases – imported from China or Japan, or fired in France – had been an established trend in European luxury interiors since the eighteenth century, and were adopted in the United States as well. The vases offered an already familiar object – one associated with foreignness, with the foreignness and exoticness visually amplified for visitor impact.

Dish for export, 1690–1720, porcelain decorated in underglaze blue and overglaze enamels, diameter 31.4 cm, Arita kilns.

Close examination of any object will reveal the coexistence of local practices and wider connections, both old and new, as an indication of broader historical change and continuity. In this sense, the vases present several key aspects of design and making in mid-nineteenth-century Japan. In 1868, after decades of domestic instability and new foreign pressures, Japan gained a new national government. During the Tokugawa period (1615–1868), the government had attempted to control foreign trade and diplomacy, in part to maintain domestic political stability. The new Meiji government saw increased engagement as inevitable but wanted to retain sovereignty over foreign powers’ interactions with Japan. Stronger projection of Japan’s image to foreign powers was part of its strategy for accomplishing this. This decision would have profound effects. As the vases suggest, much of its impact was in how people modified their existing resources and arrangements to accommodate the economic and material changes that followed this decision.

This chapter explores the impact of political and economic change in mid- and late nineteenth-century Japan on design and related industries, activities and products. The chapter begins with an overview of design and making in the Tokugawa period to understand the conventions and industries in place. This means treading familiar ground for readers acquainted with early modern and modern Japanese history, particularly the histories of consumption, technology and exhibitions. It then focuses on specific design initiatives launched in direct response to historical events. Their initiators included local politicians and entrepreneurs concerned to mitigate the impact of global events on their own communities; civil servants charged with curating Japan’s participation in international expositions; intellectuals interested in articulating Japan’s national identity during this time; educators who saw improved design as a way to help manufacturing communities weather change; and designer-makers, themselves concerned to maintain viability. The chapter discusses design practice and products in relation to these ideas and demonstrates how Japan’s existing design and making practices adapted to political, economic and material change in the Meiji period (1868–1912).

A principal takeaway from the chapter is the sheer heterogeneity of ideas already in circulation before the emergence of standardized mechanisms and institutions for design promotion. Post-war Japanese design is associated internationally with a strong national design policy and with the central government commitment to design promotion this entails. This was hardly the case in the nineteenth century. As we will see, while makers and their local supporters had recognized the importance of ‘good design’ in capturing public imagination and market share for several centuries, it would take the successes and failures of product exports for the national government to identify design as relevant for the national good. Chapter Two onwards will trace the arc of a specific set of policies, themselves derived from particular ideas about the power of design. Some policies originated with people in government – national, regional and local – who saw promoting design as a way to support economic development and improve lives. Others came from the commercial world, from entrepreneurs who saw design as a way for firms – and by extension national and local economies – to become more competitive. In this chapter, no such centralized vision or will describes design in the Meiji period. The chapter articulates how different groups of people, all invested in design in some way, thought that design, as a conscious intervention into the making of commodities, could help someone – individuals, communities, regions, even the Japanese nation – thrive during this period. It argues that all of these groups saw design as a mechanism for supporting industries and communities to weather change, and that some also saw design as a lever that could accelerate change. It suggests that these interventions and attitudes were less powerful, ultimately, in shaping design practice, let alone its products or consumer demand, than some had hoped. State intervention impacted some aspects of crafts industries, but other aspects – and some industries – were largely untouched by reforms. These aspects were shaped, the chapter argues, by larger historical developments and by designer-makers’ and users’ responses to them.

Design and Making in Early Modern Japan

With their riotous juxtaposition of colour, style and motif, the Arita vases indicate the depth of Japanese design skill, technological ability and market maturity in place before the Meiji period. Japan in the mid-nineteenth century was a sophisticated early modern society with a developed market economy, social structures and cultural production.4 In the centralized political system known as the bakuhan, the shogunate passed patrilineally through the ruling family. The Tokugawa bakufu oversaw the country from its base in Edo (present-day Tokyo), while the imperial family, formerly the nation’s rulers, remained in Kyoto, with the emperor a nominal figurehead only. Hereditary lords known as daimyō oversaw each domain or han, with an additional civil service infrastructure. Each province was responsible for an annual financial contribution to the bakufu’s coffers, generated by a tax on households. As we will see, this led whole villages and regions to develop cottage industries to procure this much-needed income. Interregional competition between daimyō became another driver of innovation, as daimyō supported the development of local industries and acquisition of imported technical knowledge to increase profits and prestige.5 Daimyō were required to maintain a full residence in Edo, where their families lived permanently, in addition to the provincial seat, and to spend one of every two years in Edo.6 This system spurred the development of road infrastructure from regions to the capital, as well as land and sea shipping routes for industrial and agricultural products. It also helped the regime to maintain power over the daimyō by depleting their finances – in addition to two households, daimyō were expected to travel in lavish processions and live well, extending their patronage to luxury goods producers.

The bakuhan dictated a formal status hierarchy. Below daimyo were samurai, followed by farmers, artisans and merchants, with ‘untouchables’ and some other groups outside. The behaviour, dress, residential location and occupations of each status group were prescribed by law. For example, sumptuary laws passed in 1628 limited peasants to garments of asa (hemp and ramie) and cotton, while allowing village heads to wear silk.7 A flurry of laws passed in 1683 included at least seven restrictions on townspeople’s clothing, including on embroidery, thin silk crepe and dappled tie-dye.8 The social status system was highly prescriptive but also flouted, particularly as by the nineteenth century wealth distribution no longer mapped onto social structure.9 As the Tokugawa period went on, people also began taking on roles and activities outside those prescribed. An annual provincial rice tax, levied on villages and converted into currency on the commodity market in Osaka, the nation’s finance and trading centre, supported the operations of the bakufu, the domains and the samurai (who undertook a variety of activities, including serving the Tokugawa and domain governments). Commerce made many merchants wealthy, especially in Osaka, leading to new fashions as merchant households found ways to circumvent the sumptuary restrictions. Farmers were expected to make their living from agriculture, but the tax burden prompted households and villages to develop secondary industries, both to produce goods for their own needs and to earn additional income by making products for urban markets.10 Indeed, a proto-industrial economy developed in many farming villages, with local entrepreneurs, sometimes the village headman, serving as middlemen between urban distributors and farming households.11

Entire villages and regions began to incorporate part-time industrial production into household activities, as farmers discovered that manufacturing – particularly of textiles – could supplant insufficient income from fickle crops. Village production could be divided into two types of goods: those manufactured for local use, within the household or village, and those manufactured for redistribution around Japan. The latter were supplemental for many farm households and served as cottage industries, with products made by hand in the evenings and winters; local merchants contracted with households in a ‘putting-out’ system, bringing them the raw materials and later purchasing the finished goods to pass on to a wholesaler or directly to shops.12 Some regions went one step further and established specialized workshops where farm women especially would work to gain extra income. In some cases, these went as far as...