![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Two hundred and twenty-four years ago, in 1798, Thomas Robert Malthus visualised that the population will grow geometrically twofold in every twenty-five years, and food production will grow only in arithmetic proportion that would result in famine and starvation. In other words, Malthus emphasised over two centuries ago that population control is important even when the population at the global level was not at all a problem. According to Malthus, ‘Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio.’1 The global population growth was very low and it seems that it took several centuries to reach the one-billion mark.2 According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, until the early nineteenth century, the global population was less than 0.8 billion. In the subsequent years, the population has increased gradually and took about 100 years to reach two billion.3 Since then, the global population growth has increased remarkably. Since the mid-twentieth century, the world population has increased remarkably from 2.54 billion in 1950 to 6.15 billion in 2000, and it is expected to grow to 9.77 billion in 2050 and 11.18 billion in 2100.4 In other words, 83 million are added every year, which indicates a 1.1 per cent growth rate per year.

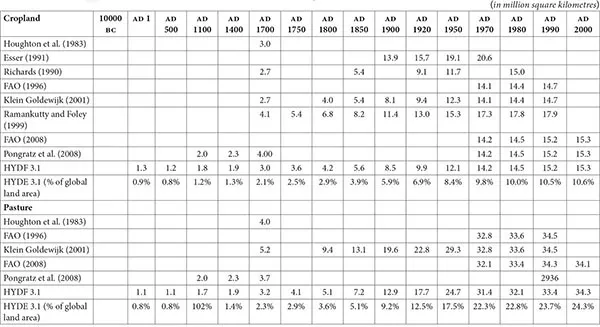

Due to the population growth, more areas were brought under cultivation and the total cultivated area has increased manyfold during the last three centuries. According to Goldewijk et al. (2010), the total cropland area has increased more than fivefold, i.e., 3 million square kilometres to 15.32 million square kilometres during the last three centuries.5 From

AD 1 to AD 2000, various estimates of the cropland at the global level show that they have increased remarkably. These estimates further indicate that from AD 1 to AD 1400, 1.9 to 2.3 million square kilometres of land was classified as cropland. In other words, over the fourteen centuries, the cropland has increased only marginally. Beginning with the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries, the cropland has increased gradually from 2.7–4.1 million square kilometres in 1700 to 4.0–6.8 million square kilometres in 1800, according to different estimates.6

Since the mid-nineteenth century, the cropland has increased remarkably (Table 1.1). In fact, croplands have increased two to three folds within one and a half centuries (1850–2000). Until the fourteenth century, less than 2 per cent of the world’s total geographical area comprised croplands which has increased marginally in the subsequent four centuries to 2.9 per cent. Since the mid-nineteenth century until the twentieth century, the cropland area has increased more than twofold. The pastoral land also varied until the fourteenth century and has marginally increased till the mid-nineteenth century. Thereafter, it has increased four to five folds in the subsequent one and a half centuries. Precisely, both croplands and pastoral lands were very negligible until the fourteenth century and have only marginally increased in the mid-nineteenth century and in the subsequent one and half centuries they increased several folds (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Global Cropland and Pasture Estimates for 10000 BC to AD 2000, Different Studies

Source: ‘The HYDE 3.1 Spatially Explicit Database of Human Induced Global Land Use Change over the Past 12,000 Years’, in Global Ecology and Biogeography: A Journal of Macro Ecology.

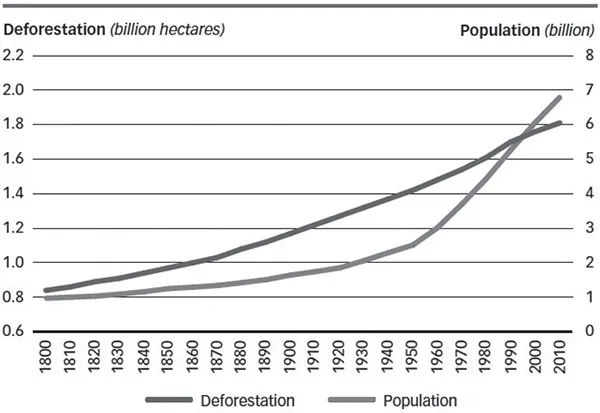

The increasing trend of croplands and pastoral lands indicates that more than fourfold common property resources have been brought under cultivation. The world population has increased gradually from 1800 to 1900 and after that there was a phenomenal growth, whereas deforestation occurred gradually from the early nineteenth century at the global level. This trend was depicted in Figure 1.1 which will give us a clear picture regarding the population growth and deforestation over two centuries at the global level.

Figure 1.1: World Population and Cumulative Deforestation, 1800–2010

Source: State of the World’s Forests Report 2012.7

Growing population has a direct impact on forests and the environment. When the population growth was low, deforestation was also low and as the population increased, deforestation has also increased. However, in the early days, people have used forest resources only to a limited extent. ‘People began converting forests to other land uses—using fire, primitive tools and grazing—thousands of years ago to facilitate hunting and agriculture.’8 Consequently, there was no serious threat for the forest resources. According to Michael Williams:

[T]he long-held view has been that prehistoric peoples were a nonfactor in environmental change and degradation. Their number and densities were too low to bring about significant change; their technology was insufficient to cause alteration; and their livelihood (particularly that of non-Western ‘primitive’ peoples) was in perfect harmony with nature.9

State of the World’s Forests Report 2012 mentions:

Conservation of forests formed an integral part of the Vedic tradition of India: as early as 300 bce, the Maurya kingdom recognized the importance of forests, and the first emperor of the dynasty, Chandragupta, appointed an officer to look after the forests. The concept of sacred groves is deeply ingrained in Indian religious beliefs, and thousands of such protected areas still conserve trees and biodiversity.10

However, population increase had led to an increased demand for cropland and grazing pastures over the period. According to FAO:

Some estimates suggest that global forest area has decreased by around 1.8 billion hectares in the past 5000 years (a decline equivalent to nearly 50 percent of the total forest area today). Archaeological and historical evidence indicates that much of this forest loss was associated with population increase and demand for land for crops and grazing, as well as with unsustainable levels of exploitation of forest resources.11

Population growth and deforestation occurred in different countries at different points of time. For example, in China, forest cover has declined rapidly over the past few centuries. ‘Four thousand years ago, the population of China was about 1.4 million people, and forests covered more than 60 percent of the land area. By 1840, China’s population had reached 413 million and forest cover had declined to 17 percent.’12 In addition to the population growth, colonisation has also made serious impact on the forest. For example, the forest cover declined in South Asia over several centuries and it was further accentuated due to the colonisation process. State of the World’s Forests Report 2016 states:

The forests of southern Asia were also converted to agricultural land to support the rapidly expanding population in that region. It is likely that the forest area in southern Asia has declined by more than half in the last 500 years. There, as elsewhere, colonization had an impact on forests, with the European colonizers heavily exploiting timber for use in other parts of the world. […] In the Americas, there is evidence that native cultures systematically used fire to convert forest areas for crop-growing or as a wildlife management tool. Large-scale forest conversion in the North American continent began, however, with the arrival of Europeans in the late fifteenth century. The rate of forest conversion rose sharply as the human population grew; on the other hand, the push westward by settlers in the nineteenth century led to forest re-growth on abandoned agricultural land in the east. In Central and South America, forest cover was probably about 75 percent of the land area before the arrival of Europeans; deforestation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries reduced this to about 70 percent by the early twentieth century.13

Historically different countries experienced deforestation either due to population or colonisation or both at different points of time.

Due to the population growth, the vegetated lands are converted for the croplands and pastoral lands and it has impacted the ecology and environment. William points out in Deforesting the Earth that:

As the forest changed, so the humans colonized the newly vegetated land with remarkable rapidity, doing all those things that humans do: foraging, firing, hunting, selecting species and rejecting others, turning the soil, fertilizing it, trampling it, and mixing it. In the course of manipulation, of the biota some tree taxa moved, flourished, or were eliminated, just as surely as if they had been affected by changing climate.14

This impact was much more severe after the industrialisation and technological advancement. Williams further states that the industrialisation, mechanisation, power; population growth and migration, colonisation and improvements in transportation and communication are the major driving forces for the deforestation process across the world from the eighteenth century onwards.15

After the Second World War, majority of the colonised countries got freedom. However, these countries continued to follow the same old colonial forest policies. ‘Although colonialism was largely dismantled in the aftermath of the Second World War, the forest policies of many newly independent countries in the tropics continued to reflect its legacy.’16 ‘Today, humankind has greater technological capacity than ever before to bring about rapid land–use change on a very large scale.’17 At the same time, several countries have experienced either stable or an increase in the forest cover during the second half of the twentieth century. The State of the World’s Forests Report 2016 also states that:

Forest area has been stable in North America since the early twentieth century, following two centuries of deforestation. Although forest cover in China had fallen to a historical low of less than 10 percent of the land area by 1949, it had recovered to nearly 20 percent of the land area by the end of the twentieth century as a result of major reforestation and afforestation programmes.18

Since the early nineteenth century, the population has increased marginally but deforestation occurred much more rapidly during the same period. In other words, in little more than two centuries, about one billion hectares of deforestation has occurred.19 It seems that until the mid-twentieth century, the deforestation of the temperate forest was high and after that, deforestation of tropical forest has increased rapidly.20

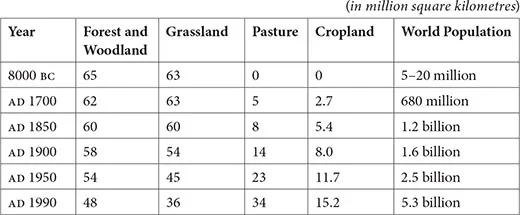

Decline of the forest area was also rampant in recent years, particularly from the last decade of the twentieth century to first one and a half decades of the early twenty-first centuries21 (Table 1.2). ‘In 1990 the world had 4,128 million ha of forest; by 2015 this area had decreased to 3,999 million ha. Thus, there is a considerable change from 31.6 percent of global land area in 1990 to 30.6 percent in 2015.’22 FAO states:

Over the past 25 years the world’s forest area has declined from 4.1 billion ha to just under 4 billion ha, a decrease of 3.1 percent. The rate of global forest area net loss has slowed by more than 50 percent between the periods of 1990–2000 and 2010–2015.23

Table 1.2: Trend of Global Population and Land-Use Pattern, 1800 BC to AD 1990

Source: ‘Population and the Natural Environment: Trends and Challenges’, in Population and Development Review by J.R. McNeill.29

According to the FAO, within fifteen years (1980–1995), the net decline in forest cover was about 180 million acres. However, this trend was not common among the different regions. It seems that the declining trend was mainly confined to developing countries as against the developed countries which were showing a net increase within the fifteen years.24 However, the forest area has declined at the global level in recent decades. ‘The geographical distribution of deforestation has changed in the twentieth century, but its major...