![]()

1

Outside looking in

On a fine morning in the first weeks of the Covid-19 pandemic, I ran into my former publisher, Ursula Owen, co-founder of Virago Press, by a local bus stop. It wasn’t clear if we were self-isolating yet or not, so we spoke to each other from a safe distance on the pavement – two militant feminists, now surprised to find ourselves in our eighties. In this disorienting new world of imminent confinement, our encounter felt like one between ghosts wandering around Limbo.

To my amazement, Ursula said: ‘I’ve been rereading Mirror Writing. It’s so good – I think it was before its time. It really should be republished.’

I was too touched to think of a generous reply – for example, I could have thanked her for publishing the book in the first place, but I was too startled to be polite. Instead, we exchanged anxieties about our health, the state of the world and the incompetence of the government.

Mirror Writing was published in 1982. It was a kind of autobiography, an account of that period of my life when I was preoccupied with the creation of a gay persona. I later came to have reservations about the book’s very camp approach, not because I repudiated camp, but because camp comes with its own problems. It operates as a defence against hostility and hurt, twisting trauma into a joke. My defiant lesbian identity was also protective; like a camp pose, it warded off pain, doubt and ambivalence.

Mirror Writing was a hybrid, because, in a further defensive move, I used my own experience to propel me beyond the personal into an analysis of autobiography as a genre of writing – since, after all, intellectual analysis, like jokes and defiance, is yet another form of defence, keeping emotion safely at arm’s length. So – like many autobiographies, I suspect – Mirror Writing was a fiction as well as a hybrid. It was a work of disavowal, neutralizing traumatic aspects of my childhood and its legacy of self-doubt and rejection.

Camp, then, is defensive, yet, in spite of my reservations, Unfolding My Past does, like Mirror Writing, recall the past in a spirit of camp humour. Camp is a satirical posture, tinged with black. As an attitude that originally arose as a defence against oppression, it has the power to demystify pomposity and self-importance, while at the same time being quite forgiving. Camp positions itself as an artificial attitude to life, or rather it exposes and celebrates culture as inherently artificial. Artificiality is often posed as being morally inferior to ‘the natural’, but I shall be defending the artifice of fashion and the other cultural forms that I researched.

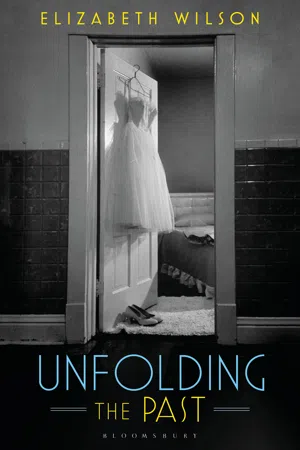

I return to life writing to explore what might be called the autobiography of my research. I see this as an unfolding, in the way that the arrival of a new garment in its outer casement is a moment of anticipation before you open the box, turn back the tissue paper that wraps the dress, lift it out and unfold it. That unfolding is only the start of a relationship, which begins as the dress or jacket adjusts itself to the wearer’s body and develops, as the garment becomes familiar, is worn and at length becomes well worn, by which time experiences and memories are captured in its folds and it has become part of your life and part of your personality.

The unfolding of a dress also provides a metaphor for my relationship with my work, my writing, the cloth of which is woven out of my life. By this I mean to suggest that the subjects I wrote about over several decades were as much a reflection of my inner life and personal history as a search for objective knowledge. My work was also underwritten by a politics, the embers of which persist today.

In the decades between the 1980s and now, literature has expanded into forms that Mirror Writing did, perhaps in a small way, anticipate. There were other outliers, among them Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights, a short work somewhere between fiction and autobiography. In it she wrote of her life at one remove, as I later did of mine, approaching the pain of her separation from her husband, the poet, Robert Lowell, obliquely, through stories of women and men she had known. She wrote of their emotional trauma rather than directly of her own. That, at any rate, is how I understood Sleepless Nights.

Since the last decade of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, distinctions between fiction and autobiography and even the boundary between academic and personal writing have begun to break down. Such distinctions were never entirely rigid, but genres have become more porous as the author has evolved into an ambiguous figure and writing into an act of self-creation more ambitious – and yet also perhaps more limited – than the recreation of an objective world. Novelists and historians continue to describe large events, but it is impossible for a writer today to present the panorama of a whole society in quite the magisterial way that nineteenth-century novelists were able to do. The omnipotent narrator may still exist but has become a less familiar figure. Individualism has swelled. Readers and writers yearn to interrogate their own feelings and vicariously experience the inner lives of others. The subjectivity of a single consciousness is a more feasible subject than a social panorama, when a global world in turmoil seems too vast to be reduced to one coherent narrative, no matter how all-embracing. Ideas and politics are more swayed than ever by the power of the personal – although readers and writers still do seek, of course, to understand the world objectively.

My first published writings were political forays into the ‘underground’ press in the effervescent years of the Miss World demonstration, Gay Liberation and left-wing militancy, yet within a surprisingly short time I published my first – academic – book, a critique of the institutional sexism of the welfare state. I considered myself to be a polemicist and almost at once began to feel uneasy about the label of academic writer. I struggled to escape from it, because I felt it cordoned me off in a non-literary writing zone, restricted to abstract thought. I was always trying to establish a foothold on more expansive and promising territory. I searched for some non-existent genre, for some literary peninsula, or at least an atoll, from which I could launch ideas in the context of personal experience rather than, or as well as, disembodied theory, or at least could anchor in daily life ideas that might otherwise have seemed remote. They would be more accessible, I believed, in the context of lived reality.

I had started out as a political writer, but in this search for ‘everyday life’ – or rather, some different way of writing about it – I found myself abandoning more con ventionally political subjects such as social policy. I moved instead into the research of consumption and the surfaces of life, fashion, spectacle and entertainment, urban social life, countercultures, art, film and, more unexpectedly, sport. All these were theatres of performance and had their passions, their fans and their costumes. As my research into dress developed, the very fact that colleagues and comrades often reacted with surprise or disapproval to subject matter they considered trivial alerted me both to its inherent importance and to my own emotional engagement with it. As well as being a researcher, I was a fan.

Researchers often talk about being in love with and passionately devoted to their subject. Research involves emotional commitment; researchers are drawn to subjects that have meaning to them in terms of sensibility, childhood memory or obsession. Research is more than an intellectual pursuit, more than the detached gathering of data. A research project is, in the end, a kind of love affair – and sometimes a love–hate relationship.

Individual human histories reside in many research works, not least when oral history becomes part of collective memory. Material culture concerns itself with objects that also have their own autobiographies and research can also tell their stories. Memories cling to the folds of a dress or to the pattern on a plate. Objects represent past experience in a congealed form. When brought into conversation with history, they illuminate social and cultural practices and deepen our understanding of our own lives and the lives of others, past and present.

My research into fashion led me to counter-cultural or alternative dress, sometimes referred to as anti-fashion. I branched out further from that, to explore ‘bohemian’ lifestyles, anti-establishment cultures and the mad personalities that thrived in those eccentric circles. This research in turn directed me towards the great cities in which it was possible for them to exist. As I moved into these new areas of mass culture, I found a world consciously dedicated to the promotion of pleasure and excitement. The urban scene provided a stage for the display of ‘appearances’ and the costumed variety of social life. Dress was a key that unlocked this spectacle of modern life and the problematic consumer world in which we live.

Fashion was traditionally suspect, and still is, because it prioritized pleasure and was often associated with sexual display – although it is just as often concerned with rules and conformity. In fact, consumer society as a whole is devoted to the search for pleasure, yet always disavows mere gratification or ‘entertainment’, seeking to clothe its enjoyment in moralism. If it is ambivalent about fashion, that is because fashion betrays this unacknowledged truth.

Through the study of fashion, or rather, dress, I came to understand that love of fashion was in part a search for personal identity through aesthetic experience. Fashion was more than frivolity – was, in fact, the very opposite. The search for the right style of dress could devour an individual’s existence or a fashion faux pas cause, in extreme cases, murder. Less luridly, it was a search for authenticity.

The intensity it revealed went far beyond dress. It was found in the obsessive involvement of audiences and fans with sport, film, music and fiction. This was also a search for meaning, not through ordered reflection, but rather through kinetic cultural experience. When the Liverpool football manager, Bill Shankly, allegedly said: ‘you think football’s a matter of life and death? I can tell you it’s a lot more important than that’, he wasn’t joking. We know that sport is more than mere amusement and, for better or worse, it plays a much more significant role in the lives of many of its supporters than the politics that actually influences their existence. It may be less universally recognized that popular drama, films and stories play a similar role in fans’ lives. They can be props to self-esteem, sources of self-confidence, anti-depressants, obsessions, even sources of enlightenment.

As my work developed, I noticed that my investigation into pleasure linked what seemed to others to be diverse fields of research. I wanted to understand why spectacle, narrative and sport aroused such intense emotions in readers, viewers and participants. My research was about their search for meaning, expressed through aesthetic experience and was an attempt to understand this. But this attempt – which I never thought fully to explain – to find connections between diverse cultural experiences brought me up against another restricting aspect of academic writing, for, as publishing has expanded, marketing distinctions have been established and enforced. It is not only that academic writing has too often been separated off from literature, as if facts and truths could be divorced from the style in which they are expressed. Divisions into subjects have been established, and this frustrated me. My work appeared to extend into fields not thought of as being connected with one another in any way as I wandered off from social policy into dress history, urban studies and the analysis of film. For this promiscuity, academics from those ‘disciplines’ attacked me as an invader into their territory, and I myself worried that perhaps I was nothing more than an intellectual butterfly, flitting from subject to subject with no clear commitment to any particular one. I feared I was a dilettante who flouted lane discipline, a kind of intellectual drunk, weaving about while in charge (or not) of my vehicle. The annoying result in practical terms was that my books, on fashion, on urban life and on tennis, for example, were promoted and reviewed in different journals or different sections of magazines by different specialists, were to be found in different areas of bookshops and consequently had different readerships. Fashionistas were amazed to discover my fiction, sports writers derisive that I’d written about clothes.

In 2017, a Swedish industrialist I met in Stockholm suggested a different way of looking at it. My problem, he said, was that I suffered from ‘brand diffusion’. This was a flattering excuse, implying that it was only due to the extensive range of my interests that I wasn’t better known as a writer, but it was a fact that, to me, my work formed a coherent whole, and frustrating if no one would recognize that: for there is an organizing theme that unites my work and an underlying rationale in my eclecticism. Over and above that, I strove to be a ‘writer’ rather than an ‘academic’, though I was always haunted by the fear that I was simply a failed popularizer.

In considering my research work as a personal journey, I was inspired by a misremembered quote from George Devereux: ‘All research is a form of autobiography.’ I may have invented this, as I haven’t been able to trace it, but when I came to prepare these chapters, it seemed strikingly relevant. Devereux, an ethnologist, psychoanalyst and trained social scientist, challenged what he saw as the false objectivity of science. This was a daring position to take because the idea that research might be subjective challenged entrenched assumptions. As a rational quest for knowledge, research seeks solutions to problems and promotes the Enlightenment purpose of mastery over our conditions of life. In the current era of ‘fake news’, rational evidence is often scorned and paranoid rumours gain credibility, but I am not suggesting that all fa cts are relative or that there is no such thing as verifiable reality or truth. In exploring the personal element in research, I am not endorsing a slide into subjectivism. I am simply suggesting the stunningly obvious: that meaning is emotional as well as rational.

Devereux deployed psychoanalytic ideas in his anthropological work. He believed that there is ‘countertransference’ in research, just as in therapy. The patient projects onto his therapist feelings related to past experiences and conflicts; this is known as transference. Countertransference refers to the response of the therapist, whose own emotions are equally at play as s/he reacts to the patient. In a similar way, the feelings of the researcher for their subject necessarily colour the relationship. There is no one-way encounter: the active researcher investigating the passive object of research. A researcher’s personality and experience colour the perspective they bring to bear on their subject – and that subject may in turn alter the researcher’s views. The enterprise therefore includes elements of hidden autobiography and self-reflection.

Autobiography in a specific sense is an exploration of the way in which work and personal experience are imbricated – or perhaps entwined is a better word, or even entangled. In tracing the relationship between my personal experience and my choice of subjects to research, I have seen aspects of my life in a different light, have understood my parents differently (and unexpectedly) and have had to continually reassess what exactly I was doing. I see now how I was drawn to certain subjects because I felt I was and would always be an outsider. My mother’s sense of shame in being divorced cast a shadow over my lonely childhood as I inevitably absorbed her guilt and shame. Deeply affected by her sense of social failure and of being discarded and marginalized, I felt that I too was destined to be an exile from exciting worlds that were forever closed to me.

Mine may be an ambiguous form of life writing because it is not the simple exposure of a life. It approaches a life at one remove, through a different kind of lens. I wanted an audience to see life and what I wrote about through my eyes, rather than simply seeing me. Writing was my form of communication precisely because it was a screen as well as a lens. It was almost as if writing was more than the simple act of recording. It was the formaldeh...