eBook - ePub

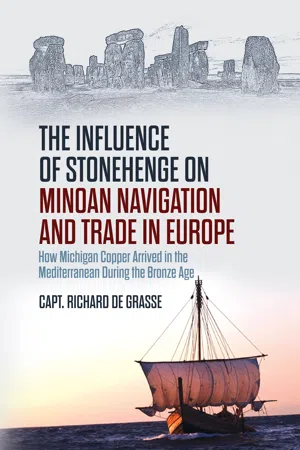

The Influence of Stonehenge on Minoan Navigation and Trade in Europe

How Michigan Copper Arrived in the Mediterranean During the Bronze Age

This is a test

- 114 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Influence of Stonehenge on Minoan Navigation and Trade in Europe

How Michigan Copper Arrived in the Mediterranean During the Bronze Age

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book presents a plausible account of how thousands of tons of unusually pure copper ore from Isle Royale in northern Michigan's Lake Superior was mined and shipped to Europe by the Minoans 4500 years ago during the Bronze Age, and how Stonehenge in E

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Influence of Stonehenge on Minoan Navigation and Trade in Europe by Richard V de Grasse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Ancient Navigation

With all due respect to archeologists and historians who have studied and reported on what we know of the Bronze Age period, as an engineer and ocean navigator I see history through the eyes of a mariner. That’s why when I reviewed the timeline of navigational history during the past 4500 years, I was astonished at the nearly 1500-year pause in navigational and cosmological achievements in Europe from the Roman Empire in 200 BC until European explorers, particularly Columbus, discovered the Bahamas. The Chinese and Polynesians were exploring the Pacific and the rest of the world hundreds of years before Columbus sailed the Atlantic. There is, however, no evidence that either the Chinese or the Polynesians were the Isle Royale miners. If it weren’t for the discovery of the vast copper deposits on Isle Royale in Lake Superior and the thirst for copper to make bronze—which is smelter of 90% copper and 10% tin- especially in Europe and the Mediterranean, the Minoans might never have learned basic ocean navigation and made the many copper voyages across the Atlantic.

Ivar Zapp and George Erikson wrote “Atlantis in America, Navigation of the Ancient World.” In it they reiterate the notion of the navigational Dark Ages during the Roman Empire beginning about 200 BC. They do question the Phoenicians predecessors. My response is the Minoans were the sea people and predecessors to the Phoenicians. Had the Minoans and their Crete-based fleet survived the volcanic destruction of their home on Thera the Phoenicians may never have become renowned world navigators and traders.

The Dark Ages was a period in history when Europe was governed primarily by Rome with the Catholic Church ruling over the advancements of science. Earth science, mathematics, astronomy and navigation did not advance significantly during this 1500-year period before Columbus. The study and reverence of celestial bodies was condemned by the reigning Church as idolatry. The Church and Rome itself directed all new discoveries, which were nearly all land-based. It wasn’t until about 1300 AD—after the magnetic compass was discovered by the Chinese- that the Catholic Church decided it was in its interest to spread the Gospel to the New World and began to endorse voyaging to the nearby Canary Islands in the Atlantic. Most of which can be reached by dead reckoning. Celestial navigation is not necessary to reach the Canary Island from the Gates of Hercules–Gibraltar. Dead reckoning is a basic navigational technique which uses a magnetic compass or some other means to determine ship’s heading, latitude, for example, along with the speed of the vessel toward its destination. To dead reckon from one place at sea to another, a navigator must accurately know his own starting position and the position (coordinates) of his destination.

Until about 1300 AD the Church had no knowledge of or interest in navigational science and seagoing discoveries. Europe had entered the Iron Age about 1200 BC and there was plenty of iron ore in Europe. The demand for copper to feed the Bronze Age diminished as the Iron Age began. Iron replaced bronze. Isle Royale copper mines were no longer needed and were abandoned around 1250 BC. The Church and Rome eventually came to believe the hundreds of stone circles were ceremonial and funerary cites created by local non-threatening factions—the Beaker People, Druids, Pagans and other religious sects. It’s clear neither the Church nor Rome delved into astronomical mathematics and earth science. They disregarded the celestial workings of the Babylonians recorded on hundreds of clay tablets. I conclude that there was a concurrent astronomical use of a number of stone circles, particularly Stonehenge.

To consider the question of concurrent stone circle use, discount the period after Christ was born and the subsequent evolution of the Roman Empire and the Catholic Church and look all the way back to the time of the Minoans and even the Egyptians, about 2500 BC. Many stone circles scattered around Europe, including Stonehenge, had significance and measurable importance to ocean navigators, seafaring traders and local communities 4500 years ago. Stone circle importance to celestial navigators was vital yet generally unrecognized by the general stone circle user population when compared with other more popular and conspicuous uses such as ceremonial and funerary activity, including, of course, seasonal planting and harvesting planning. Use of stone circles for celestial observations, particularly at Stonehenge, required knowledge and use of basic geometry not only for designing and building the stone circle, but particularly for celestial observations. Sight-taking geometry, techniques and devices necessary for accurate celestial observations were likely known only to a few stone circle astronomers and, I believe, ocean navigators. In fact, one can visualize the small group of mathematically-inclined, celestial sight takers working at the site virtually unnoticed by the multitude of the much larger and more ostentatious ceremonial and funerary gatherings.

Stonehenge was construction during the Bronze Age, nearly parallel in time with the building of the Egyptian pyramids between 3000 BC and 2000 BC. And since both were extraordinarily important engineering achievements of the age, I was interested in pyramid engineering. The building of the pyramids required somewhat different techniques and tools than Stonehenge, but a knowledge of basic geometry, physics and astronomy was necessary to build both. The Egyptian engineers needed to level and square every pyramid block. They even aligned the Giza pyramid to the celestial north. Likewise, Stonehenge engineers aligned the stones to various celestial events. I believe they had the time—hundreds of years between 2500 BC to 1250 BC—and the inclination to exchange engineering knowledge and techniques just as engineers do today. To me this means the knowledge of how the Egyptians were able to level and align each and every pyramid block could be applied to Stonehenge. Stonehenge builders and astronomers also used basic geometry and were able to build and align the stone megaliths and measure the altitude/angle of celestial bodies. I describe the methods and devices used by the Egyptians and how they were used at Stonehenge and other stone circles in Chapter 5, Celestial Observations and Navigation.

The Uluburun, Turkey Wreck

The cover shows the recent replica of the oldest shipwreck in the world. Close observers will note an inflatable dinghy tied along the port quarter of the replica. I made friends with Richard R. E. Burke the builder of the 21st century sea-going replica. By now I was convinced the Minoans were the forebears of the mythic heroes who sailed to Troy, the west coast of Europe and America. But until the structure and contents of the Uluburun wreck were carefully removed and analyzed, I lacked any physical evidence. I was afraid my stone circle thesis had run out. Then I heard about the Bronze Age wreck from several sources and quickly latched onto the data. To a sailor the Uluburun wreck counts as one of the greatest nautical archaeological discoveries ever made.

The wreck was found in 1982 untouched except by the sea, on the seabed off the Uluburun promontory on the south coast of Bodrum, Turkey. For centuries, the wreck lay undisturbed and protected from looters by 45 meters (147 feet) of sea water. Then in 1982 thousands of years after its last voyage, a sponge diver found it. Fortunately, the diver, Mehmet Cakir, realized the findings were significant and reported his discovery to Turkish authorities. The Turkish authorities made 22,000 dives during an astonishing eleven-year period to excavate the wreck. The remaining hull timbers were carbon dated to 1306 BC. They accomplished one of the most complete and thorough wreck recovery efforts ever made. The Turkish authorities built a complete and well-presented museum to house the artifacts in nearby Bodrum, Turkey. The Uluburun ship carried exquisitely wrought gold and silver jewelry and a cornucopia of rich fruits and spices, as well as huge amphorae from Lebanon; terebinth resin, used to create perfumes; ebony, which had come all the way from Egypt; and all manner of exotic goods like elephant tusks, hippopotamus teeth and ostrich and tortoise shells. The museum glass cases told a lot about the life of the elite during the Bronze Age. The wreck was a Bronze Age time capsule and provided convincing evidence of widespread trade utilizing sea-going vessels.

The wreck’s main cargo was in the hold: The raw materials for making bronze, even in the right proportions: 9 tons of copper to 1 ton of tin. There were 121 copper ‘bun’ ingots, together with another 9, and 354 copper ‘oxide’ ingots with an average weight of 23 kilos (50 pounds). Each copper oxide ingot was about a meter long with sharp corners. They are called oxhide ingots, because their distinctive shape is a bit like the hide of an ox when it has been flayed and stretched. Archaeologists think the distinctive shape was created for easy handling and smelting. They are likely right.

My plans are someday to visit the museum! I can report on the wreck because of the number of written reports, several video presentations, museum web page, and, of course, the sailing replica. Each time I read a report of the ship’s construction and an analysis of its contents, I kept waiting for either support or repudiation for my Stonehenge, stone circle, ocean navigation argument. For the first time in history, it was possible to connect Mediterranean shipbuilding, sailors and navigators to international navigation and trade. Because the contents of the wreck were so complete, and traceable to their origins, in Europe, Asia and even America, plus the vessel was likely built of Crete cypress. The vessel was well designed, constructed and made seaworthy, capable of ocean passage making. I then began to consider the needs of ocean navigators given the absence of aids to navigation, compasses, accurate time clocks, sight taking devices and detailed nautical charts.

Given that ocean navigators need a universal annual calendar, prime meridian—beginning of the day, level horizon and site for celestial observations useful aboard ships at sea. It was Gavin Menzies who concluded that the Callanish stone circle in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland was used primarily as an aid to navigation for Minoan copper ships transiting from Newfoundland across the Arctic Ocean to Scotland. If the Callanish stone circle was used as an aid to navigation why not Stonehenge and the others? How could they be used as aids to navigation?

The Bodrum museum has carefully assembled and displayed the 4300-year-old Bronze Age ship. Her charred timbers were carbon dated even though they were spindly and frail, ravaged by centuries of seawater. She was about 15 meters (50 feet) long, but from all reports and videos, she looked nimble, responsive, maneuverable and seaworthy. The ship was built of cedar in the ancient hull-first tradition, with pegged tenon joints securing planks to each other and then to the keel. To build her, a team of men would cut down a tall cypress tree, strip its bark, and carve the length into a keel. Crete was covered with cypress forests in the early Bronze Age; Cypress is ideal for shipbuilding because it expands in seawater making the seams watertight. Crete was not only the likely source of the cypress keel and planks; it was also the home port of Minoan sailors. It was evident from the diversity of the cargo that the ship had traveled extensively to ports throughout the Mediterranean, including ports in Egypt. The navigators aboard the ship certainly exchanged geometric and celestial observation techniques and devices usable for vessel navigation with local astronomers, engineers and navigators during their stops, particularly in Egypt during the building of the pyramids. They would also exchange details about the harbors and waterways, as sailors and navigators do today.

The ton of artifacts, DNA, and the Beaver Island stone circle and other traces of Minoan mining in the Great Lakes provided proof that it was the Minoans who carried out the mining operations between 2500 BC to 1250 BC. Gavin Menzies’ in his Lost Empire of Atlantis compares pictures of Minoan artifacts found on Isle Royale in the Great Lakes with those found throughout the Mediterranean, particularly aboard the Uluburun wreck. An analysis of the copper oxhides recovered from the wreck provided further evidence that Minoans were the Lake Superior miners. A number of American geologists agree that the Great Lakes copper was of extraordinary purity. Professor James B. Griffin of the University of Michigan puts the total trace elements in the material at 0.1% or less: Lake Superior copper is of 99% purity or greater. Copper during the Bronze Age was a very important commodity. European copper was not as plentiful or of the purity of the Great Lakes copper. Isle Royale copper in Lake Nipissing—the post Ice Age predecessor to Lake Superior, Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, was essentially free for the taking, local mine labor was likely cheaper than European mine labor. Isle Royale is a long, narrow 46-mile island. Its copper mines were spread the length of the island. The Isle Royale copper, termed “float” copper, was not as deeply buried as European copper and more easily moved and loaded aboard Minoan rafts or sailing craft tied alongside the island.

Several non-invasive X-ray spectrographic analyses were conducted measuring the trace elements in copper artifacts from Lake Superior and from the Uluburun wreck. The chemical characteristics of copper artifacts from a given location are exceedingly difficult to repeatably quantify with a less than 1% accuracy. The analyses done were thirty years apart. However, they essentially reached the same conclusion: The copper aboard the wreck was of 99.9% purity and Lake Superior copper is the only copper known to have of such purity. European copper is somewhat less pure and more difficult to mine, transport and load aboard ship. More on mining and shipping copper in Chapter 3. It’s very likely the copper oxhide shaped ingots found aboard the Uluburun wreck came from. Isle Royale. I am convinced that the evidence is clear as it ever will be: Minoans from Crete did indeed mine the copper in Lake Superior and made numerous ocean voyages to and from America during the Bronze Age. Accurate and safe navigation of their vessels was essential.

Minoan Miners and Navigators

No one, with the exception of contemporary authors Gavin Menzies, author of the 2012 book The Lost Empire of Atlantis, and Roger L. Jewell, author of the 2008 book Ancient Mines of Kitchi-Gummi put it all together: Isle Royale mine location, great quantity and purity of Isle Royale copper, the enormous market for Bronze Age copper in Europe, the Uluburun wreck, and the very limited Native American uses for copper. In fact, local native copper artifacts are few and far between. There is no evidence that the local natives knew of the copper-tin mix and the smelting process necessary to make bronze. Local uses came nowhere close to the thousands of tons of copper mined. Archeologists have looked, but they have found no trace of the immense quantity of copper mined in the Great Lakes, particularly on Isle Royale, or anywhere else in North America. Menzies and Jewell concluded that the miners were Minoan from Crete in the Mediterranean. The thousands of Minoan tools, weapons and implements recovered at the Isle Royale mines were nearly identical to Minoan artifacts on Crete. Gavin Menzies reported rare DNA haplogroups within local Great Lake population compared with DNA traces from Minoans of Crete. Pages 68–69 in Lost Empire of Atlantis.

Gavin Menzies was a 20th century submarine commander and navigator in the Royal Navy with whom I had corresponded. Unfortunately, he died in the spring of 2020. He became convinced, as I have, of possible water and land routes between Isle Royale and Crete during the Bronze Age. Roger Jewell also conceived of water routes to and from the Mediterranean. I’ve contacted both Gavin Menzies and Roger Jewell on several occasions. What intrigued me was a stone circle discovered on Beaver Island off Keweenaw Bay on the northern reaches of Lake Michigan. Civil Engineering Professor James Scherz at the nearby University of Wisconsin evaluated the large 121 meter (397 feet) diameter stone circle and concluded that it was built for astrometric purposes. Gavin Menzies expanded on Professor Scherz’s idea and concluded that the Beaver Island stone circle was used by Minoan navigators as an aid to navigation as they made their way north on Lake Nipissing (now Lake Michigan, Lake Superior and Lake Huron) toward the northwest waterway to Isle Royale. The Minoan navigators early on in their American mining operations determined the latitude of Beaver Island. They made celestial observations, likely using the sun and Polaris, on their way north on Lake Nipissing to reach the latitude of Beaver Island. Once at Beaver Island, they turned toward Lake Superior’s west end and sailed north and west to the latitude of Isle Royale and the copper mines. There was no indication that the Beaver Island stone circle had any ceremonial or funerary purpose. It was a stone circle used by the Minoan sailors as an aid to navigation to and from the mines on Isle Royale. The Beaver Island stone circle has not been maintained and several of the stones have fallen over.

Given what I’ve learned as an American navigator and read about Bronze Age navigators, their vessels and the trade in copper, I became convinced that Minoans were the Isle Royale miners, and they were the ones who made numerous voyages to and from the Mediterranean and Lake Superior over a period of nearly seven hundred years. Given what we know about the Minions regularly transporting tons of copper across the Atlantic Ocean between 2500 BC and 1250 BC in boats like the Uluburun wreck replica, I wrestled with the question: how did they do it, and were the hundreds of stone circles in England, Scotland, Wales and elsewhere on the east coast of Europe somehow utilized?

During the nearly seven hundred years the Minoan culture flourished, the Minoans made numerous trips back and forth between the Isle Royale copper mines in Lake Nipissing and the European and Mediterranean copper and bronze markets. Minoan artifacts at Isle Royale, DNA among the natives, seaworthy boats, the Bronze Age market for copper, the Uluburun, Turkey wreck, the numerous books and articles about the Isle Royale copper mines and all, are convincing evidence that the Minoans were the copper miners. I’m also convinced that the Minoans became the astro-navigators of the Bronze Age and that they had the knowledge, expertise, time, the will and the finances to improve ocean voyaging ability in an effort to increase trade in copper.

The Isle Royale Copper Voyages

As a United States Coast Guard veteran, small sailing boat trans-ocean sailor, navigator in the United States Power and Sail Squadron and a member of the respected United Kingdom based Ocean Cruising Club, I became very interested in the boats, seamanship and navigation of the ancient Minoan miners. Considering the evolution of navigation methodologies over the centuries, and the skilled navigators I have known, I believe that, given the several hundred years the Minoan trading empire flourished they were much more knowledgeable about the practice of navigation than we give them credit for. They had no compass, no mechanical or electrical clock, no detailed nautical charts, no weather reports, and no electronic communications. From what Gavin Menzies and Roger Jewell envisioned, the round trips took upwards of two to three years. Several months getting to the mines from their home base on Crete in the Mediterranean, couple of summers mining copper, winter months camped out at the mouth of the Pearl River at the lower Mississippi River, and a few months getting back home across the Atlantic. Given the thousands of tons of copper mined, the Minoans must have had many seaworthy vessels and made many trips involving hundreds of miners, sailors and support personnel.

Copper Currency

The Beaver Island stone circle in Lake Michigan and the stone circle on Callanish on Isle Lewis in the New Hebrides of Scotland, noted by Gavin Menzies, gave me another inkling. Because the copper mining operation was large...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Testimonials

- Foreword

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Name Index