This is a test

- 226 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

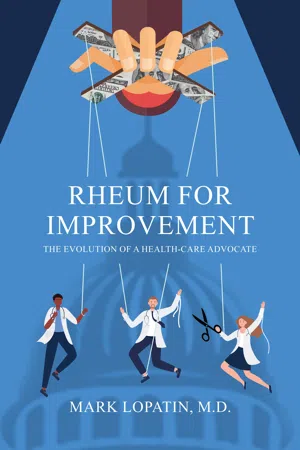

Rheum for Improvement is a physician's account of how corporate medicine has transformed health care from a human interaction between a patient and their physician into a business transaction between a consumer and a provider. It is also a personal story of how frivolous legal action triggered that physician to become an outspoken advocate for health-care reform. It will be of interest to anyone who interacts with our health-care system, but especially physicians, who must navigate bureaucratic obstacles on a daily basis.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Rheum for Improvement by Mark Lopatin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Teoría, práctica y referencia médicas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicinaPART I

EVOLUTION

Chapter 1

Beginnings

In the beginning, I was completely clueless. The year was 1975. The top movies that year were Jaws and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. “Love Will Keep Us Together” by Captain & Tennille was the top song, and gas was 57 cents per gallon. I was 18 years old but a very young 18 years old. I had just graduated high school in the top 1% of my class. I was book-smart but lacked life experience. Nerd, geek, dweeb—take your pick for the proper word that was applicable. The only job I had ever had was as a karate instructor, and I simply did not have the relationship skills necessary to be successful at teaching others. I had started karate lessons five years earlier at the insistence of my father after I had had the crap knocked out of me in a fight. It was the only fight I ever had.

I was a late bloomer. I only weighed 140 pounds when I graduated high school. My first girlfriend did not appear until after high school graduation, and she only lasted that summer, before we went to separate colleges. I was about to enter the University of Pennsylvania for pre-med.

I was oblivious to the world, having grown up in the amniotic fluid of a sheltered middle-class existence in the suburbs of Philadelphia. I remember being sent home early from first grade, but nothing else, on the day JFK was assassinated. The tumultuous events of 1968; the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the war in Vietnam, and racism as exemplified by George Wallace, barely registered on my radar as an 11-year-old. The Kent State shootings occurred in 1970, when I was 13 and did not move the needle for me. Even Watergate, a few years later, did not attract my interest or arouse my curiosity. In 1975, the war in Vietnam finally ended, but to me that did not matter because I knew very little about it anyway. I knew nothing of racism and politics. Although I am Jewish, I had never experienced anti-Semitism. I did not know the difference between a Democrat and a Republican, nor did I care. I would be able to vote for the first time in the 1976 election, but even having that privilege did not spark my interest. It would not be until the early 2000s that politics would register on my radar. I had no idea of what was going on in the world around me.

Growing up, my passions were sports, especially the four major Philadelphia sports teams. I played street hockey and football with the other kids in the neighborhood. I was an avid hockey fan. I cried when the Flyers missed the playoffs by four seconds at the end of the 1971–72 season. I played tennis and golf regularly with my dad. I knew the layout of Valley Forge golf course by heart. As a senior in high school, my classes were often done for the day by 11:30 a.m., and I would sneak on to Merion with a friend of mine to get in a few holes here or there. The Flyers had just won the Stanley Cup for the second time, and I kept a record of every game that season, listing the final score, goaltender, and losing team. Not surprisingly, my high school calculus teacher labeled me a “Flyers nut” when he signed my yearbook. I followed the rules and deferred to authority. Skipping school was unheard of for me, but somehow I found a way to assuage my guilt enough to attend the Flyers’ parades in 1974 and 1975. I was such a fan that my first year in college, I took it upon myself to visit Joe Watson, a Flyers defenseman, in a local hospital after he was injured. I can only imagine what he must have thought of this 18-year-old who showed up at his hospital room to meet him in person. It would not be the last time I presented myself to a complete stranger to achieve a goal.

Growing up, we had season tickets to the Eagles, first at Franklin Field and then Veterans Stadium, and I loved them despite their lack of success in the 1970s. In 1975, the Phillies were about to be good again. The 76ers told me that they owed me one. Sports was my focus.

I had no way of knowing in 1975 what the future would hold and the unexpected paths my life would take. There was no way to predict that I would become political, or that I would someday be leading a protest outside a local hospital carrying a sign advising patients that if they were sick, to call their lawyer, rather than their doctor. An AP photographer recorded the event and it was featured in Time and USA Today.

Nor did I know that I would be interviewed for a New York Times article3 criticizing how pharmacies operate, or that I would write numerous articles and/or op-eds for newspapers across Pennsylvania and in national physician blogs regarding our broken health-care system. I could not imagine that I would be asked to do national podcasts, addressing issues that compromise the care that patients receive. I could not foresee that I would serve first as president and then chairman of the board of my county medical society and also serve on the board of trustees for both the Pennsylvania Medical Society and their political action committee. I had no way to envision that I would be afforded the opportunity to speak at the Library of Congress or serve on the National Physicians Council for Healthcare Policy. I did not know that I would meet and communicate with many other physician advocates from across the country as well as many legislators. Social media was unimaginable at that time, and so was my ultimate future as an advocate for health-care reform. In 1975 that concept was beyond my realm of comprehension, with good reason.

At age 18, I viewed medicine as a noble profession. Doctors were highly respected in the community. Marcus Welby was an icon, appearing on television every Tuesday night to ease yet another patient’s suffering. There was no mention of the corruption that exists in health care. I had not yet learned that some physicians will say anything, even in a court of law, where the truth is required, or that lawyers could bring a case against you simply because you were a treating physician. It was a foreign idea to me that when the state board of medicine has an agenda, the facts of the case don’t really matter. It was truly a rude awakening for me when I experienced these realities.

I did not yet realize that many would find it acceptable for those without a medical license, medical degree, or medical training to be able to practice medicine, and that some corporate entities would even promote that. Abbreviations such as MOC, MACRA, MIPS, or PBMs were not yet part of my lingo. Scope of practice was a foreign concept. I could not conceive that I would one day testify in Washington, D.C., regarding the sham that maintenance of certification has become. I had no way to know that middlemen and bureaucrats would hijack health care for their own financial gains. There was an awful lot about practicing medicine that I had yet to learn or could even imagine. My ideals were about to be shattered!

At that time, I simply anticipated the wonderful feelings that come from helping people. I had no idea of forthcoming legal cases or that I would experience a form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of fraudulent testimony against me that threatened my career. I never considered the feelings of helplessness when a patient suffers and you can’t fix them; the introspection that comes when a patient is angry or upset with you; or the despair that sets in when you feel you may have actually done something that might have hurt someone else.

I was about to get schooling in more than just medicine. I was about to get an education in life and in myself that would take more than 40 years. It is still ongoing.

In 1975, I headed off to college armed with a letter from my older brother with life advice regarding the future. I continued to bask in the glow of my naiveté. While in college, I joined a fraternity. I got drunk for the first time in my life. I tried marijuana but never anything stronger. During my entire four years in college, I only had one girlfriend, and that was only for a total of two to three months. I watched a stacked Phillies team fail to win the pennant for three straight years from 1976 to 1978. I celebrated Hey Day and Skimmer Weekend at Penn each year. I “drank a highball” and “raised a toast to dear old Penn” at college football games. I watched Penn go to the NCAA final four in 1979. Mostly, however, I spent college taking science classes and studying in preparation for medical school.

During my sophomore year, I got a job working as a lab technician at Lankenau Hospital. This was my first occupational foray into the world of health care. One of my colleagues there later became my roommate in med school and a groomsman at my wedding. Saturday Night Live was all the rage, and with some friends, I made a movie detailing what would happen to Mr. Bill if he came to our lab to get his blood drawn. This was 1979. AIDS was unknown at the time, and we used real blood to illustrate Mr. Bill’s travails. The world was innocent, or to be more accurate, I was.

I applied to medical school and was accepted to one in Philly and one in Pittsburgh. Naturally, I chose to stay close to home and attended the Medical College of Pennsylvania (MCP). MCP initially was founded in 1850 as the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania and became known as the Women’s Medical College in 1867.4 It was the first medical school in the world authorized to award women the MD degree. It ultimately became co-ed in 1970 and was renamed the Medical College of Pennsylvania. It was not well known as an academic institute. Instead, its strength was in its diversity, attracting students who were more well-rounded rather than simply accepting those with the highest grades and highest scores on their Medical College Admission Test.

Medical school was a whole new world for me, but most of my memories of that time are superficial ones. The first two years were merely an extension of college, albeit with much more material to learn. Of course, I never dissected a cadaver in anatomy lab as an undergraduate. We had many lectures every day, and each day a different student was required to take notes on the material. These notes would then be submitted to the instructor for accuracy and then distributed to the rest of the class for their study purposes. During my second year I had the opportunity to be the note taker for the session on history and physical exam. I have always liked a good pun and even more so, a bad one. I therefore proceeded to describe in my notes that when you ask a patient multiple questions about the abdomen and they answer no to all of them, they are referred to as “an abdominal no-man.” The instructor at that time was the chief of medicine and he was not amused by my feeble attempt at humor. He was quite an intimidating figure to a second-year medical student. His response was to scrawl “NO” across my notes in large red letters. It was my first inkling that perhaps what I was doing should not be taken so lightheartedly. This man was a stickler for details, and he emphasized the commitment we needed to be making to medicine. As one example, he demanded that we do rectal exams on all patients admitted to the hospital, with the only two reasons for not doing so being no finger or no rectum. I did not appreciate him at that time. I thought him a curmudgeon with no sense of humor. Little did I realize the lesson he was teaching us in terms of being dedicated to our career path.

We played football or softball on the weekends. I was never much of a partier, although we sometimes would hit the local saloon after games, where I would slowly sip my one beer. I rarely finished it. When I was not studying, my outside life continued to revolve around sports. The year 1980 was a banner year for me, as all four Philadelphia sports teams went to the finals, with the Phillies winning the World Series. I had my first serious girlfriend, whom I had met at my brother’s wedding. I was beginning to mature, but only a little.

We did not really start to see patients until my third year, and this was in the hospital setting. I did not have patients that I considered my own, and therefore did not really form any type of long-term relationships with them. I remember the name of my first patient that I saw in the hospital, but nothing more about her.

We learned how to conduct a history and physical as well as the diagnosis and management of different diseases. I remember being taught the importance of obtaining a complete history, including a sexual history, and practicing this skill on my patients. When I asked one patient if she was sexually active, she responded with, “No, I just lie there.” Another patient must have thought he was Vanna White from Wheel of Fortune, as he reported trouble “moving his vowels.” Yes, patients do say some unexpected things.

Residency provided new opportunities. For my first rotation, I was sentenced to go to West Park Hospital. West Park was a local community hospital that did not have a great reputation for teaching. The house staff held little respect for the attending physicians there. They were community doctors rather than academic doctors, and in our minds as hotshot residents, they knew very little. I feel quite differently now that I have been a community rheumatologist for 28 years, but I did not know any better at the time. I complained to the director of our residency program about having to start my training there. I wanted to go to a more powerful affiliate hospital for my first rotation where I could learn more. She taught me a very valuable lesson by explaining that my education and my future depended much more on me than on where I did my rotations. This was something I to...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- PART I EVOLUTION

- PART II REVOLUTION

- PART III RESOLUTION

- Abbreviations

- References

- Acknowledgments