![]()

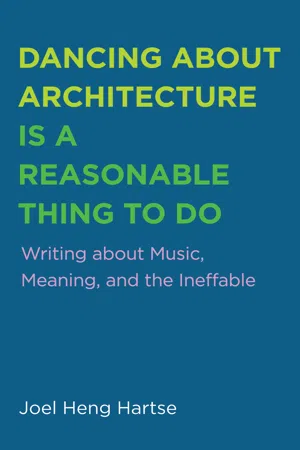

Attempts at Dancing about Architecture

The word “essay” comes from the French verb essayer, which means “to try” or “to attempt.” I don’t know if what I write about music truly counts as essays, because that word is so overused in my line of work (teaching writing to university students) that its meaning has become occluded, but I do regard the writing I’ve done about it over the last twenty years as attempts to pin down something elusive and ineffable. What follows here, then, are various essays—attempts—at dancing about architecture—on a variety of themes that are almost impossible to capture. I used to think language was the most important and valuable tool we had for making meaning, but after twenty years of writing about things that matter very much to me, I am no longer certain of this. When I look at these pieces, I am not always sure if what I meant to mean has been meant, as it were. But I have tried to write about some ineffable things here: hope, faith, loss, transcendence, and the self. These are things that feel very difficult to explain, but the best we can do is to try, and there can be an awful lot of joy in the trying. Like most of what I write, many of these pieces are concerned with the twin ineffables of music and religious faith, or even music and God: two things that seem very difficult to put words to, but that have always seemed, to me, worth trying to talk about as much as possible.

![]()

FAITH

One of my preoccupations as a writer-about-music has been what is called “Christian music.” (In fact, I wrote an entire book about it about ten years ago.) This is a genre, if it can be called one, that is produced by and for evangelical Christians, mainly, and it is a genre that a lot of people feel (even those who make it and listen to it) uncomfortable with for that very reason. In this section are three (or four-ish) pieces. The first is a two-part piece about Sufjan Stevens, with each part written ten years apart. Stevens has been an important figure in the “Christian music” world despite clearly never intending to be a part of it, and is the only musician featured in this section who is not also an ordained clergyperson of some stripe. The next is about the band Luxury, who may have inadvertently stumbled into Christian rock in the 1990s but took a sharp turn away from it soon thereafter, even though they continue making deeply spiritual rock and roll. (I once tried to write an article about them called “Luxury: The Only Christian Band,” which I could not finish, but which, I think you’ll agree, is apt, given how many members of the band are ordained priests.) This section ends with an interview I did with a man improbably named Slim Moon, who runs one of the most respected independent record labels of all time, Kill Rock Stars, and who, also improbably, is also an ordained Unitarian minister.

![]()

All Things Go: How Sufjan Stevens Changed What It Means to Make Christian Music

If someone asked, I would say that I was born again. I would look you right in the eye and say it.

—Sufjan Stevens, in a 2005 interview with Plan B magazine

2005 was very much the year of Sufjan Stevens in the world of American popular music. His fifth album, Illinois (or Sufjan Stevens Invites You To: Come On Feel the ILLINOISE) was, according to the website Metacritic, the most favorably reviewed album released all year. He sold out five consecutive nights at the Bowery Ballroom in New York City, and played Carnegie Hall. Stevens’s music could be read about in all the major music magazines, was hard for independent record stores to keep in stock, and could always be found on evangelical pastors’ iPods. Yes: Sufjan Stevens is not just the most lauded musician of 2005, but also a real-life Christian, and a high-church one at that (in an interview, he described his Episcopal congregation as “Anglo-Catholic”). And it is his music, in part, that perhaps permanently changed the idea of what “Christian music” can be. (Pop culture critic Jeffrey Overstreet declared, of Stevens’s music: “The wall is down. There is no more reason for the Christian music industry to exist.”) How could this thirty-year-old short story writer from Michigan, with a slight lisp and a Muslim name (which his parents chose after a brief association with the new religious movement Subud), who plucks a banjo plaintively and whose voice is rarely raised above the volume that might be reserved for a serious discussion about anthropology, become the savior of “Christian music”?

There are reasons for Stevens’s (deserved) mantle of leadership in this new Christian music movement, perhaps the most important being that this is not a movement, nor is it, strictly speaking, Christian music. You see, for about thirty-five years, something has existed called Contemporary Christian Music (CCM), something initially conceived by hippie rockers who wanted to sing about Jesus that eventually became a multimillion-dollar industry based on record companies and marketing firms who were experts at selling a particular idea about music to evangelical Christians. That idea was: here is some pop music that sounds a lot like what you might hear on any radio station, or on MTV, or your friends’ record collections, but instead of being about romantic love or having a good time, is about God, and is devoid of swear words, drug references, and sex.

CCM was and is many things—a “safe” alternative to morally debauched rock or rap, a way to praise the Lord to a funky beat, well-crafted songs about love and spiritual longing made by evangelicals who want to make songs for Christians—but it has almost always, since its inception, existed in a cultural silo. CCM, though it has no flagship style, is considered a genre from a marketing perspective, complete with a readymade target market—“people of faith.” From time to time, CCM has produced “crossover” artists who eventually sign with major labels who market their music in places other than Christian bookstores to varying degrees of success, including Amy Grant and Michael W. Smith in the late 1980s, Jars of Clay and Sixpence None the Richer in the mid-1990s, and Switchfoot and Underoath in the early 2000s. Most “crossover” artists attained a significant degree of success in the Christian market before making the leap, and each has faced unique challenges from their evangelical fan base (“they’ve abandoned their faith!”) and “secular” pop fans and critics (“Christians playing rock music? Please!”). Significantly, almost all of these crossover artists are affiliated with what are called “major labels,” large corporations that are more in the business of shifting units and pleasing shareholders than delivering artistically relevant music.

But Sufjan Stevens did not cross over; he didn’t have to. From his 2003 album Michigan, Stevens captured the ears of serious music listeners, Christian or not, and did so without participating in any of the practices that create the possibility of crossover. Stevens has never been signed to a Christian record label; his records are all released on an independent label, Asthmatic Kitty Records, which he co-founded. His music has not been sold in Christian bookstores, advertised in Christian publications, or played at Christian festivals. Stevens’s lyrics are not Jesus smackdowns, they’re beautiful portraits of humanity: hope, love, joy, peace, pain, murder, sickness, alien invasions, unemployment, history, road trips, faith. “Casimir Pulaski Day” from Illinois is a tender story of young lovers whose relationship is cut short by parental disapproval and cancer. The song is bathed in prayer and hope, but ends with death and resigned thankfulness, as Stevens praises God even though “He takes / and He takes / and He takes.” The chilling and ethereal “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.” is a heartbreaking ballad about the sadistic serial killer that ends with Stevens alone, in a wavering tenor, claiming “in my best behavior / I am really just like him.” The song is terrifying in its depravity and beauty, and nakedly blunt and personal in its assertion of the doctrine of original sin.

It’s not just that Stevens is a critical success, as if that somehow proves that “the world” can learn to respect music about God as long as it’s as cool as “secular” music; it’s that he has made music with integrity from the beginning, never adding or subtracting the word “Jesus” from a song to appease someone, never hawking minivans or snowboards with his music, never bending a vision of God-glorifying art to be less “worldly” for the Christian market or less Jesusy for the secular rock market. Sufjan Stevens has proven that CCM is over (if we want it); as he and his chorus sing on “Chicago”: “All things go.” Stevens’s artistic success is proof that people who seek God don’t have to settle for ghettoized, bowdlerized pop music. This non-movement is ever on the move, and people who care about both ...