![]()

PART I

![]()

CHAPTER 1

IN THE STREETS OF THE CITIES

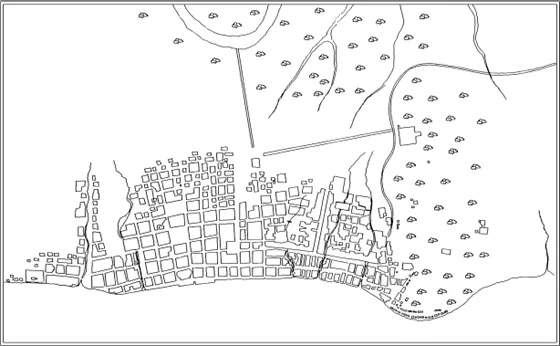

Map of Guayaquil. Based on a map published by Manuel Villavicencio in Geografía de la Reública del Ecuador (1858) with correctives made for the late date.

In the 1820s María Magdalena and her daughter Ana Yagual found themselves living in Guayaquil at a tense but optimistic moment. Times were changing rapidly, and many residents believed their city would be able to benefit. British merchants who visited the city during the independence period and explored the possibilities were full of enthusiasm. Consul Henry Wood reported to George Canning:

As a commercial station there are few ports which possess such vast natural advantages as Guayaquil. [It is] situated on the bank of a magnificent river of the most easy and secure navigation, surrounded by a country capable of producing an immense quantity of exportable produce, and intersected by numerous minor rivers which serve to facilitate its transportation … Guayaquil further offers every facility for the repairing and building of ships. Although there are no docks, ships of very considerable burthen may with security be “hove down” at the river’s side and thoroughly repaired. The timber used at Guayaquil for the purposes of ship building is in point of durability perhaps superior to any in the world.1

María Magdalena and Ana Yagual had to wend their way through the market’s profusion of trade goods. Newcomers were usually overwhelmed. “Everything is recommended to you, and your ears are saluted with the cry of ‘Barrato, muy barrato [cheap, very cheap],’ at every step.”2 The local ships from Guayaquil and from Chile and Peru and elsewhere along the coast came and went with butter, lard, soap, sleeping mats, mattresses, quilts, carved boxes, fruit, wine, flour, tanned goatskins, sea lion pelts, tobacco, cigars, raw fibers, cordage, cotton, and straw hats.3 The smelliest crates contained oil: the best was from the sperm whale, but the oil of the giant Galápagos tortoises that once swarmed the islands named for them was cheaper. Other goods came from the hinterland for the cityfolk to eat: rice, beef, pork, poultry, and fish from upriver. Most plentiful of all were the fruits and vegetables brought by Indians on rafts, especially the bunches of plantains, the staple of all the townfolk, rich and poor. Bright Andean textiles and animal skins came in on smaller river boats and mule trains from the mountains. In exchange for these, Guayaquil’s merchants sent back to the highlands local products and luxurious European goods: wax, crystal, china, paper, razors, knives, silk stockings and breeches, cashmeres, satins, fine cottons, ink, wine and other liquors. They also received the more mundane bars of iron, tea, boots and shoes, and a few manufactured shirts and pants.4 The foreign ships always left again with cacao beans, used to make cocoa powder for the popular beverage. Sometimes they also left with specie in gold or silver, or with lumber or unprocessed cotton or other raw materials, but they always took some cacao.

Everyone in the city knew that cacao was Guayaquil’s trump card. The racks of the drying beans were among the most common sights in town. The fruit, which grew on trees and was as big as a melon and bright pink when ripe, came from plantations for miles around. No one left the precious fruit out to spoil in the heat. People cracked it open and dug out the brown beans (each one as big as a cat’s foot) and left them to dry in the sun. The smell was delicious, reminding some passersby that there were fortunes to be made here. The energy that the import-export trade brought to the port reverberated in all the streets of the city, past the port and the markets in four directions, extending down long streets and up neighboring hills. The focus, however, remained the river that brought the ships.

The city really began in the river, in a floating neighborhood borne on rafts. If the newly arrived María Magdalena and Ana Yagual knew someone who lived in the aquatic barrio, they might well have gone there first. Despite all the efforts of the authorities to reduce the size of this warren, the river-borne village had existed for years. Some people built little houses on their rafts, and others operated taverns. Some guided their crafts away from the city in times of war troubles. The raft dwellers said proudly that at least they never had the problem of the foundations of their dwellings rotting away in the rainy season. During the day, the river dwellers were joined by other city folk, who came to wash clothes or to bathe. They shared an exhilarating fear of the alligators that sometimes prowled the area, and occasionally they enlivened the day by trying to catch one alive and then taunt and kill it.5

This riverbank was the gateway to the world; here faraway places did not seem so far away. The water was deep, and big ships could approach the city fully loaded: there were fifteen to twenty in the port on an ordinary day. People stepping off them had been in Lima or Callao in Peru only a week ago, or two weeks ago in Panama, where they had seen the Caribbean Sea. Sometimes they came from much further, from the United States or England, and the big, sunburnt men aboard shouted words in English that made the children laugh. As soon as the first load of passengers or cargo was put in a balsa and sent ashore, excitement broke forth in the port. Arrivals averaged one every other day, and each new arrival brought news and work. Indians who lived on the anchored balsas or who came from just outside the city rushed toward the ship with their small boats. The docks were not well developed: no one had bothered to invest much money in them because there was no need. The indígenas were always there to cart goods in their boats and on their backs for little money. Since long before the arrival of the Spaniards they had been navigating expertly with a twist of a sail or a rudder in their balsas made of tree trunks, bark, or sea lion skins. Individuals could maneuver on a single trunk, “maintaining so exact a balance, that although the log is round they very seldom fall off.”6

Near this neighborhood of boats, the shipyard came into view. Here the men working on the boats were not Indians. They were black. So were some of the men shouting orders. These were the children or grandchildren of Africans, some of whom also had Indian and white forebears. They worked amidst piles of timber brought from nearby parts. The tools and other materials they used were familiar to any observant foreigner, for they were nearly all imported from Europe. People here spoke with pride about the fine quality of their timber and craftsmanship. They pointed to one boat and claimed it had lasted almost one hundred years. In 1828 the men here converted the sailboat Felicia into a steamer, albeit a fragile one.7

The malecón, the wide street that ran along the river, charmed newcomers when they first saw it. It was paved with rock and crushed oyster shells. The stonework edging the water was quite new. Construction had begun at the end of the colonial era and would continue intermittently until the local government began to push in the early 1830s to finish the job. The city officials even started a lottery to raise money for the work. Tickets cost four reales, at least a day’s wage for a laboring man. A “child of the multitude” was randomly chosen to draw the numbered balls from the bin.8 The roadway was lined with 102 crystal lamps, lit nightly by city workers. The stately wooden houses were impressive. All of them were white, with tiled roofs and balconies extending the width of the building or recessed ground floors. They were built close together, so that someone walking below was always protected from the sun or the rain. Here lived eminent citizens. Gauzy curtains fluttered from the upstairs windows, and sometimes fine ladies stepped outside, talking and laughing. Many of the lower floors housed elegant shops or inviting cafes. Someone with money could stop to rest and order sweet bread and a glass of fresh fruit mixed with the crushed ice that was transported down from the mountains.9

This part of the city, called the Ciudad Nueva, was the most modern, cosmopolitan neighborhood. One block in from the malecón, and parallel to it, ran the Calle Comercial. Here were many shops, from ordinary textile sellers to fine chocolate makers and watch repairers. The streets which led inland, perpendicular to the main thoroughfares, bore the names of well-known landmarks: Street of the Church of San Francisco, Street of the Theater, Street of the Prison, Street of the Shipyards … Between the malecón and the Calle Comercial loomed the large, modern Casa Consistorial or government office building, the first floor of which was lined with small shops. At the corner there were weekly newspapers for sale, although few people bought them, as they were expensive and most people could not read them anyway. Interspersed along the inner streets were well-known artisans’ shops, including an especially large shoemaking establishment, bakery, master blacksmith, and several rum distilleries.

In giving directions, however, people did not usually locate themselves in relation to such edifices and only rarely used the names of the streets. They said instead, “Across from the house of las Señoras Rocafuertes …” They knew where the principal houses were, interspersed throughout the city, for no neighborhood was entirely reserved for the wealthy.10 Different social classes often shared the same building, as the lower floor frequently housed servants or was rented to the family of an artisan or shopkeeper. The Elizalde family was one of the most elite in Guayaquil, and even Juan Bautista Elizalde rented his ground floor to a tailor (albeit a French one) and then to the owner of a cafe who advertised in the newspaper. Other houses had floors divided into cuartos or apartments rented to families. In such cases, there might be more than one kitchen built in the rear or in the courtyard. Everyone in the Ciudad Nueva, rich and poor, shared these conditions. Each morning they shooed the same wandering pigs and dogs. They all heard peddlers crying their wares, water carriers selling their precious commodity, and passing herds of goats bleating. Church bells rang, and somewhere on the street a musician played.

Whatever the pleasures of life in Ciudad Nueva, however, Ana Yagual and María Magdalena found no shelter there. They continued on to the poorer part of town. To get to the Ciudad Vieja they had to cross a bridge over a small estuary leading into the river. Past the bakery near the bridge, at the base of Santa Ana Hill, two ferocious-looking cannons were trained on the river. Looking up over the warren of houses, they could see the Iglesia Santo Domingo, built of heavy stone. Everybody knew it was the oldest church in the city, the first the Spanish had built. For in the beginning everyone had lived here on this hill, using the cannons to defend themselves against angry Indians or pirates. Then the city began to grow lengthwise, hugging the riverbank. When the city was about a hundred years old, the wealthy began to invest in the shipyards, building them away from the crowded hill where the people lived. Tiny rivulets cut into the land perpendicular to the river, creating a series of small peninsulas that made it difficult to walk to work. So the owners of the shipyards built bridges over the rivulets; suddenly it became possible for the city to become much bigger. Those who had the resources moved off the hill and across the bridges, until eventually there were only poor families left there. The Dominicans from the church had complained as early as 1768 that they were hardly able to collect rent anymore from the houses built on their property. There were only “poor black people” remaining. On the stiflingly populated Santa Ana Hill, smoke from the cooking fires hovered in the houses, filth ran down the narrow alleys and stone steps, and disease spread rapidly.11

Ana Yagual and her mother crossed the hill and headed for the plain that wrapped around the town on both sides, the “savanna” as it was called. Between May and December it was hot and dry, but pleasant and cool when the sun went down. Between January and April it was steamy hot, and either was raining or had just rained. Then the streets beyond the paved ones close to the malecón ran with mud and made it useless for anyone to attempt to use a carriage or a cart. There was a decent road to the cemetery on the edge of town, but if people’s way lay toward the slaughterhouse or the tannery instead, then they had a difficult walk. Recently, more people had been building bamboo houses here. To cope with the rainy seasons, they built them on stilts, as the indigenous peoples of the coast had long been accustomed to doing. In the sheltered areas beneath they cooked and kept their animals. When they were ready to go inside, they climbed up a ladder. Those who were better off partitioned their one room into two; usually the only furniture consisted of a hammock.12

Here the people shared many of the problems of the inhabitants of the Ciudad Vieja.13 Water had to be carried for a long distance or up a steep incline or bought at high prices from the aguateros. The entire city swarmed with mosquitoes, but the people in this part of town could not afford mosquito netting. It was difficult to keep the dirt floors free of snakes, scorpions, and the dangerous niguas, insects which laid their eggs in bare feet. When an army of ants carried off the bread, it was often impossible to find the money to buy more. Sometimes fifteen people lived in one room; even with so many contributing, it usually required all their resources to survive from day to day. There was rarely anything left over. The cost of living had doubled in the last thirty years. An influx of people into the city had brought wages down. Less food was available, as war had interrupted production and more landowners were growing the valuable cacao instead of food crops. More people and less food meant higher prices: one chicken could cost as much as three reales, and an ordinary jornalero or day worker earned only three or four in a day. Renting a room cost at least three pesos (or twenty-four reales) a month. To raise revenue, the government had imposed monopolies on tobacco, salt, and even flour, which rendered bread more expensive. There seemed to be taxes on everything, including marriage. Priests were only supposed to charge three or four pesos for a ceremony, but they often charged thirteen or fourteen instead.14

Who were these people crowding onto Santa Ana Hill and building mor...