![]()

One

Tractatus Esthetico-Semioticus:

Model of the Systems of Human Communication

Charles Seeger

What one cannot speak of may long have been drawn, carved, sung, or danced.

This essay outlines a general theory in accord with which the communicatory systems—that is, the arts and crafts—of man and their cultivation in their common physical and cultural context may be presented with least distortion by the inescapable bias of the system in which the presentation is made—the art of speech. Both theory and model are speech constructs. But, except for speech, the arts and crafts and their compositional processes are not speech constructs. Their names are; but, except for speech, they do not name themselves. Speech names them; that is, we name them by means of speech, for that is the only way in which we can name, relate names in sentences, relate the named among themselves by means of more names, and relate the relations among the names to the relations among the named.

As is speech itself, all systems of communication known to us, both nonhuman and human, are known directly to us as are we ourselves to ourselves. To the extent we hold, in speech presentation, that this knowledge is real, to that extent we can say that we are real and that they, their compositional processes, and what these communicate are real. We have the “working” metaphysics of “common sense”—an epistemology; an ontology, a cosmology, and an ethology, or ethics (axiology, theory of value)—for we imply that it is worthwhile saying so. The more adept we are in the compositional process of speech, the more elaborate and extended the reality.

But speech is a many-edged tool. We do not know, cannot say, or find not worth saying at least as much as we do know, can say, or find worthwhile saying. Of whatever we say, we can say the opposite. Or we can qualify it. And we can find that much of such saying may seem equally worthwhile. Thus, we have developed an indeterminate number of ways of saying things and of realities. The tendency has been for each user to propose or take for granted that one way of speaking is better than another and that his reality is the reality.

To avoid such simplism, we may distinguish three principal modes of speech usage. All the above ways of speaking are variants, or hybrids, of these modes. The first, general, discoursive, is the mode of “common sense” and its more sophisticated versions, sometimes referred to as “uncommon sense.” The second and third are specialized—one is belletristic, poetic, mystical, and the other, logical, mathematical, scientific.

Each specialized mode can be said to produce its own characteristic reality. Treatment of reality in the discoursive mode varies between the extremes of adherence to a particular reality of a specialized mode and either the skeptic’s denial of reality as factual and valuable, or verbal protestation of one reality with behavior that is in accord with another.

The boundaries of the modes vary. Those of the discoursive shade off gradually into the domains of the specialized. The boundary between the logical and mystical modes is fairly sharp as far as individual users of them are aware, but below the threshold of awareness the boundary is very easily crossed.

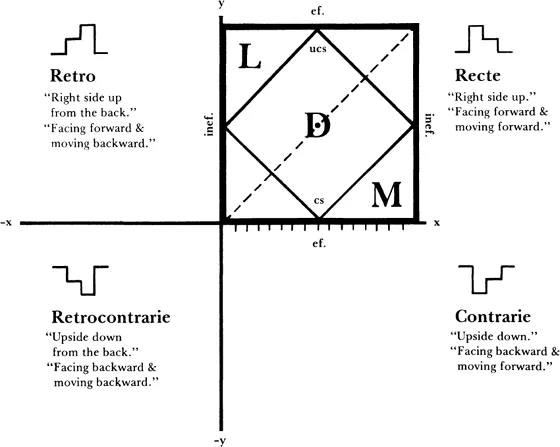

The relative coverage of the total potentiality of speech by the three modes is probably still far from complete. Since there is no conceivable unit of measurement, their relative coverage may be considered equal, as visually represented in figure 1, with each mode covering half the total area. The following steps explain figure 1:

1. The heavy-lined square xy is a skeletal model (visual) of the total communicatory potential of the speech compositional process viewed as the maximal unit of form of that process.

Figure 1. Two-dimensional visual projection of the coverage of the total communicatory potentiality of speech by the three principal modes of usage, in its four simple transformations that are possible in the compositional processes of all principal systems of communication among men. See text for explanation of symbols.

1.1. The heavy-lined capitals, D, L, and M indicate the relative potential coverage by the discoursive, logical, and mystical modes of speech usage viewed as at least potentially universal.

1.2. The dotted line separates the potential coverage of the total by the L and M modes; the light-lined square separates the potential (overlapping) coverage by the D mode.

1.3. Inner elaboration and (outer) extension of coverage is calibrated: (a) in the L mode on the top line of the heavy-lined square in accord with fields of interest (from left to right, logic, mathematics, natural sciences, social sciences, communicatory theory, esthetics, empirical philosophies); (b) in the M mode, roughly, on the bottom line, in terms of literary genre, style, or whatever (from left to right, scientistic-critical speculation, idealist philosophies, scientistic and impressionistic criticisms, belle-lettres, poetics, mythologies, religious, mystical, and ecstatic speech); (c) in the D mode, by general common sense (CS) through a vaguely definable hierarchy of increasing competence to the “uncommon common sense” of disciplined judgment (UCS).

1.4. The limits of inner elaboration and (outer) extension are indicated: (a) for the L and M modes by the left and right sides, respectively, of the large square; (b) for the D mode by the central dot (·). For time present—and possibly, if not probably, past and future—the realities of the L and M modes may be taken as ineffable (inef.); the reality of the D mode, as variably both effable (ef.) and ineffable, depending upon focus of attention and distance from the central dot. Often as not, opposite realities are professed and acted upon by one and the same person.

2. The stenogram at the right of the large square stands entirely arbitrarily for the unit of esthetic-semiotic form of each of the several systems of communication among men—tactile, visual, and auditory, including speech. Thus, a fourfold transformation of the unit can be modeled upon the axes of two-dimensional coordinates uniformly for all systems.

2.1. The positive axes upon which the large square is projected are extended to indicate three other projections: two, half-positive, half-negative; one, wholly negative. The compositional processes of all systems except speech employ all four of these projections, or transformations, as integral elements of both their esthetics and their semiotics. In the speech-compositional process, the transformations lie at the base of the elaborate and extended panorama of conceptualization found in nearly all languages. Thus, for an elementary example, we could represent concepts of antimatter, antitime, and, for all I know, anti-space-time, as x −y, y −x and −x −y, respectively; but, except for amusement, we do not spend much time using palindromes (x −y), and it is impossible to pronounce words upside down or backwards and upside down. The absurdity of the attempt can be shown by such simple verbal transformations as are found in transformational linguistic trees:

Doctor gave Bill a pill

Bill gave Doctor a pill

Pill gave Doctor a Bill

Pill Bill Doctor gave a, etc.

The esthetics are fully transformable, 120 in all, but the semiotics of 118 are nonsense. If given four esthetic units of form as commonly met with in the compositional process of any other art or craft, it is not difficult to find analogous transformations that are traditional components of their compositional processes, few or none of them semiotic nonsense.

2.2. In the present model, the names of the four tranfsformations are borrowed from musicology (Recte, Contrarie, etc.); the words below them are borrowed from visual and tactile systems.

3. The square is, therefore, the exclusive speech variant of the stenogram; but it is in its terms that we may try to speak of any or all the others. Therefore, the undertaking to align the compositional process of speech with that of any other system is subject to severe strain simply upon technical grounds, in that speech is the only one of the lot that is ineluctably symbolic at its base: its esthetics symbolize, represent, its semiotics. The rest present theirs. We are in a position precisely the opposite of Lord Rayleigh when the lady told him she had enjoyed his lecture on electricity but that he had not told her what electricity was. Lord R., sotto voce: “I wish I knew.” By virtue of our being adept in the compositional process of the system being talked about, we know but we cannot say.

The provenience of these three modes and their realities is uncertain—a matter for speculation in prehistory. A highly developed discoursive mode was, however, existent in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, and their contemporaries. The farthest reaches of both specialized realities were open to discourse in their “uncommon sense” and led to proposals for resolution of many of the incompatibilities and contradictions among the lot. But, long before the present writing, the logical and mystical modes became set up separately as mutually exclusive opposites. Most users of each still try to keep them so. And successfully, in that the writings of both are often incomprehensible to each other and to nonspecialists. But, in spite of their contradictoriness, they are ineluctably interdependent and complementary: the logical, on the one hand, depends upon the mystical for an unspoken assumption that the unlimited pursuit of knowledge of fact is worthwhile—that is, valuable—for which there is no logical or scientific evidence whatever and which is inconsistent with all the other carefully reasoned assumptions of the mode; on the other hand, the mystical mode depends upon the logical for the apparatus of the lexicon, the grammar, and the syntax required for reference to the highest values, as, for example, the name “Tao” in the first line of the Tao Tê Ching (a prime example of the mystical mode) is not the name of the Tao. The result—the great philosophical joke of all time—is the twentieth-century discovery, through the principles of complementarity, indeterminism, and uncertainty (not to speak of Planck’s constant, of which I have minimal, perhaps no, understanding), that the ultimate reality of the physical universe is still just as ineffable as the ultimate realities of the Vedas, the sayings of Buddha, and the Tao Tê Ching. The one says, “Although hopeless, it is worth trying”; the other, “Because it’s hopeless, there’s no use trying.” Both, I believe, are in error: the logical, on account of the uncriticized assumption of worthwhileness, which may be leading to serious damage of the biosphere; the mystical, because of its indoctrination of enormous populations with verbal mystification with the result that, until modern times, the class of adepts in speech was kept in positions of undisputed economic, political, and social power.

The present undertaking is written in the discoursive mode of speech usage. The core of this mode is the critique. It is the particular job of the critique to try to resolve the contradictions of the two specialized modes, to show their complementarity, and to construct a unitary speech concept of reality that takes into account the realities of the full roster of communicatory systems other than speech.

I owe the title, the idea for the epigraph at the head, and something of the outer form of the essay to my contemporary Ludwig Wittgenstein. Until about 1960, when work on this essay began, I had put him down as but one more logical positivist. I knew him only through his Trac tatus Logico-Philosophicus, which, in spite of the admirable austerity of its literary style, showed only too plainly that he was imprisoned in the linguistic solipsism of traditional philosophy—the attempt to view speech solely from the inside, as it were, from the viewpoint of the adept in speech alone, to make it hoist itself by its own boot straps—although he came closer to escaping from this linguocentric predicament than any other writer known to me. Had he been as adept in another system of communication as in speech, he might very well have cast the turnabout that he made in his Philosophical Investigations under just such a title as mine and achieved an approximation of the objectivity toward speech as a tool that he sought but thought possible only in a perfect language, which he admitted must be an impossibility.

The moot question is: But, supposing that we might look at speech objectively from the viewpoint of another system of communication, how could it be expressed except in speech?

Admittedly, the case itself is a speech construct. It has not been distinguished nor is it conceivably distinguishable in terms of the compositional process of any other system. The very conception “viewpoint of another system” is itself a speech construct. The question becomes, then, two-pronged: first, To what extent can the compositional processes of two systems, one of them speech, be operated simultaneously by one person adept in both and be reported upon in speech? and, second, To what extent may the two compositional processes operate independently or interdependently not only above but also below the threshold of our awareness?

Talking about what one is doing or about something entirely unrelated to it while making music, painting a picture, dancing, making love, fighting, whittling, or working on a conveyor belt is common practice. Keeping in mind the knowledge of what one was doing in such activities is quite another matter. To the extent, however, that we believe and give evidence that we can do this, we may then review in terms of speech what is said by ourselves or by others about it. To the extent that we can generalize such review, we can begin to lay the base of a critique of the speech compositional process with reference to the compositional process of another system. Such a critique of speech is not to be confused wit...