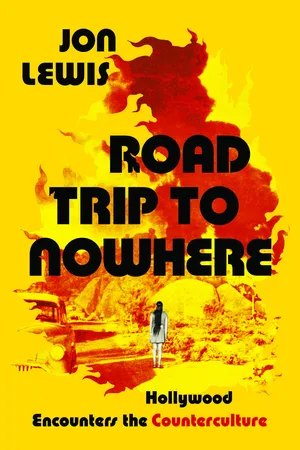

![]()

1 Road Trips to a New Hollywood

Easy Rider and Zabriskie Point

A perplexing crossroads dilemma for a movie industry on the brink: What can be done to get young Americans back into the habit of going to the movies? The answer as the sixties wound to a close seemed at once apparent and impossible, weirdly tied to two very different movies grounded in two very different traditions: the European New Wave and B-Hollywood. The collective fortunes of studio Hollywood thus fell to two very different men: Michelangelo Antonioni—an Italian cineaste whose career had suddenly changed course thanks to an unlikely global box office hit, the swinging London thriller, Blow-Up (1966)—and Dennis Hopper, a veteran B-actor and counterculture scene-maker whose low-budget biker road picture Easy Rider (1969) became for Hollywood the most talked-about movie in a decade.

Both Blow-Up and Easy Rider made a lot of money for their American distributors off small investments—and, indicatively, off virtually no studio involvement in their production. Neither set a course the studios could so easily or reasonably follow. Executives at the studios nonetheless tried. And in trying, they encountered a new breed of Hollywood talent: movie stars who didn’t want to be movie stars and movie directors who frankly wanted nothing to do with the studio business model and hierarchy.

Antonioni followed up Blow-Up with Zabriskie Point, a film MGM paid him to make and then abandoned when it was done. The film’s handsome young stars were well out of the business within a year or so of the film’s release. And when Antonioni declined to make another Hollywood film, no one tried to change his mind.

After Easy Rider, Hopper was quite astonishingly the hottest director in Hollywood. So he decamped to Taos, New Mexico, to tap into vibes from the Native American community that once lived there. He took up artistic residence near the onetime residences of two legendary artists: the writer D. H. Lawrence and the painter Georgia O’Keefe. And then banked his filmmaking future on a ramshackle western made on location in Peru: The Last Movie. The title all too aptly spoke to his future in Hollywood.

Blow-Up: Michelangelo Antonioni’s Mod Masterpiece

Intoxicated on prerelease buzz about their hip new thriller, Blow-Up, executives at MGM planned a holiday-season 1966 North American release. The film premiered in New York just before the New Year, in time to qualify for the Oscars. The reviews were terrific—offering promise (which would be fulfilled) for a wider spring 1967 release.

The spring playoff was buoyed by a nice surprise from the Motion Picture Academy as Antonioni got an Oscar nomination for Best Director. The nomination was unusual for such a fully international production: directed and produced by Italian filmmakers (Antonioni and his producer Carlo Ponti); based on a novel written by Julio Cortazar, an Argentine; shot on location in London for a British production company (Bridge Films); with a cast comprised of a who’s who of the swinging London scene—actors David Hemmings and Vanessa Redgrave, model and actress Jane Birkin, rhythm and blues band the Yardbirds (for-real rock stars who perform live and don’t disappoint: guitarist Jeff Beck’s amp short-circuits and he quite wonderfully smashes his instrument on-screen), and the German-born supermodel Veruschka. The casting proved canny, the setting well chosen, the vibe spot on.

Even better news followed in May as Antonioni and the film won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. The US theatrical run was by then in full flight and it well exceeded expectations: $20 million domestic off MGM’s investment of less than one-tenth that amount. Things were all good with the unlikely arrangement—MGM and Antonioni, that is—until they were bad, really bad. But that was still a few years away.

Blow-Up was unlike anything MGM had in release or development in 1966. Their release slate for that year was headlined by The Singing Nun (Henry Koster), a Debbie Reynolds vehicle that’s about, well, singing nuns, and the Doris Day spy spoof The Glass Bottom Boat (directed by the Looney Tunes/Jerry Lewis vet Frank Tashlin)—two films that exemplified the studio’s endemic generation gap. The studio’s top grosser for 1966 would be John Frankenheimer’s nearly three-hour motor racing melodrama Grand Prix—a bloated epic that cost so much to produce it failed to meet the industry’s measure for break-even at the box office.

When MGM signed Antonioni to a three-picture contract in 1966, it sent a clear message—a first affirmative move to cash in on a transitioning marketplace, a marketplace driven by the young in fact and at heart. It took into account the astonishing popularity with young filmgoers of the European art picture in general and with Antonioni in particular.

Blow-Up seemed to MGM execs the perfect film—and the negative pickup deal the perfect hedge—to trial run a relationship between Hollywood and the European New Wave.1 In an industry that favors “ideas you can hold in your hand” (an adage frequently credited to Steven Spielberg, but it had been in play since the twenties), Blow-Up also and uniquely fit that bill as well: quite by accident a fashion photographer captures on a roll of film what looks like a murder, and those implicated in that crime endeavor to silence him. Blow-Up was a foreign art film the executives actually understand and like.

FIGURE 6. Quite by accident a fashion photographer (played by David Hemmings) captures on a roll of film what looks like a murder in Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966, Premier Films/MGM).

After the Oscar nominations and the Palme d’Or, and after pocketing the box office revenues, the American executives seemed (finally and for a change) smart. The critics (finally and for a change) were on board too. Andrew Sarris dubbed Antonioni’s film, “a mod masterpiece.”2 And Bosley Crowther, the curmudgeonly New York Times critic, gave the film a good review, offering a terse characterization of the film that neatly doubled as an elevator pitch: “[Blow-Up! is] vintage Antonioni fortified with a Hitchcock twist.”3 Marketing executives at MGM could not have put it better.

Learning to Love the Foreign Art Film

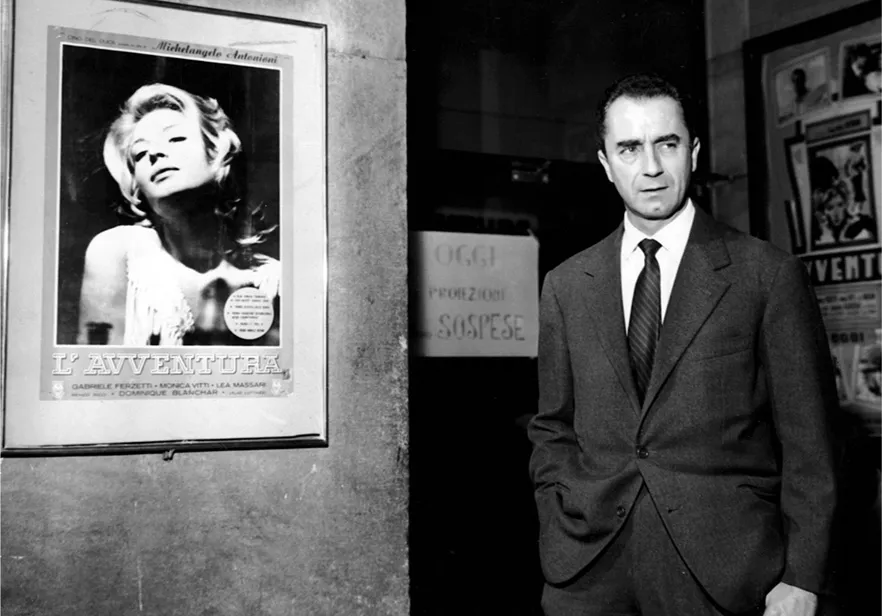

Antonioni first became an important figure on the international scene in 1960 when his film L’Avventura was showcased at Cannes. L’Avventura was met with open derision by audiences and then won the Jury Prize despite, or (it’s Cannes, after all) because of the film’s frustrated reception. The film then reached American screens in the spring of 1961 along with an even more impactful Italian import, Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, which grossed nearly $20 million in the United States—an astonishing figure at the time. An American film culture assembled around these two European art films, and much to the studios’ collective envy, a niche market emerged for a new wave of foreign films.4

The critical response to L’Avventura in the United States was rapturous—a harbinger of things to come. Sarris dubbed L’Avventura “a sensation.”5 Stanley Kaufman in the New Republic described its influence on film language and history as revolutionary: “Antonioni is trying to exploit the unique powers of film as distinct from the theater. . . . He attempts to get from film the same utility of the medium itself as a novelist whose point is not story but mood and character and for whom the texture of the prose works as much as what he says in the prose.”6 When a panel of international reviewers was asked by the British film journal Sight and Sound in 1962 to assemble a list of the Top Ten Best Films of all time, it ranked L’Avventura at number two, behind Citizen Kane.7

Antonioni’s subsequent films—La Notte (1961), L’Eclisse (1962), and Red Desert (1964)—offered a steady diet of rich, handsome, and disaffected characters traipsing around a deceptively scenic postwar Europe. The three films are so consistent in their stories, themes, and mise-en-scène that when the director made the move to color in Red Desert it was for critics and serious filmgoers a contentious topic, like Dylan going electric. After four such metaphysical melodramas, Blow-Up seemed for the director a sudden change of course, a point of departure. At least that was the view executives at MGM were anxious to take.

FIGURE 7. Michelangelo Antonioni beside a poster for the film that launched his career, L’Avventura (1960) (Everett Collection).

Just after Blow-Up completed its run, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) president Jack Valenti took to the pages of the trade journal Variety to voice concern about the newly inflated value of foreign-made pictures in the American film marketplace. He reproached American film reviewers for failing to support the Hollywood product, for becoming “hung up on foreign film directors whose names end with ‘o’ or ‘i.’ ”8 First and foremost on Valenti’s mind were Antonioni and Ponti, the brains and the money behind Blow-Up. Well repressed, of course, was the essential irony that Valenti’s last name also ended in i.

Anticipating an obvious question—precisely who stateside in 1966 was prepared to make movies that could capture the interest of the many American moviegoers and reviewers who patronized the European art film—Valenti offered an answer, boldly announcing: “The future of the film business lies on the [college] campus.”9 The prediction proved accurate, as a new generation of film-school-educated auteurs, later dubbed “the movie brats,” arrived on the scene. But in an irony likely lost on the MPAA president, these young auteurs—Francis Coppola and Martin Scorsese, to name just the two most prominent—were themselves rather enamored with and influenced by the films of foreign directors whose names ended in o or i.

Blowing Up the Production Code

To start: dealing with Antonioni was never going to be easy for MGM. He had by 1966 earned a reputation as an uncompromising and pretentious artist, as a singularly independent filmmaker with idiosyncratic methods. After every setup and before every shot, he liked to sit at the camera, thinking, as the cast and crew waited. MGM hadn’t had a good year in some time, so we can understand why they were willing to deal with almost anything, almost anyone if they could get back on track. They really wanted Blow-Up; they really needed Blow-Up. So they entered into to a contract with Antonioni—a contract that explicitly gave the cineaste control over the final cut.

The issue of final cut was from the outset consequential. MGM executives had seen Blow-Up. So they knew about the scene at the photographer’s studio—a scene that featured full-frontal female nudity. The MGM contract with Antonioni was meant to be the beginning of something. And as things played out, it was the beginning of a lot of things and not just for MGM. A simple rule of thumb: In the movie business, when they say it’s not about the money, it’s about the money. And when they say it’s about public morality, then it’s absolutely about the money.

Blow-Up was never going to get a production seal from the MPAA and the executives at MGM knew that going in.10 And yet they signed the contract anyway.

When MGM released Blow-Up without a production seal, they did so appreciating the message they were sending to the other studios—the agreements, policies, and procedures they were defying. A basic and widely shared understanding had prevailed in Hollywood for over three decades: that no one film is bigger than the industry, that sacrificing free expression (for example, cutting an offending scene or line of dialogue) to suit the censors was a fair price to pay to maintain the necessary fiction of social responsibility, to maintain a predictable and amicable marketplace.11

MGM tried to be cagey about defying the MPAA. When they distributed Blow-Up, the studio’s name and logo were conspicuously absent. The film reached theaters under the Premier Films banner, technically a Bridge Films/Carlo Ponti British-Italian coproduction released by an American “independent” distribution company, a company that MGM had in fact created solely to release the film. It was a convenient fiction. And it fooled no one who mattered in the business.

Executives at MGM knew that the Premier Films release was a calculated gamble. It was hard to predict how the management at the other studios might react or how, as a consequence of their decision to subvert MPAA authority, the censors might in the future judge other MGM films. It was also a gamble concerning the nation’s exhibitors: would they be willing to present a noncompliant film to their local clientele? Turns out, theater owners were...