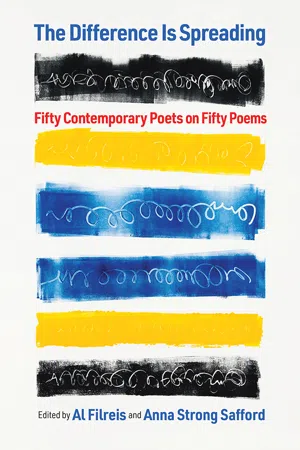

The Difference Is Spreading

Fifty Contemporary Poets on Fifty Poems

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About This Book

Since its inception in 2012, the hugely successful online introduction to modern poetry known as ModPo has engaged some 415, 000 readers, listeners, teachers, and poets with its focus on a modern and contemporary American tradition that runs from Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson up to some of today's freshest and most experimental written and spoken verse. In The Difference Is Spreading, ModPo's Al Filreis and Anna Strong Safford have handed the microphone over to the poets themselves, by inviting fifty of them to select and comment upon a poem by another writer.The approaches taken are various, confirming that there are as many ways for a poet to write about someone else's poem as there are poet-poem matches in this volume. Yet a straight-through reading of the fifty poems anthologized here, along with the fifty responses to them, emphatically demonstrates the importance to poetry of community, of socioaesthetic networks and lines of connection, and of expressions of affection and honor due to one's innovative colleagues and predecessors. Through the curation of these selections, Filreis and Safford express their belief that the poems that are most challenging and most dynamic are those that are open—the writings, that is, that ask their readers to participate in making their meaning. Poetry happens when a reader and a poet come in contact with one another, when the reader, whether celebrated poet or novice, is invited to do interpretive work—for without that convergence, poetry is inert.

Frequently asked questions

Information

1 Divya Victor

Twenty-eight young men bathe by the shore,Twenty-eight young men, and all so friendly,Twenty-eight years of womanly life, and all so lonesome.She owns the fine house by the rise of the bank,She hides handsome and richly drest aft the blinds of the window.Which of the young men does she like the best?Ah the homeliest of them is beautiful to her.Where are you off to, lady? for I see you,You splash in the water there, yet stay stock still in your room.Dancing and laughing along the beach came the twenty-ninth bather,The rest did not see her, but she saw them and loved them.The beards of the young men glisten’d with wet, it ran from their long hair,Little streams pass’d all over their bodies.An unseen hand also pass’d over their bodies,It descended tremblingly from their temples and ribs.The young men float on their backs, their white bellies swell to the sun, they do not ask who seizes fast to them,They do not know who puffs and declines with pendant and bending arch,They do not think whom they souse with spray.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Divya Victor: on Walt Whitman, Canto 11 from “Song of Myself”(1855)

- 2. Rae Armantrout: on Emily Dickinson, “The Brain—is Wider than the Sky” (c. 1862)

- 3. Ron Silliman: on Gertrude Stein, “A Carafe, that is a Blind Glass” (1914)

- 4. Bob Perelman: on Robert Frost, “Mending Wall” (1914)

- 5. Rachel Blau DuPlessis: on H.D., “Sea Rose” (1916)

- 6. Yosuke Tanaka: on Ezra Pound, “The Encounter” (1916)

- 7. Christian Bök: on Marcel Duchamp and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, “Fountain” (1917)

- 8. Tonya Foster: on Claude McKay, “If We Must Die” (1919)

- 9. Lytle Shaw: on Wallace Stevens, “The Snow Man” (1921)

- 10. Julia Bloch: on William Carlos Williams, “The rose is obsolete” (1923)

- 11. Jennifer Scappettone: on Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, “XRAY” (1924)

- 12. Craig Dworkin: on Bob Brown, from GEMS (1931)

- 13. Rodrigo Toscano: on Genevieve Taggard, “Interior” (1935)

- 14. Mark Nowak: on Ruth Lechlitner, “Lines for an Abortionist’s Office” (1936)

- 15. Robert Fitterman: on Mina Loy, “The Song of the Nightingale Is Like the Scent of Syringa” (c. 1944)

- 16. Davy Knittle: on Allen Ginsberg, “A Supermarket in California” (1955)

- 17. Jake Marmer: on Bob Kaufman, from “Jail Poems” (1960)

- 18. Danny Snelson: on Jackson Mac Low, “Call me Ishmael” (1960)

- 19. Fred Wah: on Robert Creeley, “I Know a Man” (1962)

- 20. Marjorie Perloff: on Frank O’Hara, “Poem (Khrushchev is coming on the right day!)” (1964)

- 21. Aldon Lynn Nielsen: on Langston Hughes, “Dinner Guest: Me” (1965)

- 22. Sina Queyras: on Sylvia Plath, “Lady Lazarus” (1965)

- 23. Herman Beavers: on Gwendolyn Brooks, “Boy Breaking Glass” (1967)

- 24. Gabriel Ojeda-Sagué: on Barbara Guest, “20” (1968)

- 25. Tyrone Williams: on Amiri Baraka, “Incident” (1969)

- 26. Sarah Dowling: on Lorine Niedecker, “Foreclosure” (1970)

- 27. Michael Davidson: on Larry Eigner, “birds the” (1970)

- 28. Christie Williamson: on Tom Leonard, “Jist Ti Let Yi No” (c. 1974)

- 29. Laynie Browne: on Bernadette Mayer, “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” (1976)

- 30. Charles Bernstein: on Lyn Hejinian, from My Life (1980)

- 31. Al Filreis: on Cid Corman, “It isnt for want” (1982)

- 32. Adam Fitzgerald: on John Ashbery, “Just Walking Around” (1984)

- 33. Stephen Collis: on Susan Howe, from My Emily Dickinson (1985)

- 34. Nick Montfort: on Rosmarie Waldrop, “A Shorter American Memory of the Declaration of Independence” (1988)

- 35. Eileen Myles: on James Schuyler, “Six Something” (1990)

- 36. Simone White: on Erica Hunt, “the voice of no” (1996)

- 37. Mónica de la Torre: on Erica Baum, from Card Catalogues (1997)

- 38. erica kaufman: on Joan Retallack, “Not a Cage” (1998)

- 39. Lyn Hejinian: on Lydia Davis, “A Mown Lawn” (2001)

- 40. Elizabeth Willis: on Rae Armantrout, “The Way” (2001)

- 41. Sharon Mesmer: on Michael Magee, from “Pledge” (2001)

- 42. Rachel Zolf: on Eileen Myles, “Snakes” (2001)

- 43. Edwin Torres: on Anne Waldman, “Rogue State” (2002)

- 44. Amber Rose Johnson: on Harryette Mullen, “Elliptical” (2002)

- 45. Jena Osman: on Caroline Bergvall, “VIA” (2003)

- 46. Imaad Majeed: on Charles Bernstein, “In a Restless World Like This Is” (2004)

- 47. Bernadette Mayer: on Laynie Browne, “Sonnet 123” (2007)

- 48. Douglas Kearney: on Tracie Morris, “Africa(n)” (2008)

- 49. Tracie Morris: on Jayne Cortez, “She Got He Got” (2010)

- 50. Erica Hunt: on Evie Shockley, “a one-act play” (2017)

- List of Contributors

- Index