![]()

Chapter 1

The Geluk School’s Innovative Use of Monastic Constitutions

By 1642, the Fifth Dalai Lama had forged an unparalleled priest-patronage relationship with the supreme political and military presence in Tibet, Kökenuur (in today’s Qinghai Province), and Züngharia (in today’s Xinjiang)—the Oirats or “Western Mongols”; specifically, the Zünghar and Khoshud tribes. From this relationship the Geluk school of Buddhism became reified in an unprecedented way and came in the subsequent centuries to dominate the religious landscape of Tibet, Mongolia, and even the Qing imperial court. One could imagine that this relationship and profound support accorded the Dalai Lama might have led to different historical trajectories. For instance, the Dalai Lama might have chosen to utilize a mobile court like that of the “great encampment” (T. sgar chen) of the Karma school or of the (later) lama Chagan Nom-un Khan in Kökenuur.1 His very mobility, so characteristic of lamas throughout the centuries,2 would have underscored his charisma and the importance of his personal lineage as the center of his religious and political rule. Flocks of disciples and devotees might have followed him, inhabiting makeshift huts (T. spyil pu) along the way, in the hope of receiving teachings, blessings, and empowerments that he would transmit from centuries past. Meanwhile, he would establish separate “teaching centers” (T. bshad grwa) and “practice centers” (T. sgrub sde) for intimate and focused study and meditation. His influence and domain would thereby grow in a more or less piecemeal and organic manner based on the places he traveled to and the personal interactions he had.

So, why did the Dalai Lama choose not to grow his brand of Buddhism in this manner? One monastic constitution that reflects an early move toward institutionalization provides an explanation: “The happiness of society3 depends upon the Teachings of the Buddha, and the Teachings [depend upon] centers of the sangha. Those, moreover, depend upon the firm establishment of order. Even if there is a large sangha, without order, it is of no benefit other than causing great destruction to the Teachings.”4 That is, bigger is not necessarily better. A bigger sangha that is not regimented is actually a detriment to upholding and promoting the Buddha’s Teachings.

The Dalai Lama chose regimentation and order. He took up residence in the Potala Palace at the top of the legendary Red Hill in Lhasa,5 and he was disassociated from any particular monastery.6 The order, or school, that he helped to shape, the Geluk, was not (like the Sakya or Kagyü) associated with a particular place nor even with the Dalai Lama himself. The Geluk school did not depend on a single monastic seat. One might say that it had three seats (T. gdan sa gsum)—the renowned Ganden, Drepung, and Sera Monasteries—but it would be more accurate to understand the Geluk school as an ideology grounded in a system of monasteries and an ideal of proper monasticism.7 The inter-or pan-regional Mongol patrons presented the Dalai Lama and other Geluk prelates with the opportunity to devise a resilient religious group not tied to either a particular place or a particular lineage. Instead, what tied the Gelukpa together was its consistent messaging on the importance of monastic discipline and on its position that scholasticism and scriptural authority takes precedence over claims to insight grounded in meditative practices alone.

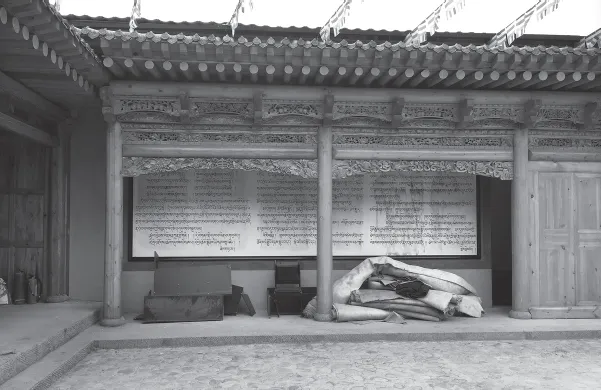

A primary medium of this messaging was the monastic constitution, or chayik (bca’ yig) in Tibetan.8 Short for “trimsu jawé yigé” (T. khrims su bca’ ba’i yi ge), “documents that institute as law,” these documents were and continue to be important for providing monasteries with a blueprint for how the monastery should ideally operate.9 In addition, they provided legitimacy to the administrative structure of the monastery. Usually an illustrious lama would be sought out and even beseeched by the elder monks and administrators of a monastery to compose a constitution for the institution, which would lend the monastery legitimacy. Occasionally, these documents would be put on display on a monastery wall, although more often they were written on scrolls similar to secular legal documents.10 The monastery’s abbot or senior disciplinarian would act as the custodian of this precious document, regularly revealing it and giving “disciplinary sermons”11 based on it throughout the year. This further legitimized the monastery’s administrative structure and practices by repeatedly appealing to a code of conduct and foundational document12 that transcended the interests of any individual administrator.

Figure 2. A monastic constitution written on the wall of Zaplung Monastery (T. Zab lung rdo dkar bkra shis ’khyil) in eastern Amdo.

Photo by the author, July 2016.

As mentioned in this book’s Introduction, neither the Dalai Lama nor the Geluk school invented the monastic constitution. The earliest extant constitution dates from an itinerant religious community of the eleventh century that was built around the influential figure known as Rongzom (1042–1136).13 In addition, non-Geluk schools of Buddhism, especially the Kagyü school, are responsible for at least twenty extant constitutions dating from before the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama and the climatic growth in monasteries discussed in the Introduction.14 Nonetheless, both a synoptic view of all of the available constitutions as well as a close reading of all of the constitutions through the middle of the eighteenth century reveal that the Geluk school seized the genre of monastic constitutions in ways that other schools only belatedly learned to do.

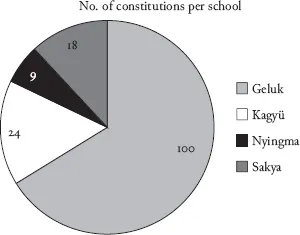

A representative survey of 151 extant monastic constitutions dating from prior to the twentieth century reveals that two-thirds (n = 100) were composed by figures primarily associated with the Geluk school.15 Geluk hierarchs dominated the production of monastic constitutions, particularly from the time the Fifth Dalai Lama assumed power through the first half of the eighteenth century, a period during which they composed almost 90 percent of the extant constitutions. After that, in the latter half of the eighteenth-century, non-Geluk authors doubled the rate at which they had been producing constitutions. Nonetheless, Geluk constitutions are still predominant, and Geluk authors, too, increased their rate of production.16

Figure 3. Representative sample of constitutions broken down by school.

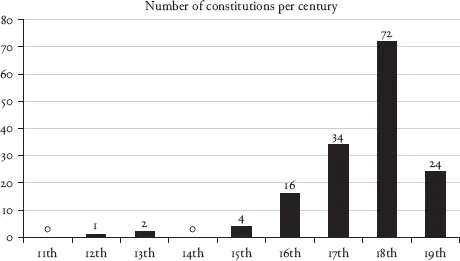

This growing interest in codifying the organization of monasteries in the mid-eighteenth century took place precisely at the moment that the influence of Central Tibetan hierarchs in Amdo began to wane.17 This is also the period during which monasteries in Inner Mongolia were being founded at a historic rate.18 In other words, the surge in the production of Geluk constitutions in the latter half of the eighteenth century reflects the institutionalization of the Geluk school beyond Central Tibet. After the death of the Fifth Dalai Lama, many of the constitutions that were composed were for monasteries on the frontier of Tibet, especially in Amdo (constitution nos. 58, 60–61, 65–67, and 69). Not only that, but they were also being composed increasingly by Geluk hierarchs from the frontier for monasteries in Amdo and beyond in Mongolia. Later still, we find Mongol authors of monastic constitutions, such as the Eighth Jibzundamba (1870–1924), who wrote at least three Tibetan-language constitutions.19 The most prolific author of monastic constitutions prior to the twentieth century was the Second Jamyang Zhepa (1728–1791; nineteen constitutions), who was the principle lama of Amdo’s major Labrang Monastery. This shift in the locus of Geluk power from Central Tibet to Amdo—or, more precisely, the decentralization of power and its distribution into bureaucratic institutions—is connected to similar observations that have been made regarding a geographic shift in the production of collected works20 and in the phenomenon of finding and recognizing the rebirth of an important religious master in a young child.21

Figure 4. Representative sample of constitutions broken down by century of composition. This demonstrates the tremendous growth in production that coincided with the Geluk school’s coming to power and spreading across the Tibetan Plateau and into Mongolia.

In addition, this surge in the production of constitutions is an outgrowth of a standardization that was initially worked out by the Fifth Dalai Lama and other Geluk hierarchs in the decades immediately following his death. The Fifth Dalai Lama is the second most prolific author (after the Second Jamyang Zhepa) of constitutions prior to the twentieth century (eighteen constitutions), and, as I will show in later chapters, the influence of his constitutions on the language and content of the constitutions that followed is clear. Constitutions prior to the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama were mostly composed for “retreats” or “hermitages,” and as such included (among other things) a preoccupation with maintaining the “boundaries” (T. mtshams; Sanskrit sīma) of the retreatants, with limiting their possessions, and with stressing the importance of meditation. The communities for which these constitutions were composed were relatively “guru-centric,” being communities built around the charismatic personality of an individual or an individual lama lineage. The constitutions for these communities also exhibit a greater emphasis on the secret “commitments” (S. samaya) that bind together a “tantric family.” And, significantly, they were composed by a lama for his own community.

In contrast, later constitutions—those composed by the Fifth Dalai Lama and by other Geluk hierarchs in the early decades of the eighteenth century—reveal concerted attempts to codify certain institutional arrangements: seating, debate topics and scholastic curricula, granting of degrees, ritual manuals to be consulted, requesting and granting of leaves, limiting and channeling the collection of “alms,” the redistribution of “alms” (usually making it more equitable), the responsibilities of officers, and so on. We see a greater emphasis on the importance of impartiality among officers. These constitutions also sometimes make explicit reference to other, more centrally located monasteries (or to “mother monasteries”) as models. And, finally, these constitutions were often composed for monasteries far away (often on the frontier with or in Mongol areas) that did not necessarily share any historical or institutional affiliation with the lama tasked with composing the constitution. The Gelukpa were doing something qualitatively different than earlier authors.

A review of the extant monastic constitutions reveals the opportunism of the Geluk school. As the Gelukpa consolidated their control in Central Tibet and expanded it into new areas, they used the power of the written word in a variety of ways to establish and legitimate their authority.22 One such way was their prolific production of monastic constitutions. The expanding political and spiritual horizon afforded by the Geluk alliance with the Khoshud and Zünghar Mongols and, a little later, the Manchu Qing Empire, and a compulsion to fulfill the prophecy that “the Buddha’s Pure Religion”—particularly that of the “Second Buddha,” Tsongkhapa—“will spread in the East”23 led to the creation of mega monasteries across the landscape of Inner Asia and to the success of the Geluk school.

Retreats and Places of Practice

I have attempted to gather and read every available constitution through the 1740s, which amounts to nearly seventy constitutions,24 and more than a dozen from after this period. The period between 1642 and the 1740s was the period during which the Geluk school co...