![]()

1

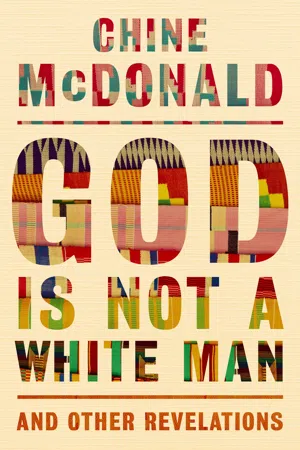

God Is Not a White Man

I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background . . . Among the thousand white persons, I am a dark rock surged upon, and overswept, but through it all, I remain myself. When covered by the waters, I am; and the ebb but reveals me again.

Zora Neale Hurston, How It Feels to Be Colored Me1

The first time I encountered God in my likeness was in a shack. Like millions of others, I had been reading The Shack – the New York Times bestselling novel by Canadian author William P. Young. It tells the story of a man who, torn apart by grief after an unspeakable tragedy, encounters God in three persons in a shack in the middle of nowhere. God is represented by the Holy Spirit in the form of an Asian woman; Jesus, in the form of a Middle Eastern man; ‘Papa’ – God the Father – in the form of a curvy Black woman. Those who had read the book were careful not to give spoilers, so when I encountered Papa in the pages of the book, I was left open-mouthed. Never had I imagined that God could be portrayed in this way. I remember calling my mum, who had read the book before me. We were excited, overwhelmed, yet also rendered speechless. God looked just like us.

When the Hollywood film came out a few years later, God the Father was played by Octavia Spencer, who, ironically, had played maid Minny Jackson in the civil rights film The Help. Seeing her on screen brought it home to me even more. Here she was, a beautiful, curvy Black woman playing the Almighty. It’s hard to describe what this meant to us. It was not something we had ever called for or even consciously thought about, but there was something liberating in seeing – even for that short period – a God in whom we really saw ourselves.

It had never occurred to me that Jesus wasn’t white. By the time I woke up to this fact, it was far too late to reconfigure the image that I had of God in my mind. To this day, when I picture Jesus, I think of a piercing-blue-eyed man with a brown beard and sandy, neck-length hair. I can see him now. He looks like Robert Powell did in the 1977 Jesus of Nazareth film. He does not look ordinary, but he does look white. At times when I have pictured Christ on a cross, cried out to him in my darkest moments, prayed to him for those things I have desired most, sung praise to him in worship, I have pictured a man who never existed. The Jesus I have clung to is a falsehood, a symbol created by the effect of white-supremacist fiction. God is not a white man. This revelation is painful and brings with it a realisation that white supremacy has found its way into the most sacred place. Although painful, however, the realisation that Jesus was not white has brought with it a profound sense of liberation.

For women in general, and women who are not white in particular, White Jesus has been distant, unable to represent us. And it has been difficult for us to see ourselves represented in him. We know the incarnation – God becoming human – meant that Christ would have had to take one form only, so perhaps, some might argue, it may as well have been the form of a man – especially given the positions women occupied in first-century Roman-occupied Palestine. But, throughout history, the Church has overplayed this fact and used it to exclude women from positions of power and leadership, and even salvation.2

For years, there has been a movement of feminists who question the masculine pronouns we use for God; for God, of course, is neither male nor female. The Bible uses a number of different masculine and feminine metaphors to describe God. While intellectually I know that God is not a man, it takes a huge amount of effort to picture God differently and to find alternative words to describe . . . him. But yet I know the importance of trying to do so. It is important that I liberate God in my mind from the limited man-shaped box in which I have placed the divine. I am used to using male pronouns to describe God, but I have chosen in this book to practise what it feels like to not describe God as male.

God is not a man.

And neither is God white. For some, this fact seems just as difficult to grapple with as the idea that God is not a man. Most who have read the Bible or know any part of its history – whether they believe in Jesus or not – know that the incarnate God in human form would have looked like a man from what we have come to call the Middle East, born in Bethlehem. I have been fortunate enough to visit that wonderful holy place and meet its people – each a different shade of brown. The Jesus I picture looks nothing like them. He looks like an American hippie from the 1970s.

The painting Head of Christ might have something to do with this. It depicts an image we have come to understand as representing the archetypal Christ. It’s Jesus, but with an extra dash of U-S-A. His dark-blonde wavy hair, his perfectly shaped beard and his piercing eyes staring up at something in the distance. The light of a lamp or a candle illuminates the background. Created in 1940, the striking image has been described as one of the best-known American pieces of art of the twentieth century and reproduced more than 1 billion times worldwide, although its creator Warner Sallman’s name is less well known than his most famous painting.

Sallman was a commercial artist, based in Chicago, who had grown up in the Evangelical Covenant Church. The first iteration of what was later to be known as the Sallman Head was created in 1924 as a charcoal sketch for the front cover of a Swedish Evangelical Mission Covenant youth magazine, Covenant Companion. He wanted it to appeal to young people and so gave it the feel of a school photograph – I guess the type we have become familiar with seeing in yearbook photos from American high-school films. People loved the image so much that the magazine sold every one of its 7,000 copies, and then Sallman paid for an additional 1,000 copies to be printed, which were also sold over the following years. The image stayed popular over following years, until in 1940 a group of graduating students at North Park Theological Seminary in Chicago commissioned him to create a painting based on his charcoal drawing to give as a gift to their school.3 This image was even more popular than the original and began to be reproduced around the country. In 1941, when the United States joined the Allies in World War II, chaplains and religious leaders gave servicemen pocket-sized versions of Sallman’s image. Despite its humble beginnings, Head of Christ is one of the most famous pictures on the planet.

Some might wonder why this is an issue, but its popularity is precisely what makes it problematic. White Jesus is the logical consequence of a world that values whiteness as supreme. Sallman’s Head of Christ is, of course, not the only depiction of Jesus resembling a white European. This is the form that has become most recognisable to people across the globe for centuries.

The archetypal depiction of Jesus we see today is thought to have originated in the fourth century, during the Byzantine era, when the image of an enthroned emperor with long hair and beard came to be the predominant way of representing Jesus. Much later on, this evolved into the more hippie-like representation of Jesus we see today.

White Jesus is the consequence of a number of Western historical, theological and sociological prejudices that were so fundamental to the notion of white superiority that Christ could not have been anything but. One of the main factors, argues theologian Shawn Kelley, author of Racializing Jesus,4 is that eighteenth-century German theologians argued among themselves about the ideas that, on one hand, Christ was ordinary and, on the other hand, he was completely otherworldly. I remember my first introduction to ‘the historic Jesus’ during lectures on Christology at university. As an eighteen-year-old, who had grown up in conservative evangelicalism, I found shocking the idea that Jesus was in many ways ordinary. Placed within the historical context of first-century Palestine, Jesus ‘could be seen as an essentially Jewish figure whose teachings were in line with those of other Jewish sages of the time’.5 Those who wanted to downplay the ordinariness of Jesus and elevate his unique divinity subsequently became more ‘anti-Judaism’. Some theologians sought then to offer various solutions that stood Jesus apart from his Palestinianness and his Jewishness. This led to the idea that instead Jesus was in fact racially Aryan – set apart from his Jewishness and his so-called ordinariness. So White Jesus became a way of emphasising Christ’s divinity, as distinct from the brownness of his historical context.

It wasn’t until I watched the BBC documentary Son of God6 when I was a teenager that I properly took notice of the fact that the representations of Christ so ingrained in my mind did not reflect the historical reality of his probable appearance. In the programme, anthropologist Richard Neave used a skull found in the region of Galilee to create a model of what Jesus might have looked like. What they came up with was not beautiful by the Western standards we have been conned into thinking are objective. Since nowhere in Scripture does it actually suggest that Jesus was physically different from those around him, we can assume that he looked similar to the average Galilean man of his day, and so we can accept that he probably did look more like Neave’s reconstruction than Hippie Jesus.

The most famous artworks picturing Jesus – from Salvador Dali’s Christ of St John of the Cross to Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World to Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi – depict him as white, with long hair and a beard. This image is the only one I have of Jesus – a consequence of having seen thousands of images of Christ represented in this way throughout my life. Unseeing and reimagining White Christ in the minds of believers is almost impossible. In a world where whiteness is power, then, of course an omnipotent, all-knowing God must be white. God could be nothing else. Robert P. Jones writes, in White Too Long, that the emphasis on a personal relationship with Jesus that is front and centre in white evangelicalism only served to cement the depiction of Christ as white.7 While one of the main tenets of Protestant Christianity is this idea that humans do not require a church or priest as mediator in order for them to have a relationship with God, modern Western evangelicalism can at times give the impression that this relationship with Jesus is like one we might have with a brother, or even a boyfriend. As Jones puts it,

White Jesus, Trump and Evangelicalism

On 6 January 2021, I watched as a mob of angry white men stormed into the Capitol Building in Washington, DC – a symbol of democracy not just in the US, but around the world. They smashed windows, attacked police officers and wrote the words ‘Murder the media’ on government property. The attack took place while US lawmakers were voting to confirm the election of Joe Biden. It was this fact that the angry group of nationalists were refusing to accept and fighting against, having been incited by Trump, believing that the election had been stolen from them. We would hear later that US lawmakers were forced to cower in place, some barricading themselves into their offices, some calling their loved ones to say goodbye, some praying. I felt a sense of cognitive dissonance as I watched live as this armed insurrection unfolded.

Before the election of Donald Trump, such a scene would have seemed inconceivable even in a fictional TV series. What was so disturbing was the clear sense of entitlement among the rioters, who seemingly did not fear that they would face opposition from law enforcement or be met with any consequences. The fact that rioters filmed themselves and posted selfies on social media showed how little they feared being held to account for what they had done. As people around the world watched, most of us expected that at any moment the National Guard or the army would appear en masse to put the riot to a stop. But this took far too long. The crowd only seemingly decided to end their insurrection when Donald Trump posted a video telling them to go home – not without adding that they were ‘very special’ and that he loved them.

It’s hard to describe the sense of injustice that I felt as a Black person – even one living thousands of miles away from where the insurrection was taking place. I contrasted this unbelievable scene with the historic images imprinted in my mind of Black people protesting peacefully and being met with unimaginable violence – tear gas, beatings, murder. I only had to think to a few months earlier when Black Lives Matter protestors, whose demonstrations had been overwhelmingly peaceful,9 faced heavy-handed treatment from the police. The Capitol Hill insurrect...