![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: Reframing Parking Requirements as a Policy Choice

Parking requirements stand in the way of making cities livable, equitable, and sustainable. This is because parking is a prodigious and inefficient consumer of land. If parking was a person we might say that s/ he is very poor at multitasking. Parking serves one type of transportation—the private vehicle—and uses more land or building area per trip served than any other travel mode. Weekly farmers markets notwithstanding, parking is rarely used for any other purpose. Frequently, parking requirements define urban design, land use density, and experience of place outcomes more than any other zoning regulation. Indeed, meeting parking requirements is often the pivotal factor in project feasibility analysis. Finally, parking serves a travel mode that is energy intensive, polluting, and unavailable to those who cannot drive or afford a vehicle. Recently, a colleague related a story about a regional government that was developing growth scenarios, building upon local zoning information to determine build-out potential. The modelers were surprised to learn that parking requirements, not building floor area ratios or height limits, were the primary determinant of development intensity. When it comes to planning and development, parking is too often the tail that wags the dog.

This book explains why that is the case and provides guidance on reforming parking requirements. It addresses the technical, policy, and community participation aspects of parking requirement reform, seeking to place that reform at the top of the priority list for city officials, politicians, and community members. While the book addresses many aspects of parking requirements, its focus is on reforming minimum parking requirements, the local regulation that compels developers to provide specified amounts of off-street parking.

Although one might be tempted to consider US metropolitan areas as mostly built out, Nelson (2004, 8) projects that half the built landscape in 2030 will not have existed in 2000—there will be 213.4 billion square feet of new built space, reflecting growth and replacement of existing buildings. Reforming parking requirements now is an essential task in making sure the next half of US built form supports broad community goals. The urgency for reform is even greater in developing countries that are experiencing rapid growth, urbanization, and increasing vehicle ownership rates.

Most minimum parking requirements drive up the amount of land and capital devoted to parking. Since private vehicles spend more time parked than they do driving, it is not surprising that there are more spaces than cars in the United States. At this moment, my car is parked at my home office, but there are unoccupied spaces waiting for it at my job, the shopping mall, the donut shop, and the funeral parlor. The total amount of parking in the United States is difficult to estimate, since it involves estimates of parking in private residential garages; along street right-of-ways; and in surface, structure, and underground facilities. Chester, Horvath, and Madanat (2010) review the literature and conclude that the most defendable estimates are between 820 and 840 million parking spaces in the United States, or about 3.4 spaces per vehicle—and many more parking spaces than people. The researchers also calculate the impact of parking in the lifecycle performance of various types of private vehicles, finding that parking adds between 6 and 23 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per passenger kilometer traveled.

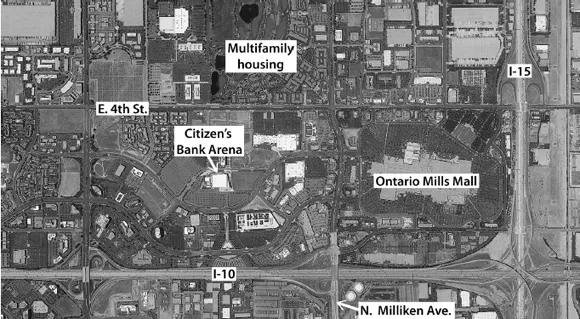

If there was any doubt about the effect of parking requirements on urban form, the images in figures 1.1 and 1.2 display the consequences. They show a suburban area located at the intersection of the I-10 and I-215 freeways in the eastern portion of Southern California known as the Inland Empire. The aerial view provided in figure 1.1 reveals a mix of commercial, entertainment, office, residential, and recreational uses in the cities of Ontario and Rancho Cucamonga. This ample parking provides convenient and accessible parking for residents, employees, and shoppers, supporting their decisions to travel using private vehicles. At the moment the image was taken, much of the parking is empty, revealing a wasteful use of land made clear in the pedestrian eye view in figure 1.2. The primary reason for this waste of land is that land uses have different peak times of occupancy, yet the common practice in minimum parking requirements is to compel each use to provide more than enough parking for its own peak utilization period, as if it is a parking “island” with no ability to share with other uses. This parking oversupply is not limited to suburban areas. The city of Seattle surveyed neighborhood parking occupancy (on- and off-street) and found that peak period parking occupancy was generally below 75 percent of supply (City of Seattle 2000). Collectively, this aggregate oversupply of parking produces negative consequences that are described in chapter 2.

Contrast those suburban images with a parking solution adopted in an older urban area. Figure 1.3 shows an image from a street in Boston where parking in the middle of the street (apparently in both directions) is allowed on Sunday mornings (only!) to accommodate churchgoers. This neighborhood was built before parking requirements existed, and therefore it has a parking “problem.” This “middle of the street” solution goes against most conventional parking principles, such as avoiding traffic flow disruption and preventing pedestrian/vehicle interaction. Yet the community has found a way to take advantage of precious urban real estate and tailor a solution to a time-specific problem.

Figure 1.1. The impact of parking on urban form. Image source: Google Earth

Figure 1.2. Underutilized parking at Ontario Mills Mall, weekday

Parking requirements cause more parking to be built than developers would provide if they made the decision on parking supply. If this was not the case, there would be no need for minimum parking ratios. If off-street parking supply was not regulated by zoning codes, developers would assess the degree to which parking adds net value to the development, considering costs, impacts on project revenue, and the opportunity cost of not using land for other purposes. Developers would consider the preferences of tenants and customers in reaching this decision. Opportunistic developers might seek to use on-street and other off-street parking resources to avoid building parking, but this practice is easily prevented through parking time limits, parking pricing, and access rules. By replacing the developer’s analysis with a code requirement, creative ideas such as shared parking are less likely to occur. Of course, some national retailers or office locations, lenders, and institutional investors may require the same amount as code requirements, but my research shows that parking requirements are the most important factor and one that other parties consider in creating their own standards. Developers, lenders, and project designers think local zoning codes “know” the right amount of parking (Willson 1994). We have little knowledge of the amount of parking that developers would provide on their own because it is so rare that a developer has that choice outside central business district (CBD) environments. In those CBD environments, we see innovation in parking provision and a more balanced set of transportation access modes.

![]()

Parking Requirements as Policy

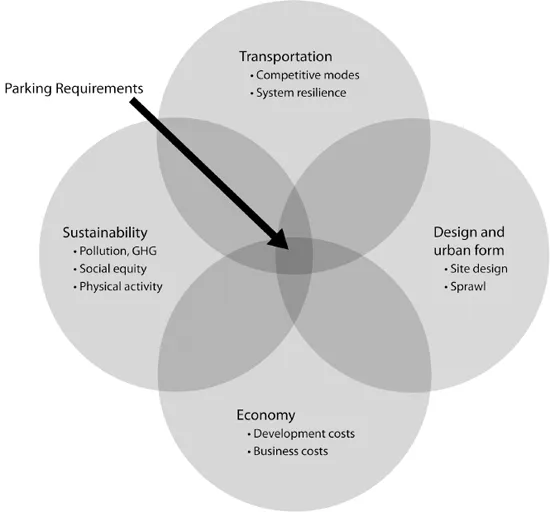

Far from being a technical matter best reserved for traffic engineers, parking requirements are a policy choice that lies at the intersection of land use and transportation planning. As a component of the transportation system, parking provides terminal facilities at the end of each vehicle trip. By favoring private vehicle transportation, parking reduces the competitiveness of other travel modes such as transit. It leads to a one-dimensional transportation system based on private vehicles that is not resilient in the face of disruptions such as energy crises or requirements to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As a land use, parking affects design and urban form by shaping site design, lowering density, and contributing to sprawl. But transportation and land use are not the only policy areas affected by parking requirements. Parking requirements affect economic development by influencing the cost of development, business formation and expansion, and ongoing operations. They determine sustainability outcomes directly (as a land use) and indirectly, by encouraging private vehicle travel and lowering density. Automobile-oriented, lower-density places, in turn, increase air, water, and other forms of pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Parking requirements tilt the playing field in favor of those who can afford to and/ or are able to drive private vehicles. Finally, parking requirements create environments that harm public health by reducing physical activity and increasing pollution.

Figure 1.3. Parking “chaos” in Boston

Figure 1.4 represents these ideas in four overlapping circles. Each circle is a policy domain on its own, but parking requirements link them together in rarely recognized ways. We must enlarge the traditional view of parking as simply a mitigation measure for development to recognize these interconnections.

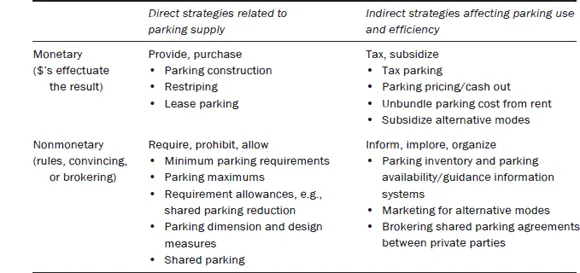

In addition to understanding the policy implications of parking requirements for metropolitan development, there are policy choices in the way we think about addressing parking issues. Table 1.1 shows four ways that a public agency can address parking, drawing on a conceptualization of types of policy actions developed by Patton et al. (2013, 10). The traditional approach is the left-hand side of the diagram, where the jurisdiction either builds public parking or adopts parking regulations that developers must follow, such as minimum requirements or parking maximums. The regulatory mindset in parking is strong, reflected in the sentiment that the developer “owes” the jurisdiction a plentiful parking supply. The approaches in the right column of the table receive less attention, as they use pricing and subsidies to affect parking demand and increase parking use efficiency with information systems. We should recognize that parking requirements are only one tool to solve parking issues.

Figure 1.4. A policy frame for parking requirements

Table 1.1. Alternative public sector parking strategies

Over more than two decades, researchers have revealed the problems with parking requirements, pointing out that they often require more parking than is used and make free parking inevitable. They point out that standardized data sources on parking utilization, such as the Institute of Transportation Engineers Parking Generation handbook (ITE 2010), provide data that is used uncritically and builds in assumptions that parking is free and generously supplied, and that transit is largely unavailable. Parking Generation collects utilization studies from across North America and compiles them into tables that show parking rates for different land uses.

Some jurisdictions have reformed their parking requirements (see examples in chapter 3), but progress is slow in many places. This is because parking requirements often fall between the cracks in understanding and action. In research, parking requirements fall between the fields of land use planning, transportation planning, community development, economics, and civil engineering. In municipal government, responsibility for parking requirements falls between planning, public works, and engineering departments. Planners generally write the codes but they often defer to engineers for technical matters in transportation, including parking requirement ratios.

Progress is also slow because residents, stakeholders, and elected officials are conflicted on the subject. Often they favor mixed-use development, transit, and so on, but when it comes to the essential parking reforms that make those ideas work, they demur. A mitigation mindset, in which all project impacts must be mitigated to insignificance, often includes parking. As a result, the possibility that a project will have less parking than is demanded (when parking is free) is considered an environmental harm instead of a condition that requires parking management and reduces automobile dependence. Also, since most people drive and park, otherwise “green” stakeholders may suffer from a conflict of interest with regard to parking. Facing more expensive parking (the result of tighter supply/demand conditions) may be perceived as a problem rather than a green policy, even though the impacts of less parking might be greater than recycling, organic food, or renewable energy. Over the years, I have met many committed environmentalists who nonetheless want to keep their parking privileges.

Parking requirement reform calls for a new understanding of the relationship between land use and transportation planning. Through the history of cities, innovations in transportation allowed new land use forms to emerge. For example, the electric streetcar enabled suburban expansion and the development of freeways accelerated that trend. In most early transportation planning exercises, land uses beget transportation facilities. In other words, transportation models predicted travel demand based on land use patterns and growth, and transportation planners/engineers sized roadway facilities accordingly. Later, in the era of growth management and environmental impact reports, transportation capacity limited land use intensities. Growth was controlled to match transportation capacity. Now, there is a bidirectional relationship in which new transportation capacity opens up areas for land use expansion and infill, but some development and urban redevelopment is limited by transportation capacity. An integrated approach is needed where reform-minded cities chose policy in both transportation and land use that reinforces desired community goals, such as increasing density or multimodal transportation. For example, a city may adopt plans for dense mixed-use development and new transit options, strategically reducing road capacity at the same time. To support this, parking requirements may be cut, district-level parking supplies may be capped or reduced, and market pricing for parking may be introduced. Local jurisdictions must decide if they are in the “transportation capacity follows land use growth” model or if they are going to deliberately change transportation capacities in search of a new integrated land use and transportation vision.

The conceptual challenges are formidable. The way we think about parking affects the type of solutions we imagine. Figure 1.5 shows that parking requirements are at the bottom of the hierarchy of accessibility goals and implementation techniques. The top of the pyramid is access—the ability to make connections over geographic space—for trips between home and work, work and shopping, and the like. The primary methods of accomplishing access are land use planning, telecommunication substitution, and transportation. Each of those realms has a variety of techniques, with private vehicle transportation being one of many techniques, but not the only one. Vehicle parking, in turn, is an element of a system that provides for private vehicle transportation. Parking requirements, then, are one way of addressing parking supply. Parking supply ...