![]()

Chapter 1

A NEW LIFE

Eleanor Dare, 1580s

Eleanor Dare was well into her third trimester when she arrived on the shores of Roanoke Island in 1587. She, along with over one hundred men, women and children, had set sail from England and endured a three-month ocean passage to reach the “New World.” They came ashore in July, a month that marks the height of summer in coastal North Carolina. Temperatures reach into the nineties; mosquitoes swarm, and high humidity overwhelms. In addition to the exhausting and disorienting effects of travel, Eleanor would have been experiencing intensifying physical symptoms as her body prepared for childbirth—swelling, fatigue, shortness of breath, insomnia and body aches, to name a potential few. While she is memorialized throughout history as the mother of the first English child born in the New World, we don’t often consider the peril she was thrown into on these shores or the tragedy that befell the native inhabitants.

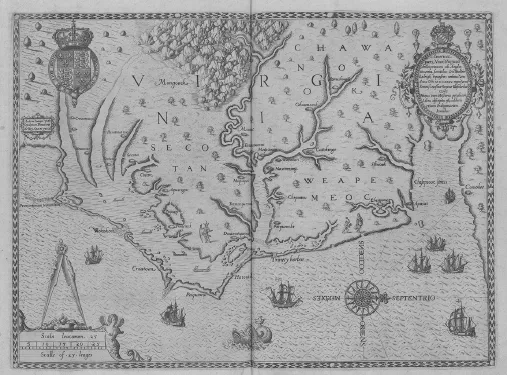

A TIME BEFORE “THE OUTER BANKS”: MAPPING THE CAROLINA SOUNDS IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

In the sixteenth century, the area we now call the Outer Banks was a part of what the English called Virginia, named for their virgin queen, Elizabeth I. It had been “discovered” by the English in 1584 when Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe voyaged on behalf of Sir Walter Raleigh to explore a potential site for an English colony overseas. To the land’s Indigenous inhabitants, the area was known as Ossomocomuck. They were Algonquian-speaking people who naturally “did not consider the place they lived a new world,” as author Michael Leroy Oberg explains in his book The Head in Edward Nugent’s Hand: Roanoke’s Forgotten Indians. His researched narrative centers the Algonquian people in the story of Roanoke Island, shifting the perspective from the English explorers who, despite claiming and naming the land for their queen, “intruded into an environment where Indian rules prevailed.”1

Jill Voight played the role of Eleanor Dare during The Lost Colony’s 1969 season. Here she depicts the young mother on the shores of a strange land. Photo courtesy of the Outer Banks History Center, Aycock Brown Papers.

Ossomocomuck stretched from the border of modern-day Virginia south to Bogue Inlet and included the barrier islands of the present-day Outer Banks to the east and a swath of the coastal North Carolina mainland to the west. The islands, like Roanoke, that lay in the sounds between these two points were included in the domain of Ossomocomuck as well.

Roanoke in particular was named for “the people who rub, abrade, smooth or polish by hand.”2 This likely referred to the shell beads that the island’s inhabitants were known to make and wear. Ossomocomuck was made up of dozens of independent communities, including Roanoke, Croatoan on Hatteras Island and Dasemunkepeuc in modern-day Manns Harbor. Though autonomous, the communities were interconnected and likely all under the authority of an Algonquian leader, or weroance, named Wingina.3 Though it is not widely known or taught, we could point to his tragic end as a catalyst of the demise of the ill-fated 1587 colony on Roanoke Island.

A sixteenth-century map of the coast from Chesapeake Bay to Cape Lookout, made by John White. It shows the locations of Algonquian villages, including “Roanoac.” Photo courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

THE 1587 COLONY WAS BOUND FOR THE CHESAPEAKE BAY

The Lost Colony, an acclaimed outdoor drama that tells the story of Sir Walter Raleigh’s 1587 colony, has been captivating audiences on the Outer Banks since it was first performed in 1937. But the arrival of the colonists on Roanoke Island was not marked by providence as much as this cherished story would lead us to believe. Eleanor Dare and the other men, women and children were effectively stranded on the island when the expedition’s pilot, Simon Fernando, refused to take them any further.

John White, the father of Eleanor Dare, was an artist who had been on previous voyages to Roanoke Island and was appointed governor of the 1587 colony. His watercolors provide an unprecedented glimpse of life on America’s Eastern Seaboard in the sixteenth century, and his journals provide us with a detailed (though one-sided) account of the expeditions to Roanoke Island. His account of the 1587 voyage is fraught with mistrust and disdain for the expedition’s Portuguese pilot, Simon Fernando.

To imagine Eleanor’s discomfort during the long journey is something that none of the existing accounts of the voyage attempt to do. But anyone who has carried a child or been in a close relationship with someone who has can intuit how miserable it likely was for her. On their way to Virginia, their ships stopped in Saint Croix on June 22, where they went ashore for several days. John White wrote in his journal that after eating some type of small green apple, some of the men and women were “fearfully troubled with a sudden burning in their mouths, and swelling of their tongues so big, that some of them could not speak.” Eleanor may have watched in horror as “a child, by sucking one of those women’s breasts, had at that instant his mouth set on such a burning that it was strange to see how the infant was tormented for the time.” White also wrote of the colonists washing in a standing pool of water and that “their faces did so burn and swell that their eyes were shut up and could not see in five or six days longer.”4

With their ships finally anchored off Hatteras, White wrote that on July 22, 1587, he and forty men prepared to sail a smaller ship, or pinnace, to Roanoke Island ahead of the other colonists. Their aim was to locate fifteen Englishmen from the 1585 expedition who had been left there by Sir Richard Grenville, “have conference concerning the state of the Country and savages,” then “return again to the fleet and pass along the coast to the bay of Chesapeake.”5 It was then, as they sailed off from the larger ship, that Simon Fernando called to John White, ordering him “not to bring any of the [colonists] back again, but leave them in the Island,” and declaring that “he would land all the [colonists] in no other place.”6

Simon Fernando was refusing to take them any further. With summer nearing its end, he was anxious to return to Europe to encounter Spanish ships that he might privateer. At least, this was the excuse he gave. He had no apparent interest in the success of White’s colony and effectively stranded the 117 men, women and children on Roanoke Island. It was only ever meant to be a stopover on the way to their final destination on the Chesapeake Bay, where they hoped to establish the first permanent English settlement on the North American continent. While Raleigh’s 1584 and 1585 voyages to Roanoke had been largely military in nature, the vision for his 1587 colony was decidedly different. Chesapeake was chosen as the site for the “Cittie of Raleigh” for its location near a safe, deep-water anchorage where ships could easily reprovision and return to England. Rather than relying on the natives of the land for food, as the previous expeditions had, this colony would be a self-sufficient farming operation. Finally, to ensure the colony’s permanence, women and children were needed. On board the ships were seventeen women and nine children that, along with the men, made up fourteen families. Two of the women, including Eleanor Dare, were pregnant, and from the account on Saint Croix we know of at least one other who was breastfeeding an infant.7

The caption by John White on this watercolor reads, “One of the wives of Wingina.” The hairstyles, dress and ornamentation of the English women would have been very strange to the Algonquian women, and vice versa. Photo courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Sir Walter Raleigh envisioned his colonies in America as philanthropic endeavors that would bring civility, Christianity and other Anglo values to the “savages” that lived there (though competing with the French and Spanish for territory in the New World was certainly a motivator as well). This reveals the assumption of the English that the Algonquian-speaking people who inhabited the Outer Banks were uncivilized and in need of enlightenment or salvation. They, of course, did not view themselves this way. In an act of civility, they initially welcomed the English to the area and invited them to settle on Roanoke, interested in trade and allyship with the strange foreigners.

But what came to pass during Raleigh’s attempted 1585 colony, which was the second expedition to Roanoke Island, deteriorated all hopes of peaceful cooperation and coexistence. In fact, it doomed the next group of outsiders who would set foot on the island, which happened to be the 117 men, women and children of the 1587 colony.

THE DEATH OF WINGINA AND ITS CONSEQUENCES FOR THE “LOST COLONY”

In the summer of 1586, one year before the “lost colonists” arrived on Roanoke Island, Ralph Lane had been left in charge of Raleigh’s 1585 colony while Richard Grenville returned to England for supplies. There was tension between Lane and Wingina, who had recently changed his name to Pemisapan, and Lane suspected that he was conspiring to launch an attack on the colony. While some Roanoke and Croatoan leaders were friendly with the English, Wingina had decided to oppose them. He had initially extended his welcome, but as Lane and his men continued to put a burden on his people’s food supply, took advantage of their generosity and began to demonstrate violence, relations started to degrade. Wingina, now Pemisapan, wished to cut ties with the English, but if anything, he hoped that they might starve and retreat.8 Fearing an attack by Pemisapan’s people, Lane decided to attack them first.

Wingina, who later changed his name to Pemisapan, depicted in a watercolor by John White. He was the leader, or weroance, of a network of Algonquian villages called Ossomocomuck. Photo courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Lane started by attacking the few Algonquians that remained on Roanoke Island. Most of them had relocated to Dasemunkepeuc across the sound (in modern-day Manns Harbor) shortly after Lane and his men built their fort on Roanoke Island. So that word of the attack would not reach Pemisapan in Dasemunkepeuc, Lane sent some of his men into the Croatan Sound by night to intercept anyone who might be rowing back there from Roanoke. When the Englishmen encountered a canoe carrying two survivors, they overtook the Algonquians and cut off their heads. Word of Lane’s attack never reached Pemisapan.

The next day on June 1, 1586, Pemisapan welcomed Ralph Lane and his men when they arrived at Dasemunkepeuc and waited for them to state their purpose. The English then opened fire, and Pemisapan was hit by a shot from a pistol. He fell to the ground, where the English assumed him dead. They continued to attack his people, as well as friendly Croatoans from Hatteras Island who often spent time at Dasemunkepeuc. Lane tried to avoid the Croatoans, but his men were indiscriminate in their assault.

Then, to Lane’s surprise, Pemisapan “started up and ran away as though he had not been touched.”9 One of the soldiers fired a shot at the weroance that hit him in his rear, but he managed to escape into the woods. One of Lane’s men, named Edward Nugent, chased after him and was gone a long time. Fearing that he had been overtaken or ambushed in the woods, the Englishmen went to search for Nugent. After a short while, they found him walking back out of the woods. He held in his hand the decapitated head of Pemisapan. Lane and his men returned to their fort on Roanoke, where they impaled the head of the weroance formerly known as Wingina on a pole.10

It was into the shadow of this vile attack that the 1587 colony came ashore one year later. Eleanor Dare was expecting her baby in a matter of weeks, a child that would be born in hostile territory due to the previous actions of her own countrymen. Lane’s colony had doomed relations with the native people in the area for any Europeans that might come after them. Yet the story of Wingina’s beheading and how it steered the course of the lost colonists’ fate is often overlooked. Oberg writes:

Telling this story forces us to consider the question of just what constitutes a historically significant event, and who decides and why. The brutal act of violence executed by Edward Nugent is almost never specifically mentioned in history textbooks. His name, and that of the weroance he beheaded, are not commonly known. The crime, it seems, has been erased and silenced and forgotten, deemed not relevant to the larger narrative of American history. But the killing of this Algonquian leader had important consequences for the native peoples of the Carolina Sounds, and the short-lived English attempts at settlement brought misery and suffering that are difficult to imagine.11

IN THE WAKE OF A HURRICANE: RALPH LANE’S EARLY DEPARTURE FROM ROANOKE

After beheading the Algonquian leader, Lane and his men made a hasty retreat. Real...