WHY: health

Universals are notoriously hard to pin down. Sustainability, justice, innovation, love, well-being: globally, these are pervasive and honored concepts; yet in the practices, traditions, expectations, and ways of knowing that characterize actual places, they manifest differently. “Health” is an important concept for global sustainability and urban development because so many of the behaviors and interactions realized in spaces bear directly on the mortality and well-being of humans and other species (Hodson, 2016; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al., 2016; Stimson, 2013). As an organizing universal, “health” also leaves itself open to various interpretive moves; yet, two aspects of its definition show real traction and promise for the policy and practice of sustainable development.

First, health can be conceptualized through an easily recognizable and measurable set of characteristics. Bio-function provides some degree of clarity around what sustainability looks like, or at any rate reasonably reliable proxy measures for what it might mean for different organisms and systems and how it can be supported, protected, enabled, and enjoyed. Understandings of species and habitat health inform practices such as adaptive management and ecosystem services, with sophisticated, evidence-based approaches for plant and animal communities experiencing different phases or challenges. Humans who are in stages of rapid brain development, or reproducing offspring, or recovering from disease, or immunocompromised require particular conditions in order to survive and thrive. An ecology that supports health will be one that recognizes, delimits, and nourishes the sources of metabolic and cell-renewing energy for organisms within it. For humans, this may involve complex choices and trade-offs, which is a different constraint than the presence or absence of empirical knowledge that permits such prioritizations. Managing for health may be one of the most profoundly human pursuits we are designed to undertake, for ourselves and in coordination with others (Lee, 2014; Nunes et al., 2016; Petrini, 2010). If a frequent and merited critique of the sustainability movement is its lack of substantive heft (“Sustainability of what? Whose values? Which power dynamics? Why?”) (Littig & Griessler, 2005; Long, 2014; While et al., 2004), then the centering of health as an outcome to be sustained helps provide tangible ways of defining what is needed, for whom, and why. Critically, it puts front and center the understanding that human health relies on symbiotic relationships with non-human species.

Second, perhaps counterintuitively but crucially for the social ecology of urbanizing regions around the Pacific Rim, health permits a broad understanding of its drivers and causal pathways (Grzywacz & Fuqua, 2000; Stokols, 1996). Public health has moved decisively in the direction of acknowledging the social determinants, environmental conditions, and community mechanisms impacting individuals’ medical status, physical vitality, and overall longevity (Corburn, 2017; Schulz & Northridge, 2004). Embraced by the World Health Organization as the “non-medical factors that influence health outcomes”, social determinants of health include economic status, education, nutrition, shelter, interpersonal relationships, and access to basic amenities (Marmot et al., 2008; WHO, 2013). Importantly, inclusion and non-discrimination, as well as the absence of structural conflict are key components of healthy living conditions for human beings, connecting medical science and social science in our understanding of health outcomes. The natural and built environments shape experience, exposures, and resource availability for most people, making the physical support systems of cities and their surrounding landscapes central to the health of those who live there, and underpinning WHO’s holistic and multifaceted approach to health through “healthy settings” (WHO, 1986). Distribution of opportunity and resources will affect who gets and remains healthy, and thus relates to broader goals of environmental justice and global equity. Sustainable development is conventionally constructed around the “three E’s” of economy, environment, and equity; however, human health and health outcomes, as well as those of plants and animals within the systems where we share and depend upon resources, provide a unifying focus that has somewhat eluded sustainability policy and practice over the last several decades (Friel et al., 2011; Kjellstrom & Mercado, 2008).

In the near future, we expect health promotion and health equity to take up larger roles in the political discourse and planning implementation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations in 2015. Since the cholera epidemic of the mid-nineteenth century led to the first collective reckoning in the US with the public interest in water and wastewater infrastructure, the intertwining of public health with urban planning and development has expanded to improving urban parks and green space, regulating urban land use through building and zoning codes, and more recently promoting more walkable places. At the current moment, scientifically unifying, and experientially integrating, global public health has perhaps never seemed quite as personally relevant, politically resonant, and generally ascendant in the public imagination as it does in the midst of a devastating worldwide pandemic. The COVID-19 illness caused by coronavirus infections killed over three million people, with some estimates between 7 and 13 million (“Counting the Dead”, 2021) between December 2019 and May 2021 (roughly a year and a half).

Many of the conditions and capacities that sustainable development experts have been advocating for years – such as strong systems of governance and communication, safe and secure employment and housing, regionally efficient and functionally sufficient supply chains and distribution systems, and adequate public open space for outdoor gathering, recreation and exercise, psychological restoration, and urban environmental function – are the very investments that would have helped to limit the spread of this dangerous disease and ameliorate its effects. These imperatives of equitable development have gained a higher level of acceptability, thanks to the threat of widespread economic devastation and loss of life that are hallmarks of a global health crisis.

WHAT: infrastructures

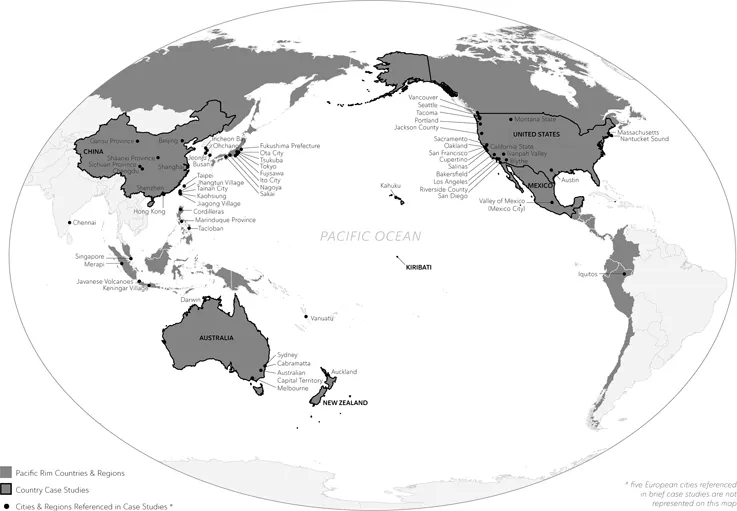

Systems are the basis of sustainable cities and landscapes. These include built systems, such as those for water conveyance and treatment, and for mobility of people and goods; socio-technical systems such as networks of communication and governance; and natural and landscape systems that support the environmental function and social needs of urban-rural regions. Taken together, such systems of interconnected space, energy, and activity organize the health of communities throughout the Pacific Rim and are the infrastructure of sustainable urban development. The role of infrastructure in regional and urban studies (Glass et al., 2019), in national and international policy contexts (Graham & Marvin, 2001), and in the lived experience of people moving through their daily lives (Amin, 2014) will understandably tend to focus on the large-scale, public works projects of ports, railways, power plants, highways, airports, sewers, bridges… the essential architecture of urbanization and industrialization (Gandy, 2014; Kaika, 2005; Schindler & Kanai, 2019). A unifying research interest of contributors to this volume is spatial; the infrastructures at the fore of our inquiries and analysis are physical and environmental, constructed or natural. The limited...