Panarchy Synopsis

Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Panarchy Synopsis

Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems

About This Book

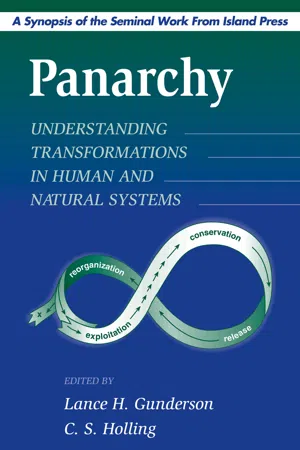

'Panarchy' is a new term coined from the name of the Greek god Pan, a symbol of universal nature and associated with unpredictable change. It represents an alternative framework for managing the issues that emerge from the interaction between people and nature. That interaction generates countless surprises, often the result of slow changes that can accumulate and unexpectedly flip an ecosystem or an economy into a qualitatively different state. That state may be not only impoverished, but also effectively irreversible. Thus, understanding how such change occurs is critical to achieving a sustainable society. Developed from the work of the Resilience Alliance, a worldwide group of leading organizations and individuals involved in ecological and economic research, Panarchy provides a framework to understand the cycles of change in complex systems and to gauge if, when, and how they can be influenced. This synopsis introduces lay readers and decision makers to this widely acclaimed line of inquiry and to the basic concept behind Panarchy, published by Island Press.

Frequently asked questions

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE ADAPTIVE CYCLE: SURPRISE AND RENEWAL

Four Phases of the Adaptive Cycle

- The rapid growth or r phase. Early in the cycle, the system is engaged in a period of rapid growth, as species or other actors colonize recently disturbed areas. These species (referred to as r-strategists in ecosystems), utilize disorganized resources to exploit every possible ecological niche. The system’s components are weakly interconnected and its internal state is weakly regulated. In ecosystems, the most successful r-strategists are able to proliferate despite environmental variation and tend to operate across small geographical areas and over short time scales. In economic systems, r-strategists are the innovators and entrepreneurs who seize upon opportunity. They are start-ups and producers of new products; they capture shares in newly opened markets and initiate intense commercial activity.

- The conservation or K phase. Transition to the K phase proceeds incrementally. During this phase, energy and materials slowly accumulate. Connections between the actors increase. The competitive edge shifts from species that adapt well to external variability and uncertainty to those that reduce its impact through their own mutually reinforcing relationships. These “K-strategists” operate across larger spatial scales and over longer time periods. As the system’s components gradually become more strongly interconnected, its internal state becomes more strongly regulated. New entrants are edged out while capital and potential grows, and the future seems ever more certain and determined. In an ecosystem, the potential that accumulates is stored in resources such as nutrients and biomass. An economic system’s potential can take the form of managerial and marketing skills, accumulated knowledge, and inventions.But the growth rate slows as connectedness increases to the point of rigidity and resilience declines. The cost of efficiency is a loss in flexibility. Increasing dependence on existing structures and processes renders the system vulnerable to any disturbance that can release its tightly knit capital. Such a system is increasingly stable, but over a decreasing range of conditions. The transition from the conservation to the release phase can happen in a heartbeat.

- The release or omega (Ω) phase. A disturbance that exceeds the system’s resilience breaks apart its web of reinforcing interactions. In an abrupt turnabout, the material and energy accumulated during the conservation phase is released. Resources that were tightly bound are transformed or destroyed as connections break and regulatory controls weaken. The destruction continues until the disturbance exhausts itself. The disturbance can occur when a slow variable triggers a fast variable response. For instance, the slow growth and aging of a fir forest triggers the outbreak of an insect pest. Or the slow growth of debt and gradual decline of profits finally triggers a financial panic.In ecosystems, agents such as forest fires, drought, insect pests, and disease cause the release of accumulations of biomass and nutrients. In the economy, a new technology can derail an entrenched industry. But the destruction that ensues has a creative element. This was Schumpeter’s “creative destruction.” Tightly bound capital—whether equipment, money, skills, or knowledge—is released and becomes a potential source of renewal.

- The renewal or alpha (α) phase. Following a disturbance, uncertainty rules. Feeble internal controls allow a system to easily lose or gain resources, but it also allows novelty to appear. Small, chance events have the opportunity to powerfully shape the future. Invention, experimentation, and re-assortment are the rule. In ecosystems, pioneer species may appear from previously suppressed vegetation; seeds germinate; non-native plants can invade and dominate the system. Novel combinations of species can generate new possibilities that are tested later.In an economic or social system, powerful new groups may appear and seize control of an organization. A handful of entrepreneurs can meet and turn a novel idea into action. Skills, experience, and expertise lost by individual firms may coalesce around new opportunities. Novelty arises in the form of new inventions, creative ideas, and people.Early in the renewal phase, the future is up for grabs. This phase of the cycle may lead to a simple repetition of the previous cycle, or the initiation of a novel new pattern of accumulation, or the precipitation of a collapse into a degraded state.Taken as a whole, the adaptive cycle has two opposing stages. The “front loop” encompasses rapid growth and conservation, and the “back loop” encompasses release and reorganization. The front loop is characterized by the slow accumulation of capital and potential, by stability and conservation. The back loop is characterized by uncertainty, novelty, and experimentation. The back loop, and the renewal phase in particular, is the time of greatest potential for the initiation of either destructive or creative change in the system. It is the time when human actions—intentional and thoughtful or spontaneous and reckless—can have the biggest impact.

An Industrial Cycle

Table of contents

- About Island Press

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION: - WHY PANARCHY?

- CHAPTER 1 - THE ADAPTIVE CYCLE: SURPRISE AND RENEWAL

- CHAPTER 2 - THE PATHOLOGY OF RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

- CHAPTER 3 - RESILIENCE

- CHAPTER 4 - CONNECTEDNESS

- CHAPTER 5 - MATTERS OF SCALE

- CHAPTER 6 - NATURAL CONGREGATIONS

- CHAPTER 7 - CASCADING CHANGE

- CHAPTER 8 - REMEMBER

- CHAPTER 9 - THE ADAPTIVE CYCLE AND LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

- CHAPTER 10 - HOW DO HUMAN AND NATURAL SYSTEMS DIFFER?

- CHAPTER 11 - CHALLENGES OF ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

- CHAPTER 12 - PANARCHY AND THE ECONOMICS OF NATURAL RESOURCES

- CHAPTER 13 - LEARNING: AN END AND A BEGINNING

- NOTES