- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

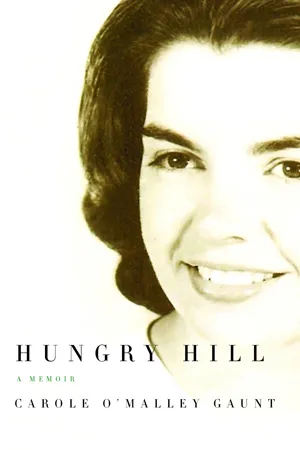

On a sweltering June night in 1959, Betty O'Malley died from lymphatic cancer, leaving behind an alcoholic husband and eight shell-shocked children—seven sons and one daughter, ranging in age from two to fifteen years. The daughter, Carole, was thirteen at the time. In this poignant memoir, she recalls in vivid detail the chaotic course of her family life over the next four years.

The setting for the story is Hungry Hill, an Irish-Catholic working-class neighborhood in Springfield , Massachusetts . The author recounts her sad and turbulent story with remarkable clarity, humor, and insight, punctuating the narrative with occasional fictional scenes that allow the adult Carole to comment on her teenage experiences and to probe the impact of her mother's death and her father's alcoholism.

The setting for the story is Hungry Hill, an Irish-Catholic working-class neighborhood in Springfield , Massachusetts . The author recounts her sad and turbulent story with remarkable clarity, humor, and insight, punctuating the narrative with occasional fictional scenes that allow the adult Carole to comment on her teenage experiences and to probe the impact of her mother's death and her father's alcoholism.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9781613762462Subtopic

Social Science Biographies1. Last Rites

LATER THAT SUMMER, I would resent that my older brother, Michael, knew all along my mother was dying. He had been told back in March, and I had not. I knew she was really sick. But as a thirteen-year-old, I believed in the magical power of miracles, believed in what the starched Sisters of Saint Joseph had told me: that a true miracle could occur at any time, if only I prayed hard enough. Either the nuns had lied to me, or I prayed the wrong prayers.

“Carole, I’m taking all the boys to Dombrowsky’s to pick up cold cuts. Then I’ll swing by the A&P to load up on groceries. I want the house quiet,” my father says in a low voice, staring at his clenched hands. Ever since my mother came home from the hospital back in May, the week after Mother’s Day, I have tried to keep the house quiet, even tomblike, ordering my brothers to play outside, day and night, in sun and pouring rain. My father’s starting to treat me as an equal, as if he knows he can always depend on me. He pops two Alka-Seltzers into a jelly glass, and I wait for the familiar fizz and watch for the explosion of tiny bubbles.

“Rose should be here soon, kiddo, so hold the fort,” he jokes, wiping white foam from his upper lip. At the door, nicked and scratched by the comings and goings of all my brothers, he hesitates. “The priest may come. Do whatever he asks. I’ll be back before the, the … Well, I’ll be back,” he says, leaving the door open behind him. When I walk over to close the door, I see my seven brothers packed into the 1958 Ford station wagon on a Saturday morning outing to the family butcher, and for half a second I wish that I were with them too, arguing and bickering and lobbying for the shotgun position. Yet I do like the responsibility, being singled out, the specialness of being in charge.

I pry a Hydrox cookie perfectly apart to glide my teeth over the sugary white filling and wonder whether my father said he had called the priest? Is that what he said? No, that’s not what he said. He said the priest was coming. So did that mean the priest had called him? Why hadn’t I asked my father? Because he wouldn’t have answered me anyway? Besides, I already knew that the priest was coming to see my mother. Extreme Unction. Last Rites. Hocus-Pocus. I am licking crumbs of chocolate from my fingers when I hear a slight moan from my parents’ bedroom, a moan I decide to ignore. On Wednesday night, my mother slipped into a coma, but she would slide in moans at the odd moment. Rose, the nurse, should be here any minute and she will know what to do. My mother, I think in some tiny scrap of my brain, may be dying.

When the front doorbell rings, my mind starts jumping, “No one’s here. I’m all alone. Where is Rose? What’s happened to her?” I know it’s the parish priest because Rose would have come straight in the kitchen door. Anyone but the pastor, Father Power, I think as I hurry into the living room. I feel perspiration pooling under my arms, so I pull at my blouse. With a lurch, I open the living room door, scraping it over the carpet, and Father Miller, somber-faced, missal in his hand, is standing on the front porch. At church, Father Miller’s sermons win for most boring—he never even tries to tell a joke in the first few minutes. I hope nosy Jay Vecchiarelli isn’t watching from behind a shade across the street. I so want to hurry Father Miller in, but I hesitate, wordless, until after a moment he asks, “Where is your mother?”

As I lead him to the sickroom, my mother and father’s bedroom, Father Miller asks me whether anyone else is home. Mechanically, he goes to the left side of the blond bookcase bed. Behind him, the drawn slats of the green venetian blind look like stripes neatly overlapping. As he studies my mother, whose pale, damp skin has a saint-like look, I shift from foot to foot. Although the sickness has made her, always a pretty woman, now ethereally beautiful, I can’t make myself look at her. It’s just too hard. With a confused expression on his face, Father Miller clears his throat and says, “You can’t do this alone, Carole. We’ll need someone else, another adult, since your father’s not here.” His words carry a pinprick of accusation—that I can’t handle it—whatever it is.

“Rose, she’s the nurse, well, really she’s my uncle’s sister, should be here any minute. My father told me that when he left,” I explain, watching Father Miller set his prayer book on the end table.

“Is there a neighbor, anyone next door? Someone who could come over to be here?” he persists in the same monotone he uses in his Sunday sermons. Then, placing a purple stole around his neck, he directs me: “I want you to go next door to see if there is anyone there who could come over, Carole.”

I stare at the speckled linoleum as I cross the kitchen floor wondering why I have to go get Mrs. Metzger to come over when my father didn’t say anything about it. “I’m letting my dad down,” I think as I cut through the opening in the hedges. I glance at the tar-cracked driveway and notice the deep scars winter has etched in its once smooth surface. I knock twice on the Metzgers’ door and wait, secretly hoping no one is home. Dressed in a faded chenille robe, Mrs. Metzger scuffles to the door, her blond hair a smooth pith helmet.

“Yes, Carole, what is it?” she asks with a small smile.

“Father Miller’s at the house for my mother and he wants you to come over, if you can,” I say, the words rushing out while I point to Father Miller’s black Chevrolet parked in front of the house.

“Just let me change. I’ll only be a minute. Come in, come in. Wait here, Carole,” she says, quickly disappearing down the hall. Mrs. Metzger bakes three days a week, and there is a fluted apple pie on a metal rack cooling on the counter. I breathe in the sugar-cinnamon smell of this kitchen, yet know from playing with the Metzger kids in the backyard that Mrs. Metzger has a vicious temper so I cannot be lulled into letting my guard down. In no time, Mrs. Metzger stands in the hallway in a beige wrap skirt with a matching blouse that she is still tucking in. As I follow her up the three back porch steps to my house, I study the tiny, even stitches in her skirt trying to figure out whether she has sewn this outfit or whether it’s store-bought.

When we enter the sickroom, Father Miller nods slowly to Mrs. Metzger, and I keep my eyes on the hunter green goose-necked reading lamp attached to the blond bookcase bed, as if I have never seen it. My dad’s Time magazine is spread open, and I move to close it when Father Miller’s cough startles me.

“Carole, we’re ready to begin. You stand next to Mrs. Metzger there at the foot of the bed,” he directs in a soft confessional voice. Mrs. Metzger stands barely a foot from me, much too close. I begin playing with the gray line under my fingernails. Raising his eyebrows, Father Miller indicates he is satisfied with our bedside positions, and he begins reading solemnly from his black prayer book. I am trying to make out the gold lettering through his fingers when there is the tinny sound of the aluminum door closing. Rose’s heels click across the kitchen floor, and in a minute she rushes into the bedroom, all out of breath.

“I’m so sorry. Jimmy needed a ride to his Little League game and Monty had to work. Hello, Father, I’m Rose Montanari from Holy Name parish,” Rose says, slowing her voice as she talks to the priest. Masking his impatience, Father Miller mumbles that we will start again. Rose straightens the bed sheet and feels for my mother’s hand. Reaching down, she places her handbag under the night table as if this was the signal for Father Miller to begin.

Father Miller recites the prayers in English as well as in Latin, but everything is a foreign language to me. I am tuning out, trying to envision the magical power of a miracle, wondering if a miracle has ever occurred in Springfield, Massachusetts. Now, the priest anoints my mother’s high, unlined forehead with oil. So this is anointing, I think, wrapping one leg spaghetti-like around the other to test my balance and, half-smiling, I picture myself toppling to the floor. Father Miller moves his lips in prayer and asks us to make a response. If I have to talk, I might cry. A panic hits me because I have no idea what it is Mrs. Metzger, Rose, and I are supposed to repeat after him. Dustballs seem to climb up the sides of my throat. “I’ll let them do it. I’ll just move my lips. Maybe I’ll mumble,” I think.

Through the window, I can hear Jay and Joe Vecchiarelli yelling at each other outside on the street, fighting over a turn at bat. Father Miller winces, his link with divinity jarred, at the cracking noise of a bat hitting a baseball. In here, a heavy, slow-moving quiet spreads throughout the room. Suddenly, a miracle.

“Take care of my baby, take care of my baby, Tommy! Who will take care of my baby?” My mother lifts her head from the pillow, opens her eyes, sits bolt upright in bed with her arms extended heavenward, and, in a yelling-in-the-schoolyard voice, begs for my baby brother. Miracle or not, I hear myself screaming. Rose places her big hand on my mother’s bony wrist and assures her firmly that they will take care of the baby, not to worry. I feel strong arms pinned around me and hear Mrs. Metzger’s steady voice in my ear, saying, “Carole, Carole, there, there.” My screaming fit ends, and I shake off her capable arms. Father Miller wipes some spit gathering in the corner of his mouth. My stomach flip-flops but, looking at my mother for the first time that day, I tell her, “I’ll take care of the baby, Mom. I will, I promise.” In a split second, she’s gone again, lost. As mysteriously as the ghostlike flash of consciousness came in her, it disappears and her head falls back onto the pillow. Is this the miracle?

Tommy’s barely two. What have I promised? Does my mother even know that I’m here? Funny, how my mom didn’t say anything about my dad, mention his name, or me, standing right there. Then, needing a way for me to get through Father Miller’s mumbo jumbo, needing the forms, the rite to end, I am imagining myself outside on the street running bases with Jay and Joe Vecchiarelli when Father Miller folds his purple stole, walks over to me, and extends his hands. Am I supposed to kiss his ring like Bishop Weldon’s at Confirmation? Is he wearing a ring? He grips my sweaty palms and pats my shoulder, and I can see tears welling in the corners of his eyes. Priests can’t cry. Please, Father, don’t cry.

Rose begins lining up the medicines in alphabetical order and by volume on the night table. Mrs. Metzger pushes me toward the door, and I follow Father Miller down to the kitchen hallway.

“Tell your father that I was here, and that she can go to the hospital anytime now,” Father Miller says to me in an almost kind way.

I am relieved to have directions to follow. But the next moment, barely breathing, I ask awkwardly:

“Father, in sixth-grade religion, Sister said that sometimes miracles occur when the Last Rites are given? Have you ever seen any miracles?” Can I go to hell for this? Asking the priest a question?

“Your sixth-grade teacher was Sister Mary Matthias?” Father says to me as I study the black dots of whiskers on his sunken cheeks.

“Yes, Father.”

“I’ll have to talk to Sister,” he says, placing his hand on the kitchen doorknob. At that instant, Father Miller and I both know that there will be no more miracles. Maybe God knew that, despite my prayers and the good grades and the perfect conduct mark, it was all an act. Still, the rebel streak in me won’t let me stop hoping.

Father Miller and Mrs. Metzger are outside at the edge of the driveway, their arms folded, their eyes on the house. For a minute, I stand there and then scrape specks of white paint from the brass doorknob with my fingernail until Father Miller drives off.

The sun is blazing down on the driveway with shiny bubbles of tar forcing themselves through the surface when our station wagon rounds the corner. My brothers pile out, slamming doors. My father implores them to be quiet, to stay out of the house until lunchtime, to think of “your sick mother.”

My dad’s carrying three brown bags brimming with groceries and shoves his broad shoulder against the door so that he can drop them on the kitchen table. I take the gallon of milk from his hand. His cheeks look red to me, and I think maybe it’s the heat until I smell the whiskey on his breath.

“Hey, Princess, what’s up, kid?” my dad asks, putting the neatly wrapped packages of meat into the freezer.

“He came,” I say, pulling out a box of Rice Krispies.

“Who came?” my dad asks and hoists the milk into the refrigerator.

“Father Miller.”

“Oh, he did?” My dad pauses with a quart of boysenberry ice cream, his favorite, in his hand.

“Yeah, I got Mrs. Metzger to come over. He made me get her.”

“Well, that’s good,” he says, as if he didn’t hear me and turns his back to open the freezer.

“He said to tell you Mom could go to the hospital anytime now. Dad, is she going?” Just this once, I want him to answer me, to be honest with me.

“I don’t know, Carole.” He knows, but he’s not telling me.

“Di and Anne are waiting for me at Van Horn,” I tell him. My brothers and I come and go as we please, never needing to ask permission.

“Shoot a little hoop with your friends?” he asks.

I shrug and say, “Rose is in there, with Mom.” I show off some basketball tricks for him, pretend I’m dribbling, feint, and hang a hook shot. My dad smiles, and I jump down the porch stairs three at a time.

On my way to Van Horn Park, I picture myself a frenzy on the basketball court, making lay-ups, hook shots, jump shots, foul shots, shots from midcourt, and suddenly I’m shivering, with goosebumps popping up on my arms, as I realize how my dad had left me all alone.

Later, when I would try to figure out how our lives went so wrong, I marked my mother’s death as the beginning of the end.

MOTHER’S DAY 1992

Joe O’Malley, Carole’s father, looks around her apartment. He appraises the furniture, the draperies, and nods his head in a gesture of approval. Adjusting the sofa pillow behind him, he leans back and plants his feet.

JOE: Hey, Katsy, I wish your mother could see this apartment. God must be smiling at you these days.

CAROLE: You could say God’s not so distracted these days. Do you still take milk and sugar in your tea?

JOE: I guess you’re not offering me anything stronger. I’ll have to settle for this weak sister tea.

CAROLE: Weak sister? Why not weak brother? Dad, that expression sounds to me like you’re putting down women.

JOE: (Placatingly.) I’m sorry, Punkin. You seem defensive.

CAROLE: You’re familiar with the word “sexist”?

JOE: (Half jokingly.) There was no women’s movement in my day. (His exp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: Limelight

- 1 Last Rites

- Mother’s Day 1992

- 2 Gone

- 3 God Takes the Saints Early

- 4 Chocolate Cake

- 5 Perfect Skin

- 6 Anne of Green Gables

- 7 Graduation Dress

- 8 Honor and Privilege

- 9 Complete Change of Scene

- 10 Kelsey Point

- 11 The Boys at the Corner Drugstore

- 12 My Mother’s Closet

- Saint Michael’s Cemetery

- 13 The Boys’ Bathing Suits Are Missing

- 14 An Evening of Informal Modeling

- 15 The Jewel of the Diocese

- 16 The Dark Horse

- 17 Campaign

- 18 The Dating Scene

- 19 Cheerleading and Candy Striping

- 20 Clip-on Tie

- 21 Auxilium Latinum

- 22 A Buyer of Sofas

- Mother’s Day 1993

- 23 The Doctor’s Revelation

- 24 Casanova at the Beach

- 25 Stage, Left, Stage Right, Entrances and Exits

- Armistice Day 1994

- 26 Party Time

- 27 Joey, the Bird

- 28 Fledgling Journalist and Mad Scientist

- 29 Under the Knife

- 30 Dress-up Day

- 31 Sweet and Sour Times: Easter, the Election and (Step)Mother’s Day

- 32 Fifteen Forever

- 33 The Ambush

- 34 Planning for the Future

- 35 Lil’ Kiss

- 36 Skidding

- 37 Snowbound

- 38 Down the Drain

- 39 Hold the Fort

- 40 Imperfect Prayers

- 41 A Yellowed Cheek

- 42 Cashmere Sport Coat

- 43 Dr. Blackmer’s Magic

- 44 Job Market

- 45 Bargain Tables

- 46 Beautiful

- 47 A Ten-Second Phone Call

- 48 Rich Woman Someday

- 49 Handbag

- 50 Best Tunafish

- Scotch and Soda—A Transcription

- 51 Only a Dish

- 52 Term Projects

- 53 Runaway

- 54 Prom Fever

- The Nuclear Option

- 55 We’ll Remember Always Graduation Day

- Epilogue: Fade Out

- Acknowledgments

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hungry Hill by Carole O'Malley Gaunt in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.