![]()

1

Green Stormwater Infrastructure on Vacant Lots

The benefits that urban green space provides to cities have been well documented. It reduces expenditures for vital services such as air filtration, stormwater management, and temperature regulation.1 Urban green space adds value to nearby properties, increases commerce, and reduces violent crime. It improves human health outcomes2 by reducing stress,3 encouraging exercise,4 and reducing illness and death from respiratory disease. The Vacant to Vibrant project was inspired to bring these benefits to areas where they could assist with neighborhood stabilization. We created a project to build urban green space on small vacant parcels in three post-industrial cities with the goal of improving the environmental and social fabric of neighborhoods.

Vacant to Vibrant began as a hashtag, #vacant2vibrant, used to organize conversations over a series of interdisciplinary meetings in 2009 and 2010.5 Dozens of professionals from city government, sewer/stormwater authorities, and urban greening organizations from 11 Great Lakes cities met to characterize shared problems that were emerging as state and federal monies were being invested in blight removal and demolition of abandoned buildings, creating growing catalogs of vacant lots. We wanted to understand existing vacant land reuse efforts and explore how these might complement environmental initiatives that were taking place in the same cities.

From this process, the group identified three areas of need that were common to many urban areas in the Great Lakes region:

- Large quantities of vacant land that were unproductive and expensive to maintain

- Outdated sewer systems that were creating a need for better stormwater management in the face of a changing climate

- Neighborhoods that had weathered the environmental and social effects of decades of industrial decline

Vacant to Vibrant drew upon innovative vacant land reuse work that had been undertaken in many places around the US, such as pocket parks, green stormwater infrastructure, urban farming, and “clean-and-green” neighborhood stabilization projects. While its primary focus was finding a way to use vacant lots to benefit the Great Lakes ecosystem, Vacant to Vibrant differed from many environmental projects that were being implemented at the time in its equal emphasis on the social and the environmental needs of urban neighborhoods. Its effort to combine vacant land reuse, green stormwater infrastructure, and neighborhood revitalization tested whether land use strategies could be stacked within the small footprint of a single lot.

The project included beautification of three vacant parcels in one neighborhood in each of three Great Lakes cities—Gary, Indiana; Cleveland, Ohio; and Buffalo, New York. We targeted declining neighborhoods that could benefit from stabilization and set out to develop modest urban greening approaches that were customized to the needs of those neighborhoods. Rain gardens were added to each parcel, as well as landscaping or equipment that supported a recreational use for residents. The type of recreation varied from very passive, such as walking, bird-watching, or picnicking, to more active, such as handball or active play. Where possible, flower beds and low-maintenance plants replaced lawn to reduce mowing requirements and add habitat. In the interest of replicability, we strived for modest projects with installation costs ranging from $7,000 to $35,000 (average: $18,000) over nine installations.

This approach contrasted with large stormwater management projects that were being undertaken in Milwaukee, Chicago, and Cleveland on aggregated vacant land. It also contrasted with green streets and smaller stormwater management projects that were being constructed in stable or gentrifying neighborhoods in many cities throughout the US. Beyond the construction of projects themselves, Vacant to Vibrant was an attempt to document processes and lessons that could help lead to systemic change—change that would be necessary if cities want to grow green stormwater control up to the level of “infrastructure.” The three cities provided separate examples of how manufacturing cities are grappling with adapting old systems to new, green technology.

In this chapter, we explore how population loss that created thousands of acres of vacant land also contributed to letting underlying urban infrastructure fall out of date. As a result, cities with a shrinking base of tax- and ratepayers are contending with large sewer infrastructure updates for regulatory compliance. Examining these two problems in tandem may suggest where and what form joint solutions might take to repurpose vacant lots for the benefit of environmental quality.

Excess Urban Vacant Land

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, US cities boomed with the spread of industrialization. Near the Great Lakes, where expansive bodies of freshwater fueled production and provided access to international shipping routes, cities rapidly expanded under steel and manufacturing. Large cities annexed smaller towns and undeveloped land to support an influx of residents from the East, rural areas, and abroad. They laid roads, sewers, and other infrastructure in an expanding urban grid. When rivers and beaches blackened and caught fire, their loss was a cost of progress.

After the demands of World War II ended and manufacturing slowed in the region, city economies began shifting away from heavy industry. On the Canadian side, early economic diversification to embrace light industry, tech, and service sectors spurred population growth in the 1970s that continues to this day.6 A short drive across the border into Detroit or Buffalo, however, shows that Great Lakes cities on the US side did not adapt as quickly. Job loss caused by automation and imports was exacerbated by US racial politics. Desegregation of schools and neighborhoods fed white flight and urban sprawl that gutted downtowns and permanently altered the demographics of urban neighborhoods.

Many American post-industrial cities continued to lose population from the 1960s onward. In some cities, the pattern of population loss was widespread across most of their land area (Detroit, Gary, Flint). In other places, population loss and disinvestment were concentrated in some neighborhoods, while other areas continued to grow (Chicago, Philadelphia, New York). In the 1990s, it was common to see a distribution of regional population in a doughnut shape around cities, with thriving suburban areas surrounding decaying urban cores.7 Today, as population loss slows, cities are receiving an influx of younger, highly educated residents, so that downtown growth and continued suburban development now sandwich decaying urban neighborhoods. In development hot spots, problems of urban decay are now being replaced with problems of gentrification. Today, rather than thinking of urban shrinkage as a permanent phenomenon, it is thought that shrinkage is one phase of the urban life cycle that precedes growth.8

Cities positioned near the Great Lakes have been particularly affected by vacancy due to regional industrial decline since the 1970s, with 14 of the 20 largest cities experiencing population loss of 15 to 45 percent over 40 years.9 How this population loss scales with the quantity of vacant land depends on cities’ capacity to undertake large-scale demolition efforts—some cities have had more access to resources for demolition than others. Vacant land is not unique to cities that have gone through decades of depopulation, however. Land vacancy exists in a majority of cities throughout the US,10 such as cities that have gone through rapid expansion, or cities where geography or policy has allowed sprawl to go unchecked. Aside from house demolition, other conditions that create vacant land include soil contamination, undevelopable slopes, and oddly shaped parcels left by highways and urban sprawl. Finding productive ways to reuse vacant land is of interest to a variety of countries in Europe and Asia, where slower population and economic growth rates, deindustrialization, suburbanization, and globalization have contributed to population loss in cities. As in parts of the US, these conditions abroad have created urban areas that are contending with environmental quality problems, outdated infrastructure, and land vacancy.11

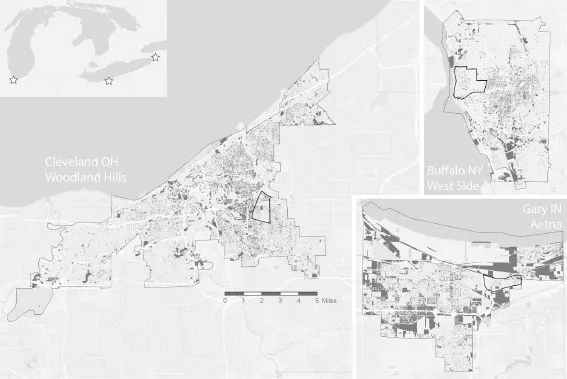

Development of small residential parcels during periods of growth, followed by widespread property abandonment, foreclosure, and demolition of vacant structures during industrial decline, has resulted in hundreds or thousands of vacant parcels per city in the Midwest and northeast regions (figure 1-112). Vacancy can occur as large parcels that often bear the contamination of past industrial use, but urban vacant land more commonly takes the form of small residential or commercial parcels that dot street corners and are sandwiched between homes. Due to the piecemeal nature of abandonment and demolition, vacant lots are usually unconnected from one another except in neighborhoods that have had very high rates of population loss (for example, in Cleveland, 85 percent of vacant land exists as three or fewer contiguous parcels, and more than 96 percent of vacant land aggregates are smaller than 0.2 hectares in size). The separation of vacant lots in space and in time—in addition to varied land use histories, sheer number, and the limited resources of shrinking cities—have made it difficult to put vacant lots into productive use.

With population and/or economic stability returning to manufacturing cities, planning for growth has taken on a tone of increased urgency and realism. Smaller, single-company manufacturing cities, such as Flint, Michigan, and Youngstown, Ohio, are planning to shrink urban infrastructure to match projections that population will remain smaller in the long run. Most larger cities shy away from shrinkage as an overt strategy, however, viewing it as being unflattering or pessimistic. These cities are cautiously envisioning what vibrant futures might look like.

In particular, shrinking cities that are situated near abundant freshwater are poised for future growth. There is renewed interest in restoring the rivers and lakes that once made eastern cities attractive to manufacturing, while water scarcity predictions for the Southwest and western US have underscored the potential of abundant clean water for future economic growth. These cities are rediscovering clean water as an asset. On shore, nostalgia for earlier times has also rekindled a longing to reclaim “forest cities,” a nickname that several cities in North America (Cleveland, Ohio; Rockford, Illinois; London, Ontario, Canada; Portland, Maine; and Middletown, Connecticut) once shared. Environmental compliance issues and climate uncertainty are spurring planning that views water and trees through the lens of climate resilience.

Figure 1-1. Like many post-industrial cities that have had significant population loss over the past several decades, the three Vacant to Vibrant cities in this book—Cleveland, Ohio; Buffalo, New York; and Gary, Indiana—have an abundance of urban vacant land. Data sources: NEOCANDO and City of Cleveland, Cities of Buffalo and Gary, Esri.

Although13 generally considered “blight,” high rates of urban land vacancy in US post-industrial cities present an opportunity for new, climate-smart patterns of urban redevelopment. On the flip side of manufacturing loss is an opportunity for post-industrial cities to reinvent themselves as vibrant urban areas, where clean, green space serves the economy, residents, and the environment.

Vacant Land as Urban Green Space

In this time of abundant vacant land, “legacy” cities have a window of opportunity to shift away from previous patterns of development by intentionally planning for vacant parcels that will not be rebuilt. Instead, they can re-create themselves as greener cities that are more resilient to future threats by planning for urban green space that is more densely and equitably distributed. By learning from cities that have grown too quickly or densely, they can avoid future costs and problems associated with trying to retrofit green space into densely populated areas.

Managing vacant parcels is often seen as a temporary problem—when there is demand for property for tax-generating land uses again, planners will no longer be asking what vacant parcels are good for. The larger point of vacant land management goes beyond finding interim uses for parcels until they can be redeveloped; it extends to helping determine the best long-term use for parcels within a vibrant city from among a wide array of possibilities. This includes developing criteria for how parcels should be redeveloped or whether they should be redeveloped at all. By describing the full suite of benefits that urban green space provides, including ecological and social benefits, and the monetary value of those benefits, urban greening practitioners can incorporate informed decision making into the planning process for redevelopment. Good policy will be crucial to ensure that adequate green space is preserved for neighborhoods as parcels are acquired and developed one at a time, all over the city, across decades.

While green infrastructure has been embraced in regions such as the Pacific Northwest, manufacturing cities tend to prefer the certainty of traditional engineering solutions. Extensive greening in the urban core also conflicts with the original development patterns of these cities—modest houses in densely packed neighborhoods that did not contain much urban green space. However, abundant vacant land resources and philanthropic interest in green jobs are pushing blue-collar urban areas to explore the potential in green infrastructure.

The Slavic Village neighborhood in Cleveland is a good illustration of development patterns that persisted in industrial cities into the 1950s. Narrow 40- by 100-foot parcels were built up into two- and three-story colonial houses that stretched from driveway to driveway. Detached garages, and sometimes another small house to hold family from the old country (the “mother-in-law suite”), filled the rear of the parcel. Most trees were cleared. Today approximately one-quarter of the parcels in Slavic Village are vacant, and many houses have been abandoned and condemned, awaiting conversion to vacant land through demolition.

Yet many city officials and residents, in Cleveland and elsewhere, still cling to midcentury images of crowded parcels, filled with impervious surfaces that we now know contribute to sewer flash floods that lead to overflows, as a badge of their cities’ heyday. Even with clear evidence that modern development patterns should change, they continue to assume that their cities will again be healthy when every parcel is built back up to its original glory.

This idea may not be stated explicitly but can be perceived between the lines in plans that fail to preserve some vacant parcels as permanent urban green space. Many cities largely lack regulations that force the preservation or creation of urban green space, particularly in densely packed or quickly growing neighborhoods, despite a current window of opportunity to envision neighborhoods that are more equitable, walkable, and climate resilient. Many of these same cities do promote green reuse of vacant lots as a temporary holding strategy, however, and p...