![]()

1

The Stages of Memory at Ground Zero

The National 9/11 Memorial Process

On September 11, 2011, ten years to the day after two planes were flown by terrorists into the World Trade Center’s twin towers in Lower Manhattan, a bell tolled at the site of the attacks, and President Barack Obama dedicated the opening of the National September 11 Memorial. On that morning, with skies as “severe-clear” as they were on that day in 2001, invited attendees included the family members of the 2,982 victims of the attacks in New York City, at the Pentagon, and on the terrorist-commandeered United Airlines Flight 93 that crashed near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, as well as of victims of the February 26, 1993, World Trade Center bombing. Together with the President and Mrs. Obama, Secretary of State (and former New York senator) Hillary Clinton, Mayor Michael Bloomberg, and dozens of other national, city, and state officials and politicians, the family members entered the memorial plaza for the first time. They filed in somberly and quietly, their voices muffled by the soft roar of waterfalls along the edges of the towers’ footprints, 200 feet square and 35 feet deep, each pool with a further large void at its center.

Many of these family members and politicians had also attended the annual commemorative ceremonies at Ground Zero which had taken place every September 11 since the attacks, when bells tolled to mark the moment of the planes’ impacts and the moments when each of the towers collapsed. Every year, family members would read their lost loved ones’ names one by one, and then carry long-stemmed roses down a long ramp to be cast upon two small, square reflecting pools set up at bedrock 70 feet below street grade. The ten-year interval between the 9/11 attacks and the dedication of “Reflecting Absence,” the memorial designed by Michael Arad and Peter Walker, seemed perfectly respectful, even a little belated (the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was dedicated just eight years after the end of the war). But for the victims’ families, local neighbors, city officials, memorial and museum designers, and others involved in the rebuilding of Lower Manhattan, there seemed to be almost no interval at all between the attacks and the city’s memory of them, a memory they experienced in its long durée as a continuous (if exhausting) skein of simultaneous rebuilding and remembering. The dedication of the National September 11 Memorial was just the latest, but not the last, of many stages of memory at Ground Zero.

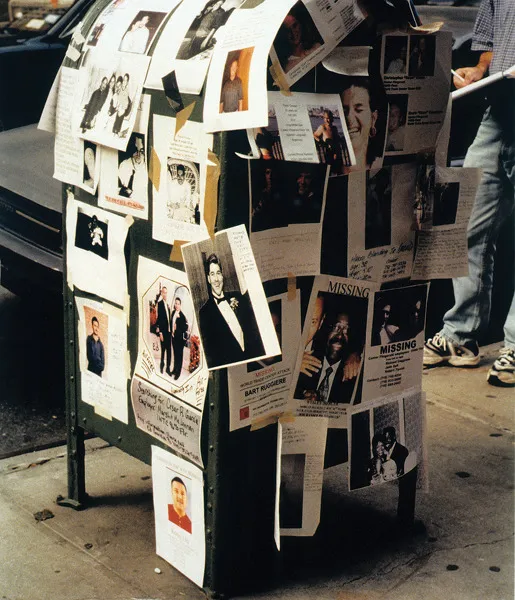

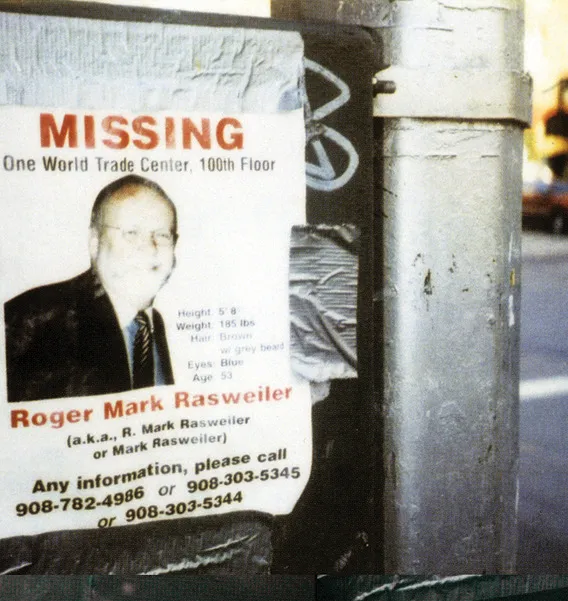

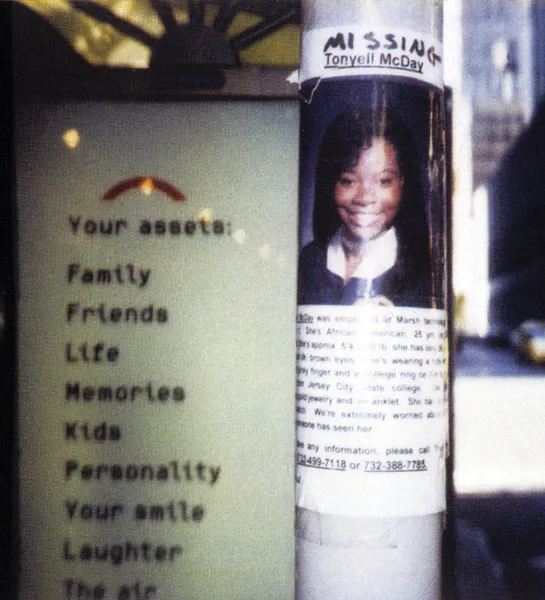

For the families of victims and residents of New York City, there was no immediate need to ask how these attacks would be memorialized, for as a process, “the 9/11 Memorial” was already there—in the candlelight vigils by hundreds of city dwellers in Union Square, Washington Square, and on the promenade in Brooklyn Heights the same evening of the attacks; in the votive candles placed in lobbies of apartment buildings throughout the city that mothers, fathers, and children didn’t come home to that evening; in the mountainous piles of flowers and wreaths laid in front of fire stations in every borough of the city; in the thousands of flyers of “missing” loved ones posted throughout the city for several days by families and friends of those who never came home. These photos and descriptions of loved ones were the spontaneous commemorations of loss and grief. Replete with images and descriptions of fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, these flyers read almost as epitaphs on paper instead of stone, as perishable and transitory as the hope that inspired them. These families’ missing loved ones were, in turn, remembered and mourned by all who came across these ephemeral, “found memorials.” Even without a conscious, systematic effort, a key memorial motif—absence—was thus spontaneously established by those who had begun mourning lost loved ones within hours of the falling towers.

On the two-month anniversary of the attacks, the New York Times Magazine ran a piece called “[Reimagine]; What to Build,” which asked “two architects, an urban planner, a structural engineer and a landscape designer [to] consider the future of ground zero.”1 All of the proposed designs included spaces for a memorial, and some of the designers suggested that the space itself was the memorial. In his proposal, “A Memorial in the Sky,” the landscape architect Ken Smith called for both a new skyscraper and a memorial on its roof, in the sky (composed of the faces on the flyers still posted around the city), where visitors would have to make their pilgrimage to join those who “disappeared into the sky.” In Smith’s words, “this is one way to think about it, to experience the emptiness, see all those faces and feel the loss” (96). Within two months of the 9/11 attacks, “rebuilding” had now joined “absence” as its twin memorial motif, a pairing continued throughout the memorial and redevelopment process, and which found expression in the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation’s triadic motto: “Remember, Rebuild, Renew.” Remembering, rebuilding, and renewing—each regarded as an extension of the other—would now constitute the very raison d’être of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, a joint state–city corporation formed by the governor and mayor to oversee the rebuilding and revitalization of Lower Manhattan.

![]()

![]()

For the next six months, further stages of memory included the ever-changing landscape of destruction at Ground Zero. Where the seven-story mountain of tangled and jutting ruins stood literally as remnant of the ferocity of the attack and mass death, the gigantic hole in the ground came to stand as literally for the immeasurable void left in the city’s lives and hearts, an open wound in the cityscape. The feverish pace of attempted rescue turned into a recovery operation, then into a salvage and cleanup process, bespeaking the need of all to remember this terrible breach by repairing it.

On March 11, 2002, the six-month anniversary of the attacks, the site installation of two stunning “towers of light” composed of eighty-eight seven-thousand-watt high-intensity xenon lights positioned to echo the original twin towers beamed four miles high into the sky above Lower Manhattan. Seeming to reach infinitely into the heavens and visible from a sixty-mile radius, Tribute in Light (as it was renamed in deference to the human victims of the attacks) struck the millions of people who saw it as the perfect balance between the monumentality of the towers and their ultimate ephemerality, now consoling memorial beacons to the victims of 9/11.

Originally conceived and designed in 1999 by artists Julian LaVerdiere and Paul Myoda as a single-column “light-sculpture” (titled Bioluminescent Beacon) for installation atop the 360-foot radio tower on World Trade Center Tower One as a celebratory installation for the Twin Towers’ thirtieth birthday in 2002, it was reconceived by the artists shortly after the attacks as two “phantom towers” of light for the cover of the September 23, 2001, issue of the New York Times Magazine.2 At just about the same time (and unbeknownst to the artists), two architects from Proun Space Studio, John Bennet and Gustavo Bonevardi, were developing a light installation they titled PRISM (Project to Restore Immediately the Skyline of Manhattan), which also called for twin rectilinear clusters of light to be beamed skyward from barges in the Hudson River near Battery Park City. Shortly after discovering each other, the artists and architects teamed up together with the lighting designers Paul Marantz and Jules Fisher. Jointly sponsored by Creative Time and the Municipal Art Society of New York, they developed what became Tribute in Light, shown to such great acclaim on the six-month anniversary that it would be installed again on every anniversary of the 9/11 attacks thereafter—an annual kindling of lights to remember the massive loss of lives and buildings on that day in 2001.

By the six-month anniversary of the attacks, at least a dozen public symposia, conferences, and print media forums had also been held throughout the city at academic, cultural, and community venues. Like many others who had previously written about memorials and consulted on them, I was invited almost weekly to weigh in on how to frame and think about what was then being called the World Trade Center Memorial. I replied as honestly as I could that I wasn’t sure where the unfolding history of the 9/11 attacks and their aftermath ended, and where their memory began. Beyond the immediate loss of nearly three thousand lives and the devastation of Lower Manhattan, I wasn’t even sure what the “meaning” of the attacks was, and without some kind of agreed-upon meaning, I wasn’t sure we could begin memorializing the events of that day. Only the loved ones and friends of victims had an absolute grasp on what their losses meant, what the attacks meant to them, and to the families and colleagues of firefighters and other first responders whose deaths were understood as both civic and personal tragedies.3

![]()

![]()

At each of these meetings, I ended up reprising some variation on all of these themes. As stages of mourning turned into stages of memory, I said, “the memorial” always needed to be regarded as a process, a continuum of stages. Before settling on a final plan for the new World Trade Center and a memorial to the 9/11 attacks, as urgent a task as that may have been, I believed from the outset that it might help first to articulate the stages of the memorial process itself—as a guide to where we’ve been, where we are, and where we would like to go. In so doing, we would begin to define a conceptual foundation for this site, which would take into account all that was lost and all that must now be regenerated. Here we needed to ask: What is to be remembered here, and how? For whom are we remembering? And to what social, political, religious, and communal ends?

Would this be a site commemorating the old World Trade Center and the thousands murdered here, or one that merely replaced what was lost in the attack? By necessity, it would be both. This is why we needed to design into this site the capacity for both remembrance and reconstruction, space for both memory of past destruction and for present life and its regeneration. This would have to be a complex, integrative design that meshes memory with life, embeds memory in life, and balances our need for memory with the present needs of the living. Our commemorations must not be allowed to disable life or take its place; rather, they must inspire life, regenerate it, and provide for it. We must animate and reinvigorate this site, not paralyze it, with memory. In this way, we might remember the victims by how they lived and not merely by how they died.

This is also why I argued strenuously that this devastated site should not be turned into a memorial only to the lives lost here. Such a memorial would preserve the sanctity of this space, as former mayor Rudolph Giuliani suggested at the time, but it also inadvertently would sanctify the culture of death and its veneration that inspired the killers themselves. For whether we like it or not, memorials to death and destruction can also monumentalize and privilege such death and destruction. Our memorial to the destruction of the towers and the lives lost also could even become the terrorists’ victory monument. Our soaring shrine to the victims and our sorrow could become the murderers’ triumphal fist, thrust into the air.

And what of the ruins? All cultures preserve bits of relics and ruins as reminders of the past; nearly all cultures remember terrible destructions with the remnants of such destruction. But Americans never have made ruins their home or allowed ruins to define—and thereby shape—their future. The power of ruins is undeniable, and while it may be fitting to preserve a shard or piece of the towers’ facade as a gesture to the moment of destruction, it would be a mistake to stop with such a gesture, and allow it alone to stand for all those rich and varied lives that were lost. For by itself, such a remnant (no matter how aesthetically pleasing) would recall—and thereby reduce—all this rich life to the terrible moment of destruction, just as the terrorists themselves would have us remember their victims.

For some New Yorkers, it was similarly tempting to leave the void itself behind as a permanent symbol of the breach in their lives, the emptiness they felt in their hearts. I know for many the physical void left behind was nearly unbearable, a constant reminder of life changed, of mass death nearby, a personal assault on their “home.” And sometimes, nothing seems to evoke such loss better than the gaping voi...