Box 1

Richmond, California: The Industrial City by the Bay

To fully understand the importance of a racial justice approach in Richmond, it is important to know a little about the city’s history. Richmond sits directly across the Bay from San Francisco, with over thirty miles of shoreline. After gold was discovered in California in 1849, thousands moved to the Bay Area, and the burgeoning ports and fertile soil in Oakland and Richmond became highly sought after land. By the end of the nineteenth century, Richmond was a strategic part of California’s (and the US’s) growing maritime industry. The Santa Fe Railroad made Richmond the terminus of its transcontinental railroad in 1899, where it connected to a ferry to transport passengers and freight to San Francisco. According to Richmond historian Eleanor Ramsey, the Santa Fe Railroad company employed largely Mexican American, Japanese, and Native American workers and housed them in segregated camps. By 1902 they were over half of Richmond’s population.1

In 1901, Standard Oil built what would become the largest refinery in the western United States on Richmond’s peninsula. The refinery only hired Whites and helped stimulate a segregated industrialization, calling itself “the Pittsburgh of the West.”2 Over the next decade, a host of industries that would define America’s early industrial period located in Richmond, including the Pullman Coach Company, Ford Motor Company, and Stauffer Chemical Company. Industry lured workers, and the population grew from about 3,000 in 1900 to nearly 30,000 by the 1930s.3

The African American population grew to be the largest ethnic group in the city by the 1930s. African Americans from Louisiana and other southern states who worked as Pullman porters commonly moved their families to Richmond to avoid the racism of the American South. Discrimination continued in the labor market in California, but a growing African American workforce was willing to accept lower wages than most other workers, in part because jobs were scarce in the Jim Crow segregated South. So, families of African Americans

joined Japanese flower farmers, Chinese fishing families, and the families of the original Mexican rancheros in Richmond.

During World War II, the Kaiser Richmond Shipyards became one of the largest military shipbuilding operations in the United States. Workers, many who were Blacks recruited from the southeastern US, flocked to shipyard jobs and needed a place to live. Atchison Village, built in 1941, was one of the largest defense worker housing projects in the country. It was, like almost all government-built or subsidized housing at the time, only available to White workers. The Black, Mexican, and Japanese populations were forced to live in temporary and older housing. By 1945, Richmond had the largest public housing program in the United States, with 80 percent of Richmond’s 90,000 people living in segregated public housing.4

Racial Segregation in Richmond

Racial segregation permeated housing and employment in Richmond. In 1945 the San Francisco Chronicle reported that unemployed Black former shipyard workers were protesting the Richmond Housing Authority’s (RHA’s) decisions to deny them access to new housing. They also claimed the RHA was charging Blacks higher rents than Whites and evicting them from older public housing.5 The Steamfitters and Boilermakers Union, which controlled the majority of shipyard jobs, allowed women and people of color to be hired but denied them membership. Even when African Americans were later allowed to join unions in the mid-1940s, they were not allowed to vote in union elections and were not represented in wage negotiations.6 These racist housing and employment policies in Richmond were enforced by the city and federal governments and private industry and systematically denied African Americans, Asians, and Latinos access to the wealth and opportunities in Richmond and the Bay Area.7 African American shipyard workers sued for better wages, were represented by Thurgood Marshall, and won a landmark civil rights case in 1944 called James v. Marinship.

The racist incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII also had a significant impact on the city. Richmond was home to a number

of Japanese American families that had owned flower farm land since the 1920s and sold their flowers at San Francisco’s flower market. The land and greenhouses of all the Japanese farmers was taken, and the families were incarcerated after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued a presidential proclamation calling for the arrest and detention of all “alien enemies.” After the war, a few families, including the Fukushimas, Maidas, Oishis, and Sugiharas, returned to rebuild their farms but were forced to purchase the land they had once owned.8

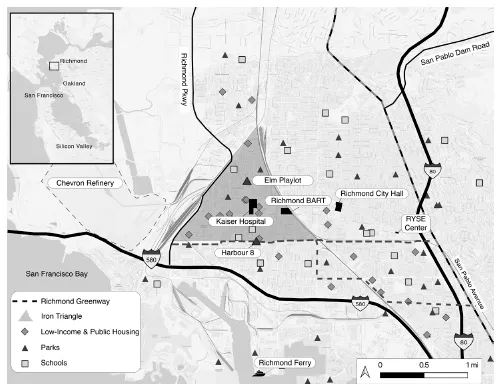

Since Richmond’s African Americans were shut out from new housing in Richmond and from moving to growing suburbs, they settled in an area called North Richmond, which remains an unincorporated area, meaning it doesn’t receive any city services or have any representation within city government. By 1950, the shipyards had closed and 36 percent of Richmond’s population was unemployed. The all-White RHA decided to evict all non-White public housing residents with the claim that their buildings were temporary and slated for demolition. Tenants went on rent strikes and the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) joined their protest efforts. By 1953, seventeen of Richmond’s public housing projects had been razed as part of the federal Urban Renewal Program.9 African American families moved into older housing in the city’s Iron Triangle neighborhood (Figure Box 1.1).

Racial Justice Activism in Richmond

The Black Panther Party for Self Defense held its first protest against racist policing in Richmond in 1967, after an unarmed, 22-year-old Black man named Denzil Dowell was shot in North Richmond. This launched the national Black Panther Party (BPP), which was fundamentally about delivering essential, life-supporting services to Blacks who were discriminated against by Jim Crow era laws and denied the means to survive.

The BPP has an important health and healing legacy, including advocating for health care as a human right; providing primary health care; operating free food, clothing, and transportation programs; developing urban gardens; advocating for affordable housing; and

organizing their own ambulance services since racist segregated hospitals refused to serve Black neighborhoods and patients.10 Of course, the BPP challenged dehumanizing policing, the unjust murdering of unarmed Black people, and mass incarceration, all issues racial and economic justice social movements have continued with today. Importantly, the BPP organized “survival conferences” where free legal services and seminars about mind, body, and health were offered, where they taught about a holistic approach to well-being that challenged the increasing dominance of the medical model of disease.11

In the 1980s, an influx of Laotian, Cambodian, Hmong, and Vietnamese refugees settled in Richmond due to US wars in Southeast Asia. The crack epidemic hit Richmond in the 1980s as did a spike in gun violence. There were sixty-two murders in 1991. The violence was also environmental; there were over 300 reported accidents, fires, spills, leaks, and explosions at the Chevron refinery from 1989 to 1995.12 Residents in the North Richmond and Iron Triangle neighborhoods—named after the railroad tracks that bordered the community—were particularly impacted by environmental pollution and gun violence.13

In the 1990s, nonprofit organizations mobilized to push back against environmental racism and structural violence. The West County Toxics Coalition, formed with the support of the National Toxics Campaign, was created by Dr. Henry Clark to protect the health and well-being of Richmond residents suffering from refinery pollution and related toxic sites in the city. Other groups, such as Opportunity West, the Asian Pacific Environmental Network/Laotian Organizing Project, Youth Together, and the Richmond Equitable Development Initiative, were created to build coalitions of residents to challenge corporate and government neglect. The RYSE Center was founded in 2008 at the request of young people in Richmond, who were demanding a safe space of their own where they could heal from the traumas of violence. New power was being built in the city to push back against long-running corporate (Chevron) control over politics, policing, and government decisions more generally.

In 2019 Richmond was home to about 110,000 people, 37 percent

of whom were White, 20 percent African American, 16 percent Asian, and over 40 percent identifying as Latino. As a “sanctuary city,” Richmond welcomes immigrants no matter their legal status. The median household income is about $64,000, compared to $71,000 in all of California, but in its poorest neighborhoods households report only $38,000 in annual income. However, many measures of well-being have improved in Richmond over the past fifteen years, including life expectancy, gun violence, and self-rated health.

Figure Box 1.1 Richmond, California, with focus on the Iron Triangle.

Box 2

Medellín, Colombia

Once the most violent city in the world, Medellín was recognized in 2013 as the most innovative city in the world by the Wall Street Journal and the Urban Land Institute and received the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize in 2016. In the 2000s, when many Latin American cities were struggling with growing levels of urban violence and inequality, Medellín was celebrated as an impressive case study of urban transformation and a model of successful public initiatives that reduced not only gun violence but also poverty, segregation, and inequality.

Medellín is the capital of the Department of Antioquia and the second-largest city in Colombia with a population of about 2.5 million. It sits in the Aburrá Valley, a region with steep mountains on its east and west sides with a river snaking along the valley floor. Within the region are ten other municipalities and a total population of about 3.7 million. Early in its development, Medellín built its wealth on gold mining and coffee exports.1 Rural violence across the region displaced farmers, and they migrated to the city.

Medellín once had a thriving industrial and manufacturing center, known by some as the Manchester of Colombia.2 However, by the 1970s there was a steep decline in manufacturing, and once-thriving textile industries left the city seeking less expensive labor in Asian countries. As Medellín’s industrial sector declined and the economy slowed, many migrants could not find formal employment, and there was a steep rise in socioeconomic inequality and growth of informal, or community-self-built housing. Large slums grew along the city’s hillsides, making life precarious for the urban poor and making it difficult for the city’s public infrastructure to reach this growing population.

In 1955, the Medellín City Council consolidated the management of its energy, public water supply, wastewater infrastructure, and telecommunications utilities into a newly formed Public Companies of Medellín (known as Grupo EPM). Owned by the City of Medellín, EPM is required by law to contribute 30 percent of its annual financial surplus (about USD 400 million in 2018) toward the city’s social development investments. This is a unique city–utility–community investment arrangement among cities globally, but particularly those in the Global South.

Colombia has had armed opposition groups, known in Colombia as guerrillas or insurgents, since at least the 1950s. This period in the country’s history, known as La Violencia, included an ideological civil war between the Conservative and Liberal parties. During this period, armed groups emerged as strongholds in certain regions, including the now infamous Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) and the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN, National Liberation Army). Other guerrilla groups operated and aimed to control an emerging drug market. By the 1980s the political insurgency and drug trafficking guerrillas were operating in urban areas, using kidnappings, bombings, and other violence to influence politics and control land-use development and the social dynamics within neighborhoods.3,4 Guerillas operating in the country’s mountains began forcing people off their land in an effort to grow more coca. The 1970s and ’80s witnessed large-scale internal displacement in Colombia, as millions were driven from rural areas into cities. According to the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), Colombia has one of the largest populations of internally displaced people around the world.5,6

According to the report, “Medellín: Memories of an Urban War,” prepared by the National Center for Historical Memory, the period from 1982 to 1994 was known as the “age of the bombs” in Medellín.7 This consumed the politics of the city and destabilized neighborhoods and most institutions, both public and private. Elected officials, union leaders, community activists, and others were kidnapped and killed by death squads.

By the 1980s, paramilitary groups and drug cartels fought over control of space and illicit markets, and rates of violence in the city began to spike well above national levels. Poverty, drug trafficking, and the heavy hand of the military combined to give Medellín the infamous title in the 1990s as the murder capital of the world. Pablo Escobar and the Medellín Cartel’s activities were at their peak in the late 1980s and early ’90s, taking over the city with guerrillas and other gangs.8 Escobar was killed in 1993, which ended his control over gangs in the city. However, smaller gangs of young people began to claim control over neighborhoods. These gangs ran local drug trafficking, but they also delivered basic services to homes where the city’s service did not reach, or refused to go, and enforced their own “extrajudicial” justice to control local disputes.9

In 1991 the homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants in Medellín was 381, the highest in the world and in any other city in the last twenty-five years.10 Yet,...