- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Maya reveals how this ancient civilization – its buildings, ideas, objects and identities – has been perceived, portrayed and exploited over five hundred years in the Americas, Europe and beyond. Megan E. O'Neil summarizes ancient Maya art and history from the Preclassic period to the Spanish invasion, as well as the history of engagement with the ancient Maya, from Spanish invaders in the sixteenth century to later explorers and archaeologists. Taking in scientific literature, visual arts, architecture, world's fairs and Indigenous activism, she looks at the decipherment of Maya inscriptions, Maya museum exhibitions and artists' responses, and contemporary Maya people's engagements with their ancestral past, to explore the history and legacy of this fascinating culture.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

| ONE ART AND ARCHITECTURE |

The civilization called the ‘ancient Maya’ or ‘Classic-period Maya’ was composed of loosely affiliated political entities that occupied many sites throughout southern Mexico and Central America for centuries. This civilization was diverse and complex, covering a large geographical region and temporal expanse, with several periods of florescence. But their world was forever transformed by the arrival in the sixteenth century of Spanish invaders, at first on the shores of the Yucatan Peninsula, in present-day Mexico. The primary subject of this book begins at that moment, considering how people have looked back at the ancient Maya civilization and endeavoured to experience, understand, frame or appropriate the culture or its artistic and architectural wonders. To help the reader appreciate these attempts at understanding, the first two chapters provide a general introduction to the ancient Maya. Nonetheless, because of the quantity and diversity of ancient Maya sites and their lengthy occupations, during which art, architecture, history and politics varied significantly, it is impossible to address here every important archaeological site or artwork, or to cover all levels of Maya society or the environmental and social conditions that enabled the ancient Maya florescence. Instead, these introductory chapters paint with broad brushstrokes a picture of the overall regions and histories, and give more detailed insight into selected artworks, places and individuals.1

When Spaniards arrived in the region that is today called Mexico and Central America, in the early sixteenth century, there were thriving Maya communities and kingdoms in the Yucatan Peninsula, Chiapas, Belize and Guatemala. The people we call ‘Maya’ were not a unified group but considered themselves as distinct families, communities or political entities. In Yucatan, the bases of political organization were the cah (plural cahob), which was a community or geographical entity, and the chibal (plural chibalob), correlating with an extended family, patronymic group or lineage. Some chibalob in the Yucatan Peninsula were the Cocom in Sotuta, the Pech in Campeche and the Xiu in Mani.2 Politically separate, they were variously in alliance or conflict. Distinct kingdoms, including the K’iche’ and the Kaqchikel, held sway in highland Guatemala, engaging with and competing against one another both before and after the Spanish Invasion.

Indeed, the people today called ‘Maya’ did not perceive a shared ethnic identity in the sixteenth century or before European arrival. But the Spaniards categorized them, along with other Indigenous Americans, as a group, as indios (Indians). The term ‘Maya’ was used in colonial Mayan-language sources but concerned references to Mayan languages. The use of the cultural category ‘Maya’ has developed over time, beginning in the colonial period and continuing during the nineteenth-century Caste Wars and in the context of twentieth-century ethnopolitics. Academic and popular attention to the ancient Maya has also contributed to creating this cultural category, and the pan-Maya movement of the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries reified this broader categorization.3 Even so, there is great diversity of language and culture of Maya people across Mexico and Central America, with more than 5 million people speaking about thirty Mayan languages.4 These diverse people speak other languages too, and live in their ancestral homelands and in diaspora in other regions of Mexico, the United States, Canada, Europe and beyond.

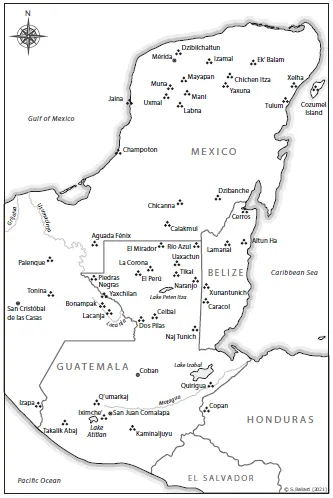

The ancient Maya flourished in several regions in the lowlands and highlands of southern Mexico and Central America. The Southern Maya Lowlands are in the Mexican states of Chiapas, Tabasco and southern Campeche; Guatemala’s Department of Peten; Belize; and western Honduras. The Mexican states of Yucatan, Campeche and Quintana Roo, in the Yucatan Peninsula, comprise the Northern Maya Lowlands. The ancient Maya flourished in the Southern Lowlands during periods called the Middle Preclassic (1000–350 BCE), Late Preclassic (350 BCE–150 CE), Protoclassic or Terminal Preclassic (150–250 CE), Early Classic (250–550 CE), Late Classic (550–850 CE) and Terminal Classic (850–1000 CE).5 The Northern Maya Lowlands were occupied during the Preclassic and Classic periods, but following the ninth-century collapse in the Southern Lowlands, civilization especially prospered in the north in the Terminal Classic and Postclassic (1000–1521 CE) periods. There was also cultural florescence in the highlands and on the Pacific Coast of southern Guatemala and Chiapas from the Preclassic to Postclassic. Important Classic-period highland sites in Chiapas are Chinkultic and Chiapa de Corzo. In the Guatemalan highlands, the large ancient city of Kaminaljuyu was founded circa 900 BCE and grew to vast proportions; that massive city was occupied into the Postclassic and is now covered by presentday Guatemala City. Other significant sites, such as Takalik Abaj, Izapa, Ujuxte, La Blanca and La Perseverancia, thrived along the Pacific coast. In the Postclassic, the Kaqchikel and K’iche’ kingdoms prospered in Guatemala’s highlands, with their capitals at Iximche’ and Q’umarkaj, respectively.

Maya region and select sites.

Scholars divide ancient Maya chronology into periods whose names – Preclassic, Classic and Postclassic – are taken from studies of European antiquity. But defining one period as ‘Classic’, those before it as Preclassic or Formative and those after as Postclassic implies formation before a more advanced era or decline afterwards. For the ancient Maya, those earlier and later periods were characterized by political complexity and significant cultural and artistic production, rendering those labels insufficient, and new research continues to challenge the connotations they carry. Indeed, it is abundantly clear that the Preclassic was a period of momentous cultural development and artistic innovation, with some of the largest structures ever built and some of the finest jadeite carving ever undertaken. Some scholars thus prefer to refer to centuries as opposed to relying on the broader terms for the periods. Nonetheless, the terms remain in use, especially to refer to larger expanses of time, and are used in this book.

Ancient Maya rulership

During the Classic period in the Maya Lowlands, political entities comparable to kingdoms or city-states elsewhere in the world shared characteristics of art, writing, religion and other aspects of culture. But there was diversity owing to chronological and regional variation and political distinction. These polities frequently competed against one another, and the epigraphic record reveals numerous examples of alliances, wars and other power dynamics. Some were able to gain control of other sites and maintain them as subsidiary allies; the subsidiary polity’s ruler acceded u kabjiiy (under the authority of) the more powerful entity. In the ancient inscriptions, toponyms identify places; for example, Lakamha’ (Big Water) is the place name for the archaeological site of Palenque, in Chiapas. But the political entity ruling that locale was identified separately with an Emblem Glyph; for Palenque, this was Baak (Bone), and Palenque’s eighth-century ruler carried the title k’uhul baak ajaw (sacred lord of Bone [kingdom]). It is now known that Emblem Glyphs could be transferred to another locale when a polity took up residence at another site; thus the same Emblem Glyph was at times used at more than one location.6

Epigraphic and artistic records indicate that Maya rulers were considered divine or semi-divine and could assume aspects of supernatural entities such as the sun, moon and Maize God. The k’uhul ajaw (sacred lord) title used for rulers derives from k’uh, the word for god or deity, implying that those with this title are godlike or filled with k’uh energy. The word ajaw, the last day name of the ritual calendar, derives from the verb ‘to shout’, referring to the importance of a leader as orator or speaker, not unlike the Mexica tlatoani (speaker) title. Rulers’ names and titles also included those of deities, such as k’inich (radiant), an honorific of the solar deity; K’awiil, a deity or manifestation of lightning and rulership; and Chahk, rain and water deity. These were generally modified to refer to aspects of those deities, such as Sihyaj Chan K’awiil (Sky-born K’awiil) and Bajlaj Chan K’awiil (Sky-hammering K’awiil), evoking the source and effects of lightning. Such naming suggests that rulers carried attributes of supernaturals that were forces of nature, such as the rain, wind and sun, and could tap into those powerful aspects of the natural world.7 Ancient depictions of rulers also suggest they were perceived to occupy the centre of the universe, at the place of the ‘World Tree’, signifying their supreme significance in the supernatural realm. Rulers and other elite individuals at times dressed as K’awiil, Chahk or the Maize God, and accompanying some images is the phrase u-baah-il a’n (it is the image in impersonation of), which is followed by the supernatural’s name, intimating that the individual has become a manifestation of that deity. Music and dance appear to have allowed individuals to tap into the power of those supernatural entities. Rulers and other elite individuals also performed ceremonies of conjuring deities and ancestors, in which offerings of blood or fire helped to summon the supernatural entity.

Depictions of significant ancestors portray them with deity attributes related to cycles of rebirth. Male and female ancestors may bear solar or lunar deity attributes, respectively, anchoring them to the daily cycles of the sun and moon. Ancestors may also bear Maize God attributes that liken them to maize, which is reborn annually. Some individuals may carry attributes of several forces of nature. The Palenque ruler K’inich Janaab Pakal – today called Pakal for short – was interred in a magnificent carved limestone sarcophagus whose lid portrays his resurrection. In that image, Pakal is depicted with characteristics of K’awiil, the Maize God and the Sun God as he rises through the solar portal from the Underworld, akin to the sun at dawn, along the axis of the World Tree.8 On the sides of the monument, his ancestors appear as fruit trees growing from the earth. Descendants publicly portrayed their links to revered ancestors through narrative texts, which connected generations by emphasizing repeated actions, or through images portraying ancestors and descendants together, either while alive or after their deaths, either symbolically present or ceremonially conjured. On both Early and Late Classic monuments, ancestors appear as supernatural entities overlooking their descendants. They also were named in textual dynastic lists, whether painted on ceramics, as on seventh-century cylinder vessels of the Kaanul (Snake) dynasty,9 or in stone, as on th...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chronology

- Notes on Spelling, Pronunciation and Dates

- Preface: A Layered Past

- 1 Art and Architecture

- 2 Places, Politics and History

- 3 Contact and Conquest, Resistance and Resilience, in the Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries

- 4 Exploration, Documentation and the Search for Origins in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

- 5 Rediscovering Maya Histories in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

- 6 Collecting and Exhibiting the Ancient Maya in the Twentieth and Twenty- First Centuries

- 7 Ancient Maya in Popular Culture, Architecture and Visual Arts

- 8 Contemporary Maya Arts, Education and Activism

- References

- Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- Photo Acknowledgements

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Maya by Megan E. O’Neil,Megan E. O'Neil in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.