This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

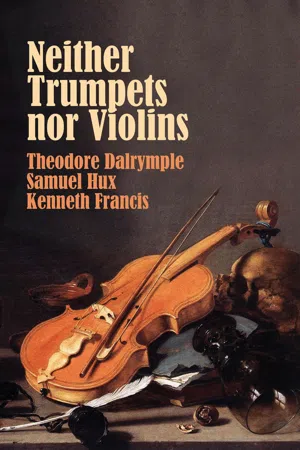

Neither Trumpets Nor Violins

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

New English Review Press once again takes on the great ideas of our time in this sequel to The Terror of Existence by Theodore Dalrymple and Kenneth Francis. This volume adds another interesting mind to the mix: the philosopher Samuel Hux. Together these thinkers take on some of the most prominent philosophers influencing our age, pointing out strengths and weaknesses in their works, worldviews. and characters. Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Sartre, Machiavelli, Plato, Schopenhauer, John Stuart Mill and Bertrand Russell are covered as are the less well-known Trumbull Stickney and Jonathan Edwards.

If you liked The Terror of Existence, you'll love Neither Trumpets Nor Violins. It's food for the mind.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Neither Trumpets Nor Violins by Theodore Dalrymple, Samuel Hux, Kenneth Francis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Ethics & Moral Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Trumbull Stickney

“SIR, SAY NO MORE:”

DEMOTING WITTGENSTEIN,

MOURNING TRUMBULL STICKNEY

SAMUEL HUX

I am tone-deaf to Ludwig Wittgenstein. I’m not proud of that fact—but I’m not embarrassed either. I am almost tone-deaf to Mozart, and I am embarrassed to admit it. I know at some necessary level (because I am not an idiot) that he is superior to Jean Sibelius, but I would rather listen to the Finnish master any day. I cannot think at the moment of any philosopher I would not prefer reading to Wittgenstein, whether one as lucid as I find William James or as beating-my-head-against-the-wall as I experience Immanuel Kant—so I am not tone-deaf to Wittgenstein because he is too difficult, but because . . . well, because I find his relative lucidity barren.

It may be that I’ve spent so much time discussing and lecturing on Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Descartes, and James (to name but a few I delight in), who tackle what I take to be the great problems of Western philosophy, that I find Wittgenstein so prickly and niggling, but I cannot be proud of the fact that I cannot follow my betters such as Bertrand Russell in discovering what made his colleague Ludwig so wonderful. Not that Ludwig appreciated Bertie’s appreciation. When the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921) was published in English in 1922, by Russell’s intervention, Wittgenstein was angry at Russell for his introduction, claiming Russell did not understand the work. If Russell did not understand Wittgenstein, who does? Certainly not I. Nor, I suspect, do his enthusiasts, much less those who think him the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century. I should emend that last sentence: they do not understand the significance of the fact that Wittgenstein is so celebrated—which judgment, however, gets me ahead of myself.

I remember being stunned several years ago by the realization that I had heard more classical concerts than had Mozart. I hear not only what’s played in concert halls but on the seldom silent radio in home or auto; Mozart, without my technological advantage, could hear only what was played in his presence. Here’s a relevant analogy: I have read more classical philosophy than Ludwig Wittgenstein. A philosophy major or minor at a respectable college or university (before at least the “relevance” revolution in higher education) has read more. Wittgenstein, finding the classical tradition of Western philosophy even into the twentieth century a large mistake, read relatively little of what he found mistaken. (This fact did not really make him an eccentric in Oxbridgean philosophical circles. Bryan Magee in his memoir, Confessions of a Philosopher, recalled how there were extraordinary gaps in the philosophical curriculum at Oxford when he was a student, great swathes of thought, Kant for instance, foreign to the anti-metaphysical bias of logical positivism and other forms of British-style “analytic philosophy.”)

While tone-deaf to Wittgenstein as I’ve confessed, I am not resistant to his (very) occasional charm. His favorite actress, according to his friend Norman Malcolm (Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir), was the “Brazilian Bombshell” Carmen Miranda—which can be read as a total lack of taste, or, as I read it, a lovable bit of insanity. And then there is one of my favorite sentences in the philosophical literature, the first proposition of the Tractatus: “The world is all that is the case.” First response: Well, what the hell else would it be? Then: Since “world” is not a geological designation, but all the somethings in coherent order, “The facts in logical space are the world,”—then what better way to say it than “The world is all that is the case?” Maybe there are better ways, but not more quirky-charming. But very quickly my patience with the Tractatus begins to recede.

I do not intend an analysis of, or another introduction to, Wittgenstein. (Should one need or want one, I know no better example of each than A.C. Grayling’s Wittgenstein: A Very Short Introduction, in the Oxford University Press short introduction series, for its readability—especially given a subject that defies the adjective readable—and given the absence of hero worship, by which I mean Grayling considers the possibility that Wittgenstein may be, instead of a great philosopher, “one of the great personalities of philosophy.”) I intend, as is already obvious, to lodge a kind of complaint, and incidentally a wonderment at the worshipful attitude of the academic profession I have myself professed—not very mainstream, I realize.

As I recall my undergraduate days at the University of North Carolina, before its philosophy department became, as I assume it did, an American island of British philosophical instruction, when it was instead a home to “Continental” philosophical biases, I have loving memories of being introduced to questions such as the nature of existence, of the soul, the limits of knowledge, the possibilities of choice, ethical standards, God or his absence, what beauty is, and-and-and the mystery of what lies beyond-behind perceivable physical reality . . . and the necessity of talking about these matters. But if I am to believe Wittgenstein, all these matters and all talk about these matters that changed my young life were merely the result of Western philosophy taking the wrong path because its practitioners did not grasp the nature of language; if philosophers made the nature of language their focus then the old questions which engaged my young mind would be shown to be spurious and would disappear. (Not quite incidentally, Martin Heidegger’s prejudice—that word intended!—that philosophy took the wrong path with Plato accounts in large for my inability to engage fully with another candidate for “greatest philosopher of the century.”)

Granted, there were modifications of the views Wittgenstein expressed in the Tractatus, those modifications appearing in his later work, most famously in Philosophical Investigations, but the “linguistic” emphasis remains, and the extraordinary reputation of W...

Table of contents

- ETitle

- Copyright page

- Epigraph

- Dalrymple on Nietzsche

- Hux on Wittgenstein-Stickney

- Francis on Schopenhauer

- Dalrymple on Wittgenstein

- Hux on Sartre

- Francis on Bertrand Russell

- Dalrymple on John Stuart Mill

- Hux on Jonathan Edwards

- Francis on Wittgenstein

- Dalrymple on Machiavelli

- Hux on Plato

- Francis on Nietzsche