![]()

Chapter 1

Hero Maker: Reframing the Principal's Role

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

"You are heroes," a uniformed police officer told a group of teachers, who reacted with a spontaneous round of applause. He was leading a lockdown drill, helping teachers practice how to respond if there were an intruder in the school or its vicinity. The officer began his presentation not by telling teachers what to do or how brave they would need to be, but by paying tribute to the consistent, quiet courage teachers already show day in and day out. He acknowledged that although the prospect of keeping company with unsavory characters at 3:00 a.m. did not faze him, he would be terrified to spend his days in a room filled with children.

Teachers are heroes.

Principals, along with other school leaders, are hero makers.

Roland Barth, founder of the Principals' Center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, is quoted as having said, "The best principals are not heroes—they are hero-makers." For us, this humble eschewing of the title of hero in favor of a supporting role is the essence of principal-coaching. Our own journeys, along with those of many other school leaders, instructional coaches, and teachers with whom we have been privileged to learn, have convinced us that fostering a school culture of instructional coaching is a potent pathway to improving the quality of learning and community in our schools. That culture begins with the principal.

Although central to school improvement efforts, the role of principal-coach is infused with paradox. Typically, instructional coaches do not have supervisory responsibilities. They are committed to supporting teacher learning using a range of approaches, including planning one-on-one with teachers, modeling, observing, and offering targeted feedback or training to teachers in their classrooms. Because instructional coaches do not evaluate, they can encourage risk taking while ensuring safety. They can support teachers through challenging times with the promise of confidentiality. By contrast, principals, ultimately accountable for the quality of learning in their schools, must set high professional expectations, evaluate teacher effectiveness, make budgetary decisions, allocate resources, assign teachers to classes, and, at times, determine whether or not to rehire a teacher.

Principals and teachers alike may wonder, How can principals possibly coach when they must evaluate? How can teachers feel safe to experiment, take risks, and reveal vulnerabilities with a person who makes important decisions about their employment? To reconcile the apparently contradictory roles of supervisor and coach, leaders must

- Reframe the role of the principal.

- Nurture a schoolwide culture of coaching and professional collaboration.

- Acknowledge the vulnerability inherent in professional learning.

Reframing the Role of the Principal

Let's consider a sports metaphor: if a school were a team, what would the principal be? Judge? Captain? Coach? Manager? Owner? Sportscaster? Physical therapist? Cheerleader? Groundskeeper? Promoter? Fan?

You could probably make an argument for any of these roles. The way we envision the varying roles of principals is as a continuum, with judge at one end and team captain at the other (see Figure 1.1). Toward the middle of the continuum stand principals who function primarily as coaches, supporting teachers' professional learning and navigating both the resulting vulnerability and the celebratory exploration integral to meaningful growth. The journey to becoming a principal-coach has the potential to transform learning for teachers in profound ways, resulting in immeasurable benefits for students. To understand the journey, it is important to consider the three main leadership approaches ranging along the continuum.

Figure 1.1. The Continuum of Principals' Roles

Judges

Principals who behave primarily as judges tend to take formal district teacher evaluation protocols seriously, striving to assess teacher effectiveness using a range of technical measurements. These principals focus on high expectations. Like the silent judges in boxing and gymnastics matches, holding up a score without explanation, principal judges rely on their evaluative tools.

This style of principal leadership is expected in many schools, but it comes with risks. Functioning primarily as judge and evaluator, even with kindness and respect, can result in a negative school culture and an unexpected decrease in school quality. Yet those who resist the role of formal evaluator run the risk of being perceived as neglecting district expectations—a potentially treacherous position for a leader.

So what is a well-intentioned, capable principal to do?

There are ways to move away from functioning primarily as a judge and toward making the evaluation process an opportunity for reflection and learning. Doing so will require leaders to find new ways to fulfill mandated procedures while either weaving them into a more reflective process or coordinating a parallel process of supportive feedback for growth. With the approval of district supervisors and leaders, the principal can accomplish such a shift, in the process delighting teachers and leading to transformative trust building and meaningful school improvement.

Team Captains

Principals who behave primarily as team captains tend to take teachers' unions seriously and strive to be advocates for teachers. Like affable peer leaders of sports teams, functioning as first among equals, principal team captains typically rely on charisma and connection. They tend to be quite popular with teachers.

Yet the team captain style of leadership also comes with risks. Embracing a comfortable camaraderie can lead to complacency, potentially stifling innovation and leading to a culture of mediocrity in which students do not receive the quality learning experiences they deserve.

Again, what is a well-intentioned, capable principal to do?

There are ways to move away from functioning primarily as a genial team captain and toward nudging teachers to seek out the joy and discomfort inherent in meaningful growth. With careful pacing, explanation, encouragement, and reassurance, principals can help teachers engage in the sometimes disconcerting yet ultimately invigorating process of reflective, substantive professional learning.

Coaches

At the middle of the continuum are principals who behave primarily as coaches, carefully balancing high expectations with robust supports. Principal-coaches see their role as learning leaders, directing resources to those areas that are most likely to affect the quality of student learning. These leaders visit classrooms and offer nonjudgmental feedback to teachers, provide time and training for teachers to work collaboratively on enhancing student learning, and creatively allocate resources in order to provide teachers with high-quality instructional coaching. Without neglecting their evaluative role, they transform formal evaluation processes into opportunities for engaged professional reflection and learning. While holding high expectations, principal-coaches support teachers as professionals and care about them as individuals.

Although shifting to a principal-coaching model has a significant positive effect on teaching and learning, it does come with some risks. District leaders may remain committed to more formal evaluative procedures. Teachers who have received exemplary or even satisfactory evaluations from leaders using the principal-judge approach may resist increasing their effort in professional learning, as a serious coaching model demands. Alternatively, teachers who have worked with principal team captains may find new expectations, even offered with support, a harsh imposition. Regardless of the prior leadership model, at least some teachers who have not experienced coaching will likely express skepticism about its benefits. They may also worry that the principal is recommending coaching because of low satisfaction with their performance rather than offering it as a gift that all professionals deserve.

So yet again, what is a well-intentioned, capable principal to do?

Although there is no recipe for transforming one's leadership style, principals can begin to reframe their role through careful and ongoing collaboration with both supervisors and teachers and a commitment to learning a number of new coaching approaches. The results can be transformative, unleashing teachers' potential and inspiring a culture of joyous curiosity about what's possible for each teacher and student.

It's true that because of their evaluative role, principals can never fully embody the role of coach. Finding balance on the continuum between judge and team captain requires ongoing navigation and adjustment. Still, although the task is challenging, we believe that supporting teachers' professional growth is the most effective way to improve the quality of our schools.

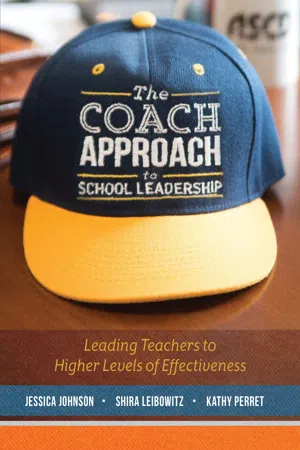

Principals wear many "hats." Throughout this book, we refer deliberately to "the coach's hat" and "the evaluator's hat." Because we firmly believe that building on teachers' strengths and helping them gain skill in areas of weakness are among the most powerful roles of a principal, our coach's hat remains our default hat—the leadership stance we use most of the time with most of our teachers. In difficult cases when we are concerned with a teacher's performance, we explain that we are speaking as a supervisor, with our evaluator's hat on, and make our expectations clear. The time to switch hats isn't always immediately obvious; we may see ineffective teaching practices that we believe will improve but instead deteriorate. At whatever point we determine coaching is no longer enough and feel deeply concerned about a teacher's performance, we must be honest with the teacher. In addition to making expectations clear, it is our responsibility to put alternative supports in place to help the teacher meet expectations. If the teacher does not improve, we owe it to our students to decide whether he or she should be retained.

Still, we see no reason to let the small number of difficult situations affect our decision to function as coach for the majority of the time, focusing on supervision for professional growth rather than judgmental evaluation.

Nurturing a Schoolwide Culture of Coaching and Professional Collaboration

Among our favorite leadership quotes is the following, often attributed to John Quincy Adams: "If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more, you are a leader." We might tweak this quote just a bit to read, "If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more, you are a teacher." Leading and teaching are not so different, after all.

We believe that coaching and professional collaboration form the link that connects great leadership, great teaching, and great learning. Thus, an essential component of principal-coaching is creating a schoolwide culture of coaching and professional collaboration. This culture involves not merely action but also interaction, not merely learning but also relationship. It stretches far beyond any one person, including the principal. Depending on the school, the central participants may include superintendents and other district leaders, assistant principals, curriculum leaders, psychologists or guidance counselors, department chairs, and teacher leaders. Ultimately, in successful cultural transformations, a majority of teachers become actively involved in crafting professional learning experiences and take ownership of their own learning.

To nurture such a culture, principals can adjust budgets to add coaching positions, reframe existing job descriptions to include some coaching components, demonstrate their appreciation for coaching, respect the confidentiality of coaches and teachers, and make clear that coaching is not remedial but a significant means of activating professional learning. Putting together a team of coaches and educational leaders who use coaching techniques is a creative process, with multiple possibilities even in budget-strapped schools. Are there specialists such as librarians, educational technology coordinators, or special education teachers whose schedules could include time for coaching? Are there teachers with expertise in particular subjects who could teach a lighter load and devote some of their time to coaching? Could job descriptions for assistant principals, curriculum coordinators, department chairs, deans, or others be modified to include coaching? Are there ways to adopt formal coaching positions, either by adding the positions if the budget allows or by repurposing existing positions?

A culture of coaching demands partnership, and there are cases in which such partnership is particularly challenging. Many coaches have asked us whether such a culture can thrive without a principal's active support. Many principals have asked us how to overcome powerful resistance among important leaders, including but not limited to the superintendent and other district leaders, school board members, teacher leaders, and teachers' unions. In these situations, educators can proceed only with caution and careful planning. Some may make the choice not to try. Others will believe that they have sufficient resources and support yet will fail and end up retreating, choosing to leave the school, or being asked to leave. Still others will try and succeed.

We have known schools in which passionate, capable coaches or teacher leaders have implemented coaching with little more than the tacit approval of the principal. We have also known principals who have withstood powerful resistance with resilience and dignity, weathering uncomfortable, even painful turbulence and making admirable progress. True transformation takes time. Even in the best cases, it is not a linear process. It requires maturity and the readiness to face numerous obstacles, especially in cultures that have long been characterized by professional isolation.

Keeping in mind that every situation and every school is different, in the following section we share three vignettes illustrating some of the challenges that principals may encounter in their quest to lead with a coach's hat.

1. When the Principal Is Not Open to Coaching

A first-year assistant principal who was primarily responsible for discipline in his school was surprised by the steady stream of students sent to his office by a single second-year math teacher. Deciding to investigate, he visited her classroom and quickly saw that although she had strong content knowledge and a warm demeanor, she lacked basic classroom management skills. After spending long hours on preparation and investing herself fully in students' success, she became frustrated when students responded to her informality with playful, disruptive banter. She would then show her agitation and habitually send students to the assistant principal. Based on informal conversations with this teacher, the assistant principal was confident that she was beginning to understand that sending students to him was undermining students' respect for her, and he anticipated that she would welcome support.

The assistant principal shared his thinking with the principal, explaining that he thought he could help this teacher by working with her much as an instructional coach would. He also shared some of his ideas for increasing collaboration among teachers: assigning master teachers as mentors for novices, creating opportunities for peer coaching, and setting up professional learning communities in which teachers could review data on students' academic and behavioral progress and work together to support student learning and growth. Teachers in the school were working in isolation, with no one entering their classrooms other than the principal, who came in once a year for a formal evaluation. They did not benefit from the observations of a supportive educator who could flag "blind spots," as instructional coaching expert Stephen Barkley calls them. In fact, they did not have anybody offering feedback on their classroom practice or helping them to improve.

The assistant principal was dismayed by his principal's reaction. The principal assured him that she would personally visit the teacher's classroom to observe the incompetence, write an unsatisfactory evaluation, and give the teacher a nonrenewal notice. She said that although she had not seen anything of sufficient concern the previous year to terminate the contract, she was certain she would now recognize the teacher's ineptitude and include it in her write-up. She also told the assistant principal that she did not want to burden him with the responsibility of coaching teachers on top of his disciplinary duties. She assured him that she was confident that in a short time, he would be able to handle all disciplinary problems promptly, keeping the school running smoothly and the teachers satisfied.

The assistant principal did not have the confidence to ask the principal all the questions he had: What purpose does it serve to evaluate teachers if you are not going to provide them with support? Why give up so quickly on a teacher with potential? What effect does accepting responsibility for discipline have on teachers as professionals? When you spend time on routine classroom discipline in one particular classroom, how much of that time would be better spent on other areas that could promote school improvement?

Several years passed, and the assistant principal grew increasingly frustrated. Eventually, he accepted a position at another school whose principal embraced his desire to incorporate coaching as a primary leadership approach. A few years later, he was hired to be a principal in another school. Among his first contributions was to create an instructional coaching program, hiring as his first instructional coaches some of the master teachers who had helped him during his first year as an administrator. Over the years, they created a powerful partnership and a culture of coaching that abounded with opportunities for active professional learning and collaboration among teachers.

2. When the Superintendent or School Board Is Not Open to Coaching

A principal who had worked as an instructional coach before being appointed to her current position reached out to a colleague in frustration. Committed to spending time in classrooms participating in learning and giving feedback to teachers, she had been instructed by her superintendent to focus on school management and formal evaluations. The...