![]()

Chapter 1

Intentional Creativity: Fostering Student Creativity from Potential to Performance

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Teachers and administrators throughout this country are focused on ensuring that both students and schools make adequate yearly progress and show growth. We order new textbooks, address curricula, concentrate professional development efforts on ways to increase student achievement, investigate new strategies to enhance students' academic progress and improve their behavior, and meet throughout the year in our professional learning communities to discuss what is and is not working. We do everything right.

However, at the end of many an academic year, schools see negligible improvements in achievement scores. Many students still act out and do not care about school. Teachers become disillusioned. Administrators face both low-performing, unmotivated students and disheartened staff. Do we need a miracle?

Perhaps it is simply that the scripted lessons teachers use are not motivating students. Veering from the scripted lesson—asking questions that promote critical and creative thinking, encouraging students to use divergent thinking to generate ideas to analyze and evaluate—might just be the key to changing students' attitudes and enhancing achievement. What many classrooms seem to be missing is creativity: creatively questioning to spark student inquiry and "hooking" student interest by using unusual images; asking students to connect content to unrelated ideas; and fostering hands-on, small-group, problem-based learning. What would happen if all teachers encouraged students to think creatively and produce creative products? Could this be the "miracle" we seek?

The idea that our educational system could use an infusion of creativity is one that has garnered much attention in recent years (e.g., Bronson & Merryman, 2010). Sir Ken Robinson's YouTube video Do Schools Kill Creativity? (2007) has had over 5 million video hits. Teachers are reading up on the basics of creativity (e.g., Beghetto & Kaufman, 2013) and watching videos that compare traditional lessons to those that require creative thinking (e.g., Ali, 2011; Maine Department of Education, 2013). Still, many educators feel that a piece is missing: precisely how to "teach" creativity and incorporate creative thinking in their classrooms. What does creativity look like, and how can schools foster it?

Creative instruction can be used to promote achievement across content areas, establish long-term learning (Woolfolk, 2007, as cited in Beghetto & Kaufman, 2010), encourage creative thinking and problem solving (Treffinger, 2008), and foster motivation and engagement. Creative thinking lessons build on critical thinking and go beyond simple recall to consider "what if" possibilities and incorporate real-life problem solving; they require students to use both divergent and convergent thinking. As Robinson has noted, "Creativity is not only about generating ideas; it involves making judgments about them. The creative process includes elaborating on the initial ideas, testing and refining them and even rejecting them" (2011, Chapter 6).

In a classroom that promotes creativity, students are grouped for specific purposes, rather than randomly, and are offered controlled product choices that make sense in the content area. Creative lesson components are not just feel-good activities. They are activities that directly address critical content, target specific standards, and require thoughtful products that allow students to show what they know. In the creative classroom, teachers encourage students to become independent learners by using strategies such as the gradual release of responsibility model (Fisher & Frey, 2008).

Creativity is not just for low-performing schools; using creative strategies and techniques helps all students think deeply and improve achievement. Creativity is not only for disengaged learners; it is motivating for all learners. Creativity is not just for students in the arts; it is for students in all classrooms in all content areas. Creativity is not just for high-achieving students; it supports struggling students and those with special needs as well. Creative thinking is not just for those students who are good at creative thinking; it is for all students. Promoting creativity in the classroom is not just for some teachers but for all teachers.

Exploring the Creativity Concept

Just what is creativity? Although creativity is often synonymous with having original ideas, definitions of the word differ. Whereas Robinson defined creativity as "a process of having original ideas that have value" (Azzam, 2009, p. 22), Gardner felt that creativity as a human endeavor does not have to be novel or of value (1989). Amabile (1989) defined a view of creativity as having expertise in a field along with a high level of divergent skills. And although some researchers hypothesize that creativity is separate from intelligence, others claim a relationship between creativity scores and IQ scores (Kim, 2005).

In addition, perceptions of creativity reflect cultural differences. Westerners generally think of creativity as novelty and emphasize unconventionality, inquisitiveness, imagination, humor, and freedom (Murdock & Ganim, 1993; Sternberg, 1985). Easterners, on the other hand, think of creativity as rediscovery and emphasize moral goodness, societal contributions, and connections between old and new knowledge (Niu & Sternberg, 2002; Rudowicz & Hui, 1997; Rudowicz & Yue, 2000). Both cultures value product creativity (Kaufman & Lan, 2012).

From a practitioner's point of view, although creative thinking is not defined solely by divergent thinking, it is associated with divergent thinking—and divergent thinking can be taught. Divergent thinking requires students to think of many different ideas, as opposed to convergent thinking, when there is only one right idea. Both are necessary for creativity: a student uses divergent thinking to generate different solutions to a problem or challenge and then uses convergent thinking to decide which one will provide the best results.

Students need to know and understand what creativity is so that they target their responses appropriately. Creativity is not just about elaborate products; it is also a way of thinking. When students hear the teacher say, "I want you to use creative thinking when you…," they should know that the teacher is looking for many ideas, different kinds of ideas, detailed ideas, or possibly a one-of-a-kind idea. Shared vocabulary and meanings are important if teachers want creativity to work.

Understanding Characteristics of Creative Students

Csikszentmihalyi (1996) described two types of creative people: "big C" creative people, those who are eminent in their field or domain and whose work often leads to change, and "little c" people, who use their creativity to affect their everyday lives. Many students do not think of themselves as creative; they believe that creativity is beyond their reach and think creativity is something that very few people engage in. They think creativity is only about big C people or students who excel in the arts. When students realize they don't have to be a big C person to be creative, then creativity becomes accessible to them. As a result of this newfound realization, students feel less pressure to come up with a one-of-a-kind idea and become willing to engage in day-to-day creative thinking activities and undertake creative products. They create realistic expectations about themselves regarding their ability to produce creatively. The more students are willing to use creative thinking, the more engaged they become.

Creative lessons instill excitement and interest, and as students become more engaged, they put out more effort. Dweck (2006) noted that students who have a fixed mindset do not believe effort and engagement make a difference; they believe they are born with a certain potential and it does not change, so they "are always in danger of being measured by failure" (p. 29). Students with a growth mindset, on the other hand, believe their skills and abilities can be developed. These students engage in hard work and demonstrate effort. When they make mistakes, they learn and grow from them. Students with a growth mindset are much more likely to use creativity as a source of engagement.

Creativity can be viewed as a cognitive style or preference: just as some students prefer to think critically, using analytical or evaluative thinking, and others prefer to use factual knowledge, certain students are inclined cognitively toward creative thinking and problem solving. In addition to differentiating instruction on the basis of student ability, interest, or learning profile (see Tomlinson, 1999), teachers also can differentiate lessons based on students' preferred cognitive style. Teachers might assign creativity activities to students who prefer to think creatively or, better yet, may group together some students who prefer creative thinking with those who prefer critical thinking.

An 8th grade social studies teacher I know was encountering behavior problems with one of her classes. She began to dread teaching this class and constantly struggled to find activities to engage the students. After asking students to rate themselves on a scale from 1 to 10 based on the characteristics of creative thinkers (see below), she found that 80 percent of the class considered themselves creative. This information was interesting to the students and very helpful to the teacher. She changed her lessons to emphasize creative thinking and creative products, and her discipline and management problems disappeared.

Creating the Classroom Climate

The starting point in the creative learning experience is the classroom and the classroom environment. Basic conditions of a creative learning classroom include providing a safe environment, supporting unusual ideas, providing choice, utilizing creative strategies and techniques, encouraging multiple solutions, incorporating novelty, and providing constructive feedback (Drapeau, 2011, p. 30). Students who learn in a creative environment, are exposed to creative activities and assignments, and observe their teacher modeling creative thinking will become more creative thinkers (Sternberg & Williams, 1996). A creative learning environment that embraces students and engagement along with critical thinking and creative thinking skills is essential to student achievement (Boykin & Noguera, 2011, 2012; Marks, 2000, as cited in Jensen, 2013).

The creation of a truly creative learning environment is deliberate. Teachers who want to see significant effects from their use of creative teaching strategies (i.e., enhanced thinking and creative processing) must make teaching creativity intentional and explicit (Higgins, Hall, Baumfield, & Moseley, 2005). In many classrooms, teachers introduce or review content but spend little time specifically naming the thinking process, describing what the process entails, or providing students with feedback as to how to improve. Their use of pure discovery and unguided instructional approaches is significantly less effective and less efficient than instructional approaches that place a strong emphasis on guiding student learning (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2010; Kirschner, Sweller, & Clark, 2006). Thus, in order to make thinking-skill instruction explicit, teachers guide student learning by naming the thinking skill in the lesson, describing how to do it well, and providing students with feedback that helps students think creatively about the content.

In the creative classroom, students recognize the relationship between the content they are studying and how they think about the content (Anderson et al., 2000). For example, when students brainstorm reasons for immigration laws, they need to know not only about immigration laws but also what brainstorming means, and how to do it well. Rubrics or feedback tools (see Chapter 7) are essential for assessing both students' content knowledge and their creative thinking skills. Using these tools also helps students see that thinking creatively about the content is as valued as content knowledge.

Unveiling the Creativity Road Map

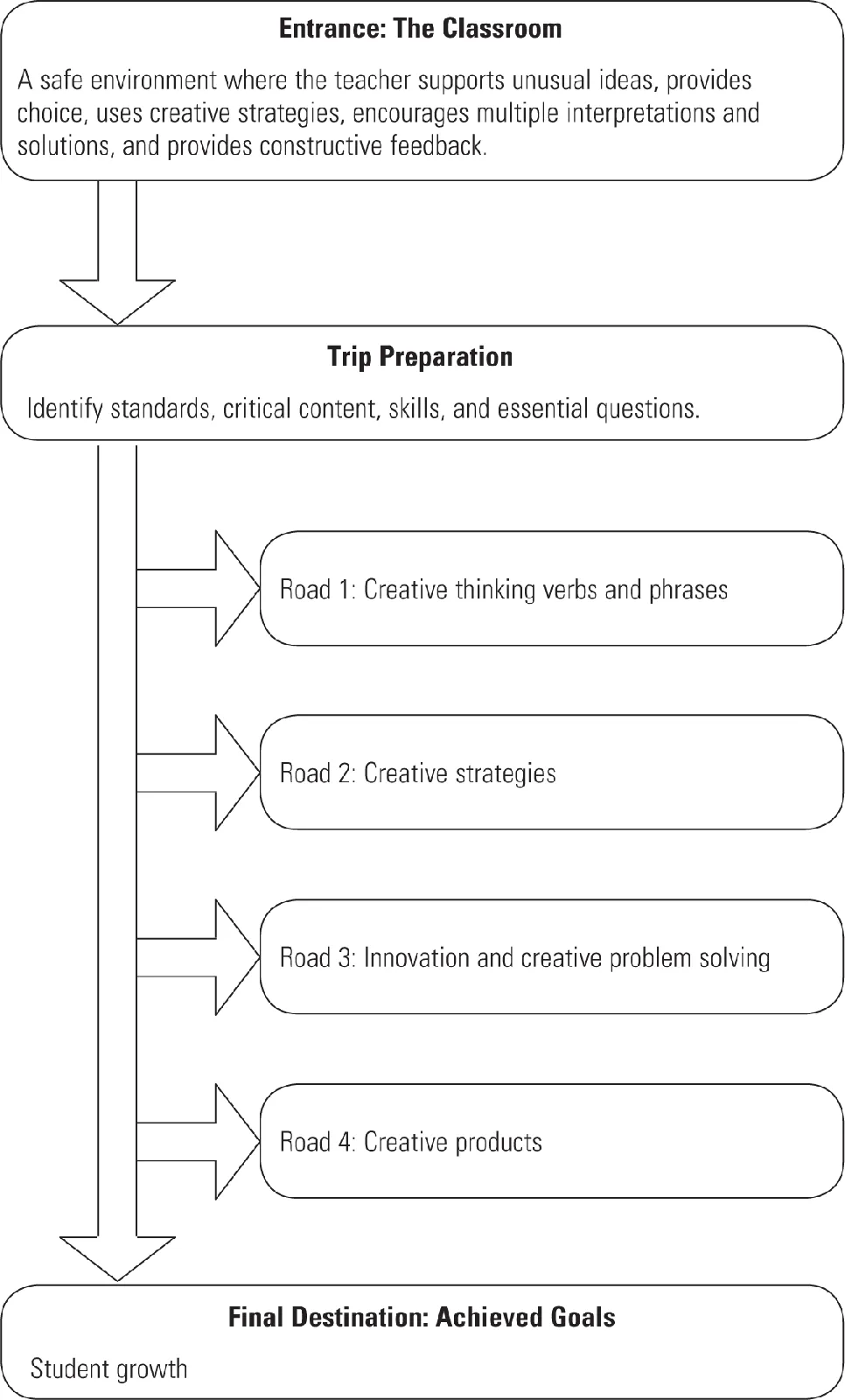

The first stop on the road to achievement is to identify the nonnegotiables. The nonnegotiables consist of the curricular standards, the required content, and the skills that are the target of a lesson (Drapeau, 2004). Then, the teacher chooses one of four roads on the Creativity Road Map (see Figure 1.1) or combines roads to intentionally integrate creative instruction with content.

FIGURE 1.1 The Creativity Road Map

Road 1: Targeting Creative Thinking Verbs

On Creativity Road 1, the focus is on creative thinking verbs and verb phrases. To promote creative thinking in the classroom, teachers pay attention to the verb in the questions they ask. Asking students to "describe the relationship between the heart and the circulation system and share the description in a paragraph" does not promote creative thinking; the verb describe directs students to merely recall known ideas. Utilizing creative thinking verbs, on the other hand, accesses creative thinking. On Creativity Road 1, teachers use verbs that encourage multiple answers, different kinds of answers, unusual answers, or elaborative answers (e.g., brainstorm, generate, connect, relate, design, create, produce, construct, elaborate, embellish, predict, improve).

For example, instead of asking students to describe the relationship between the heart and circulatory system, a teacher asks students to brainstorm all the many different types of relationships that exist between the heart and circulatory system. The thinking focus of this activity is on the creative thinking verb brainstorm. Students are expected not only to generate known ideas but also to stretch their thinking to include new ideas and possibilities. Creativity Road 1 is a good starting point for teachers who are just beginning to use creativity in their classrooms. However, it is just the beginning of the journey; creativity in the classroom requires more than substituting verbs or a verb phrase ("Grab and Go" Idea #1, Chapter 2). Interaction, sparking of ideas, and additional strategies are needed to help students produce truly creative work.

Road 2: Focusing on Creative Strategies

The second road to creative instruction is to design (or redesign) a lesson by using an instructional strategy or tool that enhances students' creative thinking skills. Direct questioning that fosters creative thinking may be effective some of the time, but a steady diet of direct questioning and whole-class instruction does not promote interaction and engagement. Instructional strategies that promote more than one answer, different kinds of answers, or unusual answers often require group activities to spark ideas. Activities that are conducive to creative thinking include

- webbing,

- brainstorming,

- problem solving,

- visualizing,

- considering points of view,

- transforming, and

- symbolizing.

The 40 "grab and go" strategies in this book help teachers of all grade levels and content areas explore creative content instruction. For the lesson on the circulatory system, the teacher could enhance the brainstorming activity by having students use the "What Stands for What" strategy ("Grab and Go" Idea #8, Chapter 2) to create an abstract symbol that represents circulation. The symbol is not the product of the lesson; rather, it serves as a prewriting tool for students to use before generating a paragraph about the topic (which is the product of the lesson).

Road 3: Using Creative Processes

Creativity Road 3 focuses on creative thinking in the procedures and processes that students use when they are focusing on creative problem solving and innovation. These processes follow certain steps that may or may not include creative activities but always include creative thinking. For example, in the circulation lesson, small groups of students might use the creative problem solving model (Isaksen & Treffinger, 1985; see discussion in Chapter 6) to explore the topic. They begin by thinking of the different problems people might encounter when dealing with a circulatory medical condition. Once students identify a specific underlying problem, they brainstorm different solutions and then determine the best solution for the underlying problem. This is one example of a step-by-step process that encourages creativity.

Road 4: Applying Creative Products

Creativity Road 4 focuses on creative products. Creative products can be simple or sophisticat...