![]()

![]()

Chapter 1

Framing the Issue of Underachievement

Start painting with fresh ideas, and then let the painting replace your ideas with its ideas.

—Darby Bannard, artist and professor

Where to Begin?

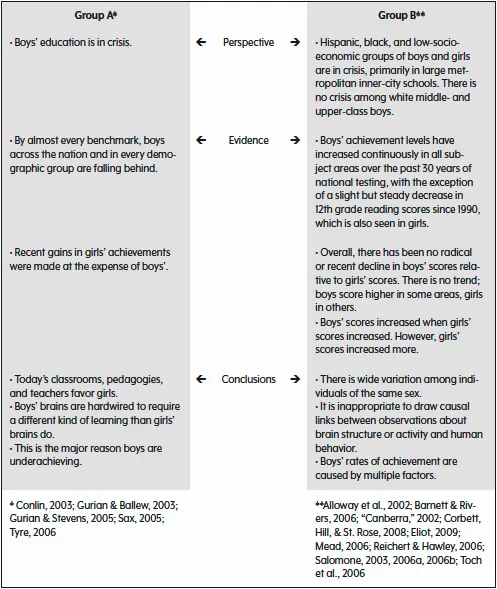

As is often the case when an area of inquiry appears straightforward and simple at the outset, my goal of sorting through the various claims about a crisis in boys' academic achievement proved far more challenging than I initially imagined it would be. During the first few months of exploration, it became clear that essentially two perspectives frame this very public debate, the proponents of which each cite research-based evidence yet reach vastly different and conflicting conclusions (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Two Conflicting Perspectives

Source: From Boys and School: Challenging Underachievement, Getting It Right! by K. Cleveland. © 2008 by TeacherOnlineEducation.com. Reprinted with permission.

Supporters of Perspective A suggest the existence of a genuine crisis in boys' education that requires a major shift in American educational policy to overcome recent gains in girls' overall achievement (which are viewed as having been made at the expense of boys' achievement). Suggested solutions include increasing boy-specific teaching strategies in coed classrooms (to counterbalance a presumed overabundance of girl-friendly pedagogy) or separating boys from girls altogether and offering the former instruction perceived as more friendly to boys' brains (Conlin, 2003; Gurian, 2001; Gurian & Ballew, 2003; Gurian & Stevens, 2005; Sax, 2005; Tyre, 2006). The major assumptions underlying this perspective are that boys' brains are hardwired differently than girls' brains, that all boys share this difference, and that the instructional strategies that help boys learn differ from those that help girls learn.

In contrast, supporters of Perspective B conclude that there is no unilateral crisis in boys' achievement, though they readily agree that achievement levels are at a crisis point among several subgroups of the male population (specifically Hispanic, African American, and economically deprived youth, particularly in major urban inner-city settings) (Alloway, Freebody, Gilbert, & Muspratt, 2002; Barnett & Rivers, 2006; "Canberra," 2002; Corbett, Hill, & St. Rose, 2008; Eliot, 2009; Mead, 2006; Reichert & Hawley, 2006; Salomone, 2003, 2006a, 2006b; Toch et al., 2006). In response to the concern that boys' learning needs have been undercut as a result of the attention given to girls' needs, Perspective B proponents point to statistics from the Department of Education showing quite the opposite: namely, that there have been no dramatic changes in boys' achievement levels during the last 30 years and that in many areas, boys' achievement has actually increased, occasionally eclipsing that of girls.

Insights from Both Perspectives

Though clearly at odds, these two perspectives each informed my inquiry in an important way. Perspective A heightened my awareness around the issue of boys and academic underachievement. The proliferation of published books and articles on this topic and a concurrent increase of attention paid to it by other mass media suggested to me that, at some level, concern about boys' underachievement was resonating strongly with the general public as well as with educators. Some perceived "truths" expressed in these publications were connecting with people deeply enough that they were buying into claims of a crisis taking shape in our schools, despite ample evidence to the contrary. I wondered what those "truths" were.

Perspective B engaged me in exploring more deeply the research used to justify conclusions on both sides of the debate. I realized that even though there might not be a genuine crisis, there were, nonetheless, specific aspects of the American education system with which many boys still struggled. Achievement trends aside, too many boys were not reaching expected levels of success, and the problem was both widespread and serious.

When in frustration I eventually abandoned my fruitless attempts to reconcile these two opposing perspectives, a gift emerged from the detritus of my efforts. I realized that the problem of underachievement was not a gender-wide crisis needing a gender-wide one-size-fits-all-boys solution. Indeed, the problem didn't even encompass all boys. Instead, the real issue was finding ways to identify and respond to the specific reasons for underachievement among the boys still struggling in our classrooms and schools despite our best efforts: the boys who fall behind and stay behind, the boys who drop out too soon, and the boys we just never seem to reach. There had to be a way to help these specific boys without jeopardizing the achievements of other, more successful learners (boys and girls), and this would turn out to be a vastly different proposition than the one I had originally envisioned.

This shift in my perspective also altered the trajectory of my inquiry. As my focus moved away from all boys and toward struggling boys in particular, I recognized that I needed to learn more about the specific ways in which boys struggle in our classrooms. I also wanted to examine how the way we "do school" might be interfering with an underachieving boy's potential for achievement. And with the latter consideration came a secondary realization that the solutions used by each teacher would need to be as different as the teachers and their students. In other words, their problems were unique, and the solutions to those problems must necessarily be unique as well. Finding solutions would mean helping educators find ways to respond flexibly and effectively to the challenges their underachieving boys were facing in their classrooms.

A Look at the Problem Through Educators' Eyes

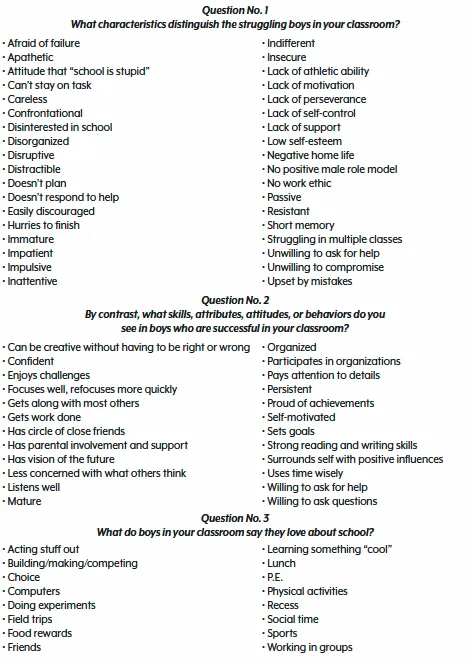

To reframe my understanding of these complex issues, I acted much as an artist might when nothing seems to be working: I went back to the proverbial drawing board and began anew with a fresh canvas. I consulted educators currently working in the field, who deal with the problem of boys' underachievement on a daily basis, hoping that a new "rough sketch" of the issue might emerge from their shared observations. I asked these classroom teachers, administrators, and counselors from all grade levels and subject areas to answer the following questions about underachievement among boys, based on their own experiences. I encourage you to take a moment to answer these questions for yourself before you read on.

- What characteristics distinguish the struggling boys in your classroom?

- By contrast, what skills, attributes, attitudes, or behaviors do you see in boys who are successful in your classroom?

- What do boys in your classroom say they love about school?

- What do boys in your classroom say they hate about school?

- What would boys in your classroom say they are most successful at?

- Are there any aspects of the subject you teach that seem to be obstacles to academic success for a large number of boys?

- What aspects of teaching boys are most challenging for you?

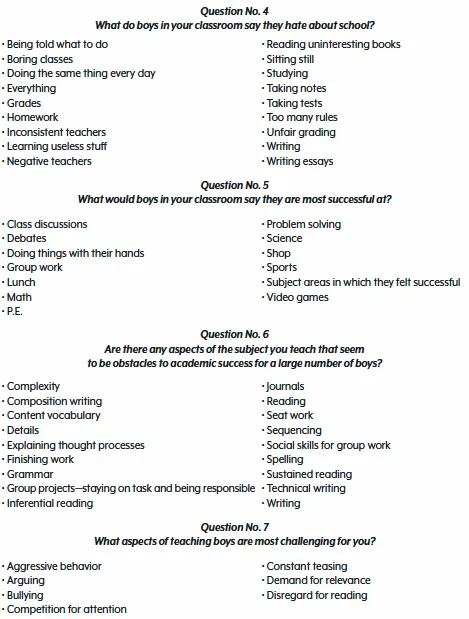

The collective responses I gathered uncovered valuable clues in four key areas regarding the dilemma of academic underachievement among boys (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Survey Responses

Figure 1.2. Survey Responses (continued)

Source: From Boys and School: Challenging Underachievement, Getting It Right! by K. Cleveland. © 2008 by TeacherOnlineEducation.com. Reprinted with permission.

Clue No. 1: The influence of nonacademic factors on academic success. With regard to differences between academic skills, there were no surprises when I compared responses to the first question (What characteristics distinguish the struggling boys in your classroom?) with those to the second question (By contrast, what skills, attributes, attitudes, or behaviors do you see in boys who are successful in your classroom?). The descriptions of successful boys included critical academic skills such as listening, organizing, focusing, using time wisely, paying attention to details, reading and writing well, and finishing assigned tasks.

What I found especially interesting, though, were the nonacademic factors teachers mentioned when characterizing their high-achieving boys. These factors fell into three general categories: social confidence (e.g., "has circle of close friends," "gets along with most others," and "participates in organizations"); attitudes about self and learning (e.g., "enjoys challenges," "confident," "persistent," "proud of achievements," and "willing to ask for help"); and access to support systems (e.g., "has parental involvement and support" and "surrounds self with positive influences").

I wondered if the familiar negative behaviors we view as causes for underachievement might, in fact, diminish if underachieving boys were privy to the protective benefits that these seemingly nonacademic factors offer to their more successful male peers. Were underachieving boys disruptive, resistant, confrontational, or uninterested, for example, because "that's just how some boys are and there's nothing one can do about it," or were these behaviors the result of not having access to support systems that could build social confidence and positive attitudes about self and about learning? Could these missing or undeveloped attributes provide educators with a road map for helping struggling boys?

Clue No. 2: Factors contributing to the "experience" of school. Among the responses to questions three (What do boys in your classroom say they love about school?), four (What do boys in your classroom say they hate about school?), and five (What would boys in your classroom say they are most successful at?), I caught glimpses of several additional factors with the potential to affect a boy's academic success.

It was evident that what was alternately valued or reviled by many boys had much to do with the experience of school. The type and qualities of their interactions with peers and teachers seemed to affect boys' perspectives about school in general. On the one hand, what seemed to make school worth their time and effort revolved around the quality and frequency of interactions with friends. On the other, what made school a less than welcoming experience had to do with the teacher-student relationship, the kinds of instruction used, and the classroom setting itself. I wondered how much a feeling of belonging had to do with an underachieving boy's ability to engage in academic learning and if an absence of this feeling might negatively affect his behavior, his attitudes about school in general, and his perceptions about himself as a capable learner.

I noticed, too, that lack of success in certain content areas contributed to the degree of a boy's negativity about school in general. I wondered if there might be ways to help underachieving boys feel more successful as learners and how significant a piece of the equation this was. Were there ways to "do school" differently that might catch more boys before they fell through the cracks and make them want to stay?

Clue No. 3: How competence can enhance persistence. The responses to question six (Are there any aspects of the subject you teach that seem to be obstacles to academic success for a large number of boys?) seemed to home in on how hugely important literacy skills (i.e., reading, writing, grammar, composition, vocabulary, spelling) are to academic success, regardless of a teacher's subject area or grade level. These responses raised two additional questions for me. I wondered, first, why so many boys struggle with literacy and if there were approaches that might help these literacy-challenged learners find more success with this crucial task. Second, I wondered how strongly a boy's feelings of inadequacy about his literacy skills affected his willingness to persist in acquiring them. Would addressing literacy in ways that a boy could more fully embrace improve his overall feeling of competence and his willingness to persevere? Would this, in turn, affect a boy's attitudes about learning in general and about himself as a learner?

Clue No. 4: How a classroom's physical arrangement impacts a learner's success within it. The responses to question seven (What aspects of teaching boys are most challenging for you?) brought a final, equally important consideration to the fore. I wondered how factors within the physical environment of the classroom (e.g., lighting, seating, room arrangement) might affect a boy's academic achievement. Were aspects of the physical arrangement of the classroom exacerbating the problems of underachieving boys, and were some of the characteristic negative behaviors we associate with them the result of these elements? Could the classroom be reconfigured to allow underachieving boys to function better within it?

A New Direction

Social confidence, attitudes about self and learning, access to support, connections between competence and persistence, and a classroom's physical configuration—these were very different considerations than those proffered on the exhaustive lists of purportedly brain-based explanations for boys' underachievement I'd been reading. And though I had more questions than ever, I recognized that addressing the question of academic underachievement in boys would not be as simple as identifying gender-specific factors (i.e., boys' brain chemistry or hormones) or the academic part of the equation (what and how we teach). It would be about comprehending how a host of factors come together to support a struggling boy as a learner and the ways in which his needs are met in the contexts of school, classroom, relationships, and learning experiences.

To this end, a set of overarching goals emerged that provided a pathway for leading the struggling boy away from underachievement and toward his potential, not by catering to his deficits, but by building on his strengths:

- Replace his negative attitudes about learning with productive perspectives about the role of risk (and even failure) as a necessary and valued part of the learning process;

- Reconnect him with school, with learning, and with a belief in himself as a competent learner who is capable, valued, and respected;

- Rebuild life skills and learning skills that lead to academic success and also lay the groundwork for success...