![]()

Chapter 1

Learning, or Not Learning, in School

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Learning—the goal of schooling—is a complex process. But what is learning? Consider the following definitions and the implications each has for teaching:

- Learning is the process of acquiring knowledge or skill through study, experience, or teaching.

- Learning is experience that brings about a relatively permanent change in behavior.

- Learning is a change in neural function as a consequence of experience.

- Learning is the cognitive process of acquiring skill or knowledge.

- Learning is an increase in the amount of response rules and concepts in the memory of an intelligent system.

Which definition fits with your beliefs? Now ask yourself, how is it that you learn? Think of something that you do well. Take a minute to analyze this skill or behavior. How did you develop your prowess? How did you move from novice to expert? You probably did not develop a high level of skill from simply being told how to complete a task. Instead, you likely had models, feedback, peer support, and lots of practice. Over time, you developed your expertise. You may have extended that expertise further by sharing it with others. The model that explains this type of learning process is called the gradual release of responsibility instructional framework.

The Gradual Release of Responsibility Instructional Framework

The gradual release of responsibility instructional framework purposefully shifts the cognitive load from teacher-as-model, to joint responsibility of teacher and learner, to independent practice and application by the learner (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983). It stipulates that the teacher moves from assuming “all the responsibility for performing a task … to a situation in which the students assume all of the responsibility” (Duke & Pearson, 2002, p. 211). This gradual release may occur over a day, a week, a month, or a year. Graves and Fitzgerald (2003) note that “effective instruction often follows a progression in which teachers gradually do less of the work and students gradually assume increased responsibility for their learning. It is through this process of gradually assuming more and more responsibility for their learning that students become competent, independent learners” (p. 98).

The gradual release of responsibility framework, originally developed for reading instruction, reflects the intersection of several theories, including

- Piaget's (1952) work on cognitive structures and schemata

- Vygotsky's (1962, 1978) work on zones of proximal development

- Bandura's (1965) work on attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation

- Wood, Bruner, and Ross's (1976) work on scaffolded instruction

Taken together, these theories suggest that learning occurs through interactions with others; when these interactions are intentional, specific learning occurs.

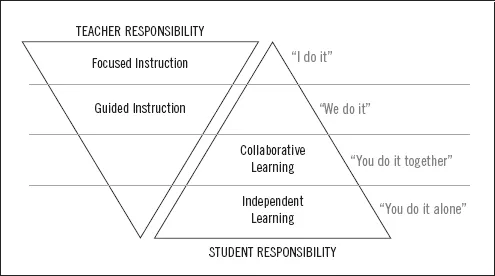

Unfortunately, most current efforts to implement the gradual release of responsibility framework limit these interactions to adult and child exchanges: I do it; we do it together; you do it. But this three-phase model omits a truly vital component: students learning through collaboration with their peers—the you do it together phase. Although the effectiveness of peer learning has been demonstrated with English language learners (Zhang & Dougherty Stahl, 2011), students with disabilities (Grenier, Dyson, & Yeaton, 2005), and learners identified as gifted (Patrick, Bangel, & Jeon, 2005), it has typically been examined as a singular practice, isolated from the overall instructional design of the lesson. A more complete implementation model for the gradual release of responsibility recognizes the recursive nature of learning and has teachers cycle purposefully through purpose setting and guided instruction, collaborative learning, and independent experiences. In Figure 1.1, we map out these phases of learning, indicating the share of responsibility that students and teachers have in each.

Figure 1.1 | A Structure for Instruction That Works

We are not suggesting that every lesson must always start with focused instruction (goal setting and modeling) before progressing to guided instruction, then to collaborative learning, and finally to independent tasks (Grant, Lapp, Fisher, Johnson, & Frey, 2012). Teachers often reorder the phases—for example, begin a lesson with an independent task, such as bellwork or a quick-write, or engage students in collaborative peer inquiry prior to providing teacher modeling. As we stress throughout this book, what is important and necessary for deep learning is that students experience all four phases of learning when encountering new content. We will explore these phases in greater detail in subsequent chapters, but let's proceed now with an overview of each.

Focused Instruction

Focused instruction is an important part of the overall lesson design. This phase includes establishing a clear lesson purpose. We use the word purpose rather than goal, objective, or learning target because it's essential to ensure that students grasp the relevance of the lesson. The statement of a lesson's purpose can address goals related to content, language, and social aspects. Consider, for example, the teacher who clearly communicates the purpose of a lesson as follows:

Our content goal today is to multiply and estimate products of fractions and mixed numerals because these are used in cooking, construction, and medicine. Our language goal for today is to use precise mathematical terminology while discussing problems and answers with one another. Our social goal today is to improve our turn-taking skills by making sure that each member of the group has a chance to participate in the discussion.

As Dick, Carey, and Carey (2001) remind us, an “instructional goal is (1) a clear, general statement of learner outcomes, (2) related to an identified problem and needs assessment, and (3) achievable through instruction” (p. 25). These are important considerations when establishing lesson purpose. As we will discuss further in Chapter 2, it's not enough to simply state the lesson purpose. We must ensure that students have opportunities to engage with the purpose in a meaningful way and obtain feedback about their performance.

In addition to establishing purpose, the focused instruction phase of learning provides students with information about the ways in which a skilled reader, writer, or thinker processes the information under discussion. Typically, this is done through direct explanations, modeling, or think-alouds in which the teacher demonstrates the kind of thinking required to solve a problem, understand a set of directions, or interact with a text. For example, after reading aloud a passage about spiders to 3rd graders, a teacher might say:

Now I have even more questions. I just read that spiders don't have mouth parts, so I'm wondering how they eat. I can't really visualize that, and I will definitely have to look for more information to answer that question. I didn't know that spiders are found all over the world—that was interesting to find out. To me, the most interesting spider mentioned in this text is the one that lives underwater in silken domes. Now, that is something I need to know more about.

Focused instruction is typically done with the whole class and usually lasts 15 minutes or less—long enough to clearly establish purpose and ensure that students have a model from which to work. Note that focused instruction does not have to come at the beginning of the lesson, nor is there any reason to limit focused instruction to once per lesson. The gradual release of responsibility instructional framework is recursive, and a teacher might reassume responsibility several times during a lesson to reestablish its purpose and provide additional examples of expert thinking.

Guided Instruction

The guided instruction phase of a lesson is almost always conducted with small, purposeful groups that have been composed based on formative assessment data. There are a number of instructional routines that can be used during guided instruction, and we will explore these further in Chapter 3. The key to effective guided instruction is planning. These are not random groups of students meeting with the teacher; the groups consist of students who share a common instructional need that the teacher can address.

Guided instruction is an ideal time to differentiate. As Tomlinson and Imbeau (2010) have noted, teachers can differentiate content, process, and product. Small-group instruction allows teachers to vary the instructional materials they use, the level of prompting or questioning they employ, and the products they expect. For example, Marcus Moore,* a 7th grade science teacher, identified a group of five students who did not perform well on a subset of pre-assessment questions related to asteroid impacts. He met with this group of students and shared with them a short book from the school library called Comets, Asteroids, and Meteorites (Gallant, 2000). He asked each student to read specific pages related to asteroids and then to participate in a discussion with him and the others in the group about the potential effect that these bodies might have on Earth. During this 20-minute lesson, Mr. Moore validated and extended his students' understanding that, throughout history, life on Earth has been disrupted by major catastrophic events, including asteroids. At one point in the group's discussion, he provided this prompt:

Consider what you know about the Earth's surface. Talk about that—is it all flat? (Students all respond no.) What do you think are the things that made the surface of the Earth look like it does? Remember, the Earth has a history….

A single guided instructional event won't translate into all students developing the content knowledge or skills they are lacking, but a series of guided instructional events will. Over time and with cues, prompts, and questions, teachers can guide students to increasingly complex thinking. Guided instruction is, in part, about establishing high expectations and providing the support so that students can reach those expectations.

Collaborative Learning

As we have noted, the collaborative learning phase of instruction is too often neglected. If used at all, it tends to be a special event rather than an established instructional routine. When done right, collaborative learning is a way for students to consolidate their thinking and understanding. Negotiating with peers, discussing ideas and information, and engaging in inquiry with others gives students the opportunity to use what they have learned during focused and guided instruction.

Collaborative learning is not the time to introduce new information to students. This phase of instruction is a time for students to apply what they already know in novel situations or engage in a spiral review of previous knowledge.

It is important, too, that you allow collaborative learning to be a little experimental, a little messy. In order for students to consolidate their thinking and interact meaningfully with the content and one another, they need to encounter tasks that will reveal their partial understandings and misconceptions as well as confirm what they already know. In other words, wrestling with a problem is a necessary condition of collaborative learning. If you are pretty certain your students will be able to complete a collaborative learning task accurately the first time through, that task would probably be better suited to the independent learning phase.

Collaborative learning is also a perfect opportunity for students to engage in accountable talk and argumentation. Accountable talk is a framework for teaching students about discourse in order to enrich these interactions. First developed by Lauren Resnick (2000) and a team of researchers at the Institute for Learning at the University of Pittsburgh, accountable talk describes the agreements students and their teacher commit to as they engage in partner conversations. These include staying on topic, using information that is accurate and appropriate for the topic, and thinking deeply about what the partner has to say. Students are taught to be accountable for the content and to one another, and they learn techniques for keeping the conversation moving forward, toward a richer understanding of the topic at hand. The Institute for Learning (n.d.) describes five indicators of accountable talk:

- Press for clarification and explanation (e.g., “Could you describe what you mean?”).

- Require justification of proposals and challenges (e.g., “Where did you find that information?”).

- Recognize and challenge misconception (e.g., “I don't agree, because _______________.”).

- Demand evidence for claims and arguments (e.g., “Can you give me an example?”).

- Interpret and use one another's statements (e.g., “I think David's saying _______________, in which case, maybe we should _______________.”).

These are important skills for students to master and, on a larger scale, valuable tools for all citizens in a participatory democracy (Michaels, O'Connor, & Resnick, 2008). They are also key to meeting Common Core State Standards in speaking and listening, the first of which asks students to “prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively” (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers [NGA/CCSSO], 2010a, p. 22).

We have seen teachers integrate collaborative learning opportunities into their instruction in a variety of ways. For example, a 10th grade social studies teacher selected a number of readings that would allow his students to compare and contrast the Glorious Revolution of England, the American Revolution, and the French Revolution. The students did so through reciprocal teaching (Palinscar & Brown, 1984), an arrangement in which groups of students read a piece of text in common; discuss the text using predicting, questioning, summarizing, and clarifying; and take notes on their discussion. At the end of the discussion, each student in the class summarizes the reading individually—a step that ensures the individual accountability that is key to successful collaborative learning.

The way in which one of these groups of students talked about their reading demonstrates how peers can support one another in the consolidation of information:

Jamal: I still don't get it. Those folks in England had a revolution because the king wanted the army to be Catholic, and he got his own friends in government. But I need help to clarify what they mean by the “Dispensing Power.” It sounds all Harry Potter.

Antone: I feel yo...