![]()

Chapter 1

The Big Four

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Gary Nunnally, a secondary social studies/history teacher in Nebraska, was participating in a staff development seminar on instructional strategies. Sitting in the back row with his leg in a cast, Gary appeared to be giving Jane, one of the authors of this book, the dismissive "talk to the hand" signal with the underside of his foot. It was fitting, given the heated exchange they were about to have about teaching, learning, and homework. Every time she would suggest how to use one of the research-based instructional strategies, Gary responded that he might try it if it would motivate the students to finish their homework. He said that he could only do so much in class, but students needed to take responsibility to complete all homework assignments to get good grades. At one point he argued that he could not even plan daily lessons because the following day relied on students completing homework. Gary noted that his students' disinterest in completing work was the cause of behavioral problems in his classroom, plummeting grades in his course, and, by extension, many uncomfortable parent–teacher conferences.

After his many interruptions, Jane asked Gary if he could possibly identify the number of students in each class who were not performing to the level that he expected—that would be a start in a positive direction. Without hesitating, Gary responded that there were four or five students he called "the disengagers" because they were attending but just did not participate fully in the class. He added that it meant that over the course of a day, 5 students per class added up to 25, or almost a class itself! When they opened the question to the other teachers from all grade levels in the session, it seemed that they, too, identified four or five students in every class who by their judgment should be performing better. Depending on the grade levels or subjects, teachers surmised reasons mostly related to factors outside of the classroom. Teachers agreed they wanted to find a way to improve learning with strategies that would help the four or five students in every class, but they stated their commitment to improving learning for all children. What was so impressive was that all of the teachers took personal responsibility; they described how they constantly tried harder to find new ways to help the students, hoping that those new ways would work, even if it was not a school or a district initiative. It seemed to us that they were initiating reforms one teacher at a time.

Gary offered that he wanted to take the "hope" out of his classroom. "I do not want to hope that the students will do well; I want to be able to plan for it to happen and be glad when I see the results for every student in my classes."

Replacing Hope with Certainty

"Take hope out of schools" would seem an unusual slogan for someone who wants to improve student learning. But, recall how many times you and your colleagues are likely to have said, "I hope this lab works; I spent a lot of time collecting the specimens and setting it up for my students." "I hope the students can identify the adverbs and adjectives on the test; I spent so much time reviewing." "I hope that tonight's concert goes well; I worked so hard and went over every piece again in today's rehearsal."

Over the years, one can see how schools take on improvement initiatives, specifically regarding structural reforms such as scheduling or student groupings, special programs, new technologies, and creative resources. All of them contribute enormously to improving the system but unfortunately fall short on the student achievement gains, as those do not seem to increase significantly. In this book, we share what we learned when we listened to individual teachers tell us what was working, but also what they were willing to slightly adjust when we shared new research. We focus on using research about teaching and learning to help teachers like Gary, who works really hard but gets frustrated with students who do not participate. It may also be helpful to new teachers who struggle to find efficient routines and ways to use time better in class.

To take hope out of school and replace it with certainty, we revisited the classic framework that guides teaching and learning: curriculum, instruction, and assessment. To our surprise, it appeared to be missing the one piece that can actually increase student performance.

The Missing Piece

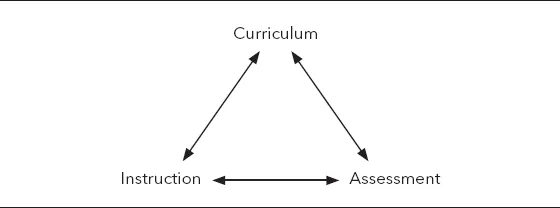

Remember the diagram in the teaching text that showed the three points of a triangle labeled with the terms curriculum, instruction, and assessment? The lines were arrows indicating the interconnectedness of the three (see Figure 1.1). The promise of this framework was that teachers would teach and assess to the curriculum, creating the perfect feedback loop in which all students would learn.

Figure 1.1. The Curriculum-Instruction-Assessment Model

Listening to teachers like Gary Nunnally, we know that is not true for all students. We began with curriculum. Most teachers, Gary commented, say that curriculum documents are wordy and formatted in lengthy, boxy columns. Because they are difficult to read, they do not serve to guide instruction on a daily basis. He said that after perusing them at the beginning of the year, they sit on shelves collecting dust or hide away in digital files. Because of past experiences, many teachers have developed a "this too shall pass" mentality when new standards appear or new curriculum initiatives begin. What teachers want, he said, is curriculum documents reformatted for better accessibility, brevity, and readability. Can we make the documents in such a way that, instead of having a long multipage document, they could be in separate files because we now have access to shared document files?

As far as instruction, or planning lessons, Gary admitted that over the years he learned that he needed to plan for the student activities. Unit planners, he said, often offer standards with lists of optional instructional activities. If you looked at his planning, he would describe the task that the students would do that day or for homework and any possible assessment opportunities. After writing the lessons, he would go back to the list of standards and attach the ones that were relevant as the standards for that day; often there were as many as four or five that seemed to fit each day. With so many, it did not seem viable to track student progress back to the standards—the lesson, yes, but not individual progress. That means that there could be a gap in the curriculum-instruction-assessment feedback loop that might be contributing to the "missing piece."

For assessment, Gary committed to providing two review days to ensure that students would do better on the summative unit or quarterly tests. Did they? Some, he told us, but not all students did well even though he also provided comprehensive review sheets. Retesting? No time if he wanted to cover the curriculum. Quizzes? No time for them as there was already enough testing with state tests taking up so much time. The elementary teachers were less likely to give assessments, per se, as they felt they were assessing a lot of the time, just not writing it down. Sometimes they were asked to use standards-based report cards, but since they only specified a few standards, they did not really track progress daily.

To recap, teachers have curriculums, but because they are dense or use unfriendly formats, teachers tend to be able to teach without closely following them. Teachers often plan activities as their lesson planning; importantly, they often choose standards after planning, so they might not teach them explicitly. Most teachers tell us that they design their own assessments or build them online, and they would not assess what they do not find time to teach. That could mean that some standards in the curriculum may not be assessed in depth or possibly at all. Time is always an issue, and the perception that there is too much assessment anyway discourages many teachers from adding formative assessment. As a result of these three issues, few teachers tell us that they score student work to the standards identified by the curriculum—and that detail provided the missing link that led us to create the Big Four.

We hypothesized that teachers need

- Curriculum documents formatted in a way that helps them pace the standards and the unpacked objectives,

- A schema for lesson planning and delivery that describes what they would do as well as what the students should do to be more engaged with learning in class,

- More formative assessment with more open-ended response opportunities directly tied back to the standards, and

- Multiple methods to provide students with productive feedback about individual progress on the standards.

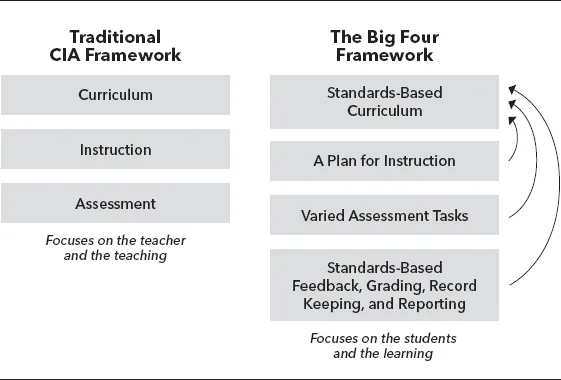

The intention of curriculum-instruction-assessment was a pathway that focused on the teacher and the teaching, but the framework was inadvertently missing an explicit feedback loop that would directly connect the learner to the learning goals. The Big Four is a framework that intends to link student performance directly to the curriculum, instruction, and assessment; the update includes a fourth component that we refer to as "feedback to the standards."

The Big Four

The Big Four keeps what works in the curriculum-instruction-assessment model but shifts the focus toward providing feedback to the students about their progress on the standards:

- Curriculum should be ambitious and accessible. Curricula should provide the content standards by grade levels, subjects, or courses distributed by reporting periods and by units of study. At the unit level, the standards need to be unpacked to daily learning objectives so that teachers can plan daily instruction and assessment. This provides the foundation for productive instructional planning and intentional goal-based feedback for students in the classroom every day.

- Instruction should be research-based and student-centered. Teachers should plan lessons so students (1) use strategies shown to have a high probability for improving content retention and skills, (2) increase their capacity to learn independently, and (3) learn to seek productive feedback. The instruction should directly tie back to the standards and unpacked objectives; each teacher has the autonomy to design lessons, select resources, and vary delivery methods.

- Assessment should maximize feedback and require critical and creative thinking. Teachers should use formative assessment to provide timely feedback, redesign assessments to require critical and creative thinking skills, and judge performance on summative assessments by standards. All assessment should directly tie back to the curriculum standards, providing the scaffolds and modifications for students to self-assess and show their best work.

- Feedback should track and report student progress by standards. Teachers should use the standards-based student data gathered through formative assessment to personalize feedback, motivate improvement, and differentiate instruction for students. Equally important, it should provide accurate evidence of student learning that can be communicated to specialists, parents, and caregivers.

Many teachers will say that they already implement the Big Four. Yes, they have a curriculum, create lesson plans, use assessment techniques, and give grades. But if we ask the same teachers if all of the students perform to expectations or to the standards, most will say that they do not. A significant shift from the curriculum-instruction-assessment model to the Big Four is that teachers gauge student performance on the curriculum standards and objectives as an interactive part of instruction and assessment on a daily basis (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. From Traditional Framework to the Big Four

Not a New Idea

Nanos gigantum humeris insidentes, or "each generation stands on the shoulders of those who have gone before them," is an important lesson. Gary, the history teacher, asked why our generation of teachers has to use standards-based curricula or give assessments when teaching should be more of an art. The implication is that we are the first or only ones to have to do it. But, many great teachers came before us, and to deeply understand the framework we call the Big Four, we revisit a few of the foundational elements that led to where we are today. Although there is a vast history of teaching, we chose a few of the milestones that directly tie teaching to initiatives to improve learning for all students. Remember, also, that Gary is a history teacher, so he needed to piece together the chronology; as a reader, you can skip this part if you want to get right to work on curriculum writing in Chapter 2, lesson planning in Chapter 3, assessment development in Chapter 4, or feedback approaches in Chapter 5.

In the early years of European settlement in Massachusetts, the purpose of education was to teach children to read and interpret the Bible. The Old Deluder Satan Act of 1647, and similar acts in other states, required all towns of 50 or more children to provide a community school (Ornstein, Levine, & Gutek, 1993). The intention was that all children should learn to thwart the dangerous Satan for their own well-being and for the good of the township. That law established the principles for schooling in the United States today, where the community funds and shares the responsibility for learning. Schools would prepare students through secondary school so they could attend colleges. But, despite good intentions, not all children were welcome in these schools, and those who were allowed to attend were not always able to stay in school, as they had farming, family, and later, factory duties.

More than a hundred years later, the third president, Thomas Jefferson, envisioned a country in which all citizens would be educated. Jefferson, wary of monarchial government, believed that every person should go to school to learn in order to be able to make an educated vote. To that end, schooling for all children would be the ultimate goal. As in previous generations, not all students attended school, but by the early 1900s, education laws were passed to ensure the opportunity for learning for all children. The conclusion we drew from history was that, in spite of the intention that all children would have the opportunity to go to school, many out-of-school factors prevented children from attending or completing school.

As the country edged into an Industrial Revolution at the turn of the 20th century, the need for technical education to prepare workers for specialized occupations challenged the "general knowledge" approach of schooling. This point in history pivoted the purpose for schooling to a new question: Do we design curricula that are primarily vocational in nature or primarily academic? A Committee of Ten, and later, the Commission on the Reorganization of Secondary Education, addressed the question of education's purpose in the United States. There was a general consensus that education's purpose was twofold: to support classical academics and provide readiness for the workplace. With that in mind, more children would be likely to attend school. The notion of academic and vocational programs would contribute to increased attendance and graduation rates.

World War II ended, and with the spirit of prosperity, Ralph Tyler produced an important brief that would become the pillar of school improvement for the remainder of the century. Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction (Tyler, 1949) challenged the educational community with four questions that each school should ask:

- What educational purposes should the school seek to attain?

- What educational experiences can the school provide to attain these purposes?

- How can these educational experiences be effectively organized?

- How can we determine if these purposes are being attained?

One can see the foundation of the Big Four in Tyler's questions, but keep in mind that in Tyler's time, the goal was to improve the school because it was assumed that as schools improved, so would student achievement. We find out later that, in fact, improving schools and structures does not necessarily improve learning for all students.

Curriculum Objectives for Educational Experiences

The post-World War II baby boom led to significant growth in the school-age population and also a call for new ways to design assessments based on the significant research gleaned from testing soldiers on specific criteria or standards for success. These ideas were consistent with Tyler's four questions to ensure successful schools.

The document, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, was developed by 34 university assessment professors, edited by Benjamin Bloom, and in fact dedicated to Ralph...