![]()

Chapter 1

Feedback: An Overview

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Feedback says to a student, "Somebody cared enough about my work to read it and think about it!" Most teachers want to be that "somebody." Feedback matches specific descriptions and suggestions with a particular student's work. It is just-in-time, just-for-me information delivered when and where it can do the most good.

This book is intended to help teachers provide such feedback to students. The focus is on feedback that comes from a teacher to a student and is based on student work. In the context of the book, the term feedback means "teacher feedback on student schoolwork." Important as they are, responses to student behavior are not considered here.

Feedback as Part of Formative Assessment

Feedback is an important component of the formative assessment process. Formative assessment gives information to teachers and students about how students are doing relative to classroom learning goals. From the student's point of view, the formative assessment "script" reads like this: "What knowledge or skills do I aim to develop? How close am I now? What do I need to do next?" Giving good feedback is one of the skills teachers need to master as part of good formative assessment. Other formative assessment skills include having clear learning targets, crafting clear lessons and assignments that communicate those targets to students, and—usually after giving good feedback—helping students learn how to formulate new goals for themselves and action plans that will lead to achievement of those goals.

Feedback can be very powerful if done well. The power of formative feedback lies in its double-barreled approach, addressing both cognitive and motivational factors at the same time. Good feedback gives students information they need so they can understand where they are in their learning and what to do next—the cognitive factor. Once they feel they understand what to do and why, most students develop a feeling that they have control over their own learning—the motivational factor.

Good feedback contains information that students can use, which means that students have to be able to hear and understand it. Students can't hear something that's beyond their comprehension; nor can they hear something if they are not listening or feel like it would be useless to listen. Because students' feelings of control and self-efficacy are involved, even well-intentioned feedback can be very destructive ("See? I knew I was stupid!"). The research on feedback shows its Jekyll-and-Hyde character. Not all studies about feedback show positive effects. The nature of the feedback and the context in which it is given matter a great deal.

Feedback as Part of the Formative Learning Cycle

This second edition of How to Give Effective Feedback to Your Students is expanded from the first edition in several ways, all of which have to do with placing feedback in the context of the formative learning cycle. In the years since the first edition, I have come to realize more deeply the role of feedback in the regulation of learning and the formative learning cycle (Andrade & Brookhart, in press; Moss & Brookhart, 2015). We will explore these ideas further in future chapters. For now, the important point is that feedback should be part of a learning process. Even the most elegantly phrased feedback message will not improve learning unless both the teacher and student learn from the feedback process and unless the student has, and takes advantage of, an opportunity to use the feedback. This second edition adds information about both of those parts of the process and therefore presents a more complete picture of feedback in the context of classroom learning.

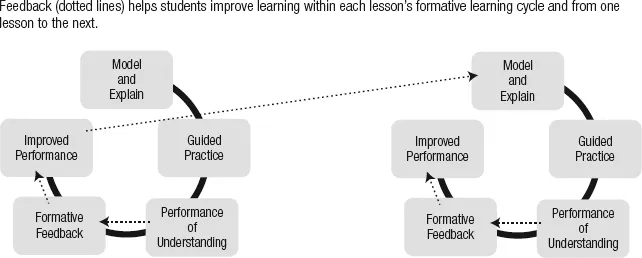

Briefly, you can think of the formative learning cycle as the structure within a lesson that allows students to experience the three formative assessment questions (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Sadler, 1989): Where am I going? Where am I now? and How do I close the gap? (sometimes written "Where to next?"). The most effective learning occurs when students know what it is they are trying to learn, use criteria to actively compare their current work to the goal, and take action to improve (Moss & Brookhart, 2012). Formative feedback is part of this process. It is not giving comments on final work at the end of the lesson. There is no ongoing learning process there; the work either goes home or gets thrown away, and the student may or may not remember the comments the next time she does similar work. Formative feedback involves giving comments (or arranging for self- or peer assessment), then giving a student additional performance opportunities within the same learning cycle. Even feedback that occurs on that additional work should feed students forward to the learning that comes next, usually the next lesson's learning target. Figure 1.1 describes this process in diagram form.

Figure 1.1. Feedback Feeds Forward: Feedback and the Formative Learning Cycle

Source: Adapted from Learning Targets: Helping Students Aim for Understanding in Today's Lesson (p. 22), by C. M. Moss and S. M. Brookhart, 2012, Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

The "Three Lenses"

This book will use the metaphor of "three lenses"—a microscope lens, a camera lens, and a telescope lens—to describe how to give effective feedback that students can use in the formative learning cycle. In the years since the first edition, I have done a lot of professional development on the topic of feedback, and I have found that thinking in terms of these three lenses is helpful. The "micro view" means looking at the feedback message itself, as if through a microscope, analyzing what is said or written and how the message is delivered. The "snapshot view" means looking at the feedback as an episode of learning, as if a camera were taking a snapshot of the learning. In the snapshot view, we ask two questions: What did the teacher learn from the feedback episode, and what did the student learn from it? The "long view" means looking at the results of the feedback, as if looking through a telescope into the distance. Did students have an opportunity to use the feedback, did that in fact occur, and did learning improve?

Figure 1.2 presents a Feedback Analysis Guide that I often use to help teachers focus on the three lenses and to emphasize that the quality of feedback rests on synthesizing what's learned from the three perspectives, not just the feedback message itself.

Figure 1.2. Feedback Analysis Guide

Micro view

Evaluate the feedback.

- Is it descriptive?

- Is it timely?

- Does it contain the right amount of information?

- Does it compare the work to criteria?

- Does it focus on the work?

- Does it focus on the process?

- Is it positive?

- Is it clear (to the student)?

- Is it specific (but not too specific)?

- Does its tone imply the student is an active learner?

Snapshot view

What evidence of learning does the feedback provide?

What did the student learn from it?

What did the teacher learn from it?

Long view

What next step(s) should the teacher and student take to use this feedback for learning? How were these steps taken? Did learning improve?

To see Figure 1.2 as an image, please click here.

Feedback and Grading

Although this book focuses on formative feedback, it is worth noting that feedback has traditionally occurred (and continues to, in some quarters) as part of grading—that is, summative assessment. This section gives an overview of issues related to feedback and grading that I hope will help explain my focus on formative feedback.

Going back 50 years, several studies have investigated the effects of grades versus comments on student performance. In one classic study, Page (1958) found that student achievement was higher for a group receiving prespecified comments instead of letter grades and higher still for students receiving free comments written by the teacher. Writing comments was more effective for learning than giving grades. Other researchers have replicated Page's study many times over the years, with some replicating the results and others not (Stewart & White, 1976). More recent research has identified the problem: in the earliest studies, the "feedback" provided was evaluative or judgmental rather than descriptive. Page himself described the prespecified comments as words that were "thought to be 'encouraging'" (1958, p. 180). Evaluative feedback is not always helpful.

The nature of "comment studies" changed as the literature on motivation began to point to the importance of the functional significance of feedback—that is, whether the student experiences the comment as information or as judgment. Butler and Nisan (1986) investigated the effects of grades (evaluative), comments (descriptive), or no feedback on both learning and motivation. They used two different tasks—one quantitative task and one divergent-thinking task. Students who received descriptive comments as feedback on their first session's work performed better on both tasks in the final session and reported feeling more motivated about their work. Students who received evaluative grades as feedback on their first session's work performed well on the quantitative task in the final session but poorly on the divergent-thinking task and were less motivated. The students who received no feedback performed poorly on both tasks in the final session and also were less motivated.

Butler and Nisan's experiment illustrates several of the aspects of feedback discussed in this book. First, the comments that were successful were about the task. Second, they were descriptive. Third, they affected both performance and motivation, thus demonstrating what I call the "double-barreled" effect of formative feedback. And fourth, they fostered interest in the learning for its own sake, an orientation found in successful, self-regulated learners. Butler and Nisan's work affirms an observation that many classroom teachers have made about their students: if a paper is returned with both a grade and a comment, many students will pay attention to the grade and ignore the comment. The grade "trumps" the comment; the student will read a comment that the teacher intended to be descriptive as an explanation of the grade. Descriptive comments have the best chance of being read as descriptive if they are not accompanied by a grade.

Looking Ahead

This book is organized according to the three lenses described earlier. For each lens, I present some relevant research and then describe how to apply the lessons of the research in practice.

Chapters 2, 3, and 4 are about the content of the feedback message itself—the "micro view." Conclusions drawn from literature reviews on studies of feedback inform the practical checklist in the upper left portion of Figure 1.2.

Chapter 5 is about viewing feedback as an episode of learning—the "snapshot view"—and cites literature from some current studies of formative assessment. What is emerging from this literature—which admittedly is still in its infancy—is that teachers who respond to what students are thinking are more effective at formative assessment than those who respond to how many correct answers students get. This finding has huge implications for feedback. In Chapter 5, I suggest ways to look at student work for evidence of student thinking and how to connect that to feedback messages about where students are and what they should do next. The upper right portion of Figure 1.2 reminds us to analyze feedback episodes by describing what both the teacher and the student learned. Teachers should learn how students are thinking about the learning target or goal they are pursuing. Students, of course, should learn where they are in their learning and what to do next.

Chapter 6 is about helping students use feedback—the "long view"—and cites reviews of studies of the regulation of learning and studies of self- and peer assessment. Practical implications of the findings from these studies for instructional planning include arranging activities where students analyze and use their feedback, alone or with peers, and produce evidence that the feedback resulted in learning. To close the loop, teachers can give students feedback on that very point, making sure they know that their thoughtful use of feedback led to better work—giving what Hattie and Timperley (2007) would call feedback about the processing of the task and about self-regulation. The lower panel (the "long view" portion) of Figure 1.2 reminds us to build opportunities for students to use feedback into instructional planning, and to check that learning does in fact occur.

Finally, Chapters 7 and 8 address two important topics that cut across the three lenses. Principles of effective feedback apply to both simple and complex assignments and to all subjects and grade levels. Effective feedback takes into account both what the student was supposed to be learning and who the learner is. Chapter 7 gives more examples of feedback in English language arts and mathematics at different grade levels, to broaden the example pool and help readers transfer principles of effective feedback to their own teaching context. Chapter 8 discusses differentiating feedback for learners.

![]()

Chapter 2

Feedback: The Micro View—Characteristics of the Feedback Message

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Effective feedback is part of a classroom assessment environment in which students see constructive criticism as a good thing and understand that learning cannot occur without practice. If part of the classroom culture is to always "get things right," then if something needs improvement, it's "wrong." If, instead, the classroom culture values finding and using suggestions for improvement, students will be able to use feedback, plan and execute steps for improvement, and, in the long run, reach further than they could if they were stuck with assignments on which they could already get an A without any new learning. It is not fair to students to present them with feedback but no opportunities to use it. Nor is it fair to present students with what seems like constructive criticism and then use it against them in a grade or final evaluation.

What the Research Shows

The first studies and theories about feedback are more than 100 ...