![]()

Chapter 1

Why Evaluation Matters

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Snapshot:

This chapter describes challenges facing school districts when evaluating instructional coaches and coaching programs. It outlines the book's approach to evaluation and the thinking behind it. You can skip this chapter if you already know you need changes in your evaluation system and want specifics on how to do that.

Standards. Assessment. Evaluation. Accountability. As a high school teacher and instructional coach, Malikah has applied these terms to both students and herself many times over.

As a teacher, she welcomed the Standards Movement of the 1990s in her early teaching years to address content accountability. After all, was it really such a stretch that teachers and schools should have some way to specify which concepts students should learn in which grades? In Malikah's student teaching experience, when she was given free rein to teach whatever she wanted to ninth graders, she wished she had more guidance. "Have they already learned the parts of a sentence? A paragraph? An essay? Have they read Shakespeare before? How do we know?" The Standards Movement promised to answer the fundamental questions of "What should they know?" and "What do they know?" and allowed states to tailor standards and their assessments to their own needs and priorities. Malikah had faith that her state would work it out.

When the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, 2001) came along, she thought that made sense, too. For too long, the inconsistent quality of public education from state to state and district to district (and the extraordinary equity issues that ensued) had alarmed educators and frustrated families. National oversight made sense. Consequences for poor performance made sense. Malikah had faith that the federal government would work it out.

Later, when NCLB's approach to school improvement exposed problems in the notion of punishing schools who most need support, the federal Race to the Top (U.S. Department of Education, 2009) competitive grant program entered the fray. Variations in the rigorousness of state standards and testing programs under NCLB had everyone wondering whose state programs were best: "How do our kids really stack up? Are we assessing the right things?" The idea of consistency across states made sense. This time, the rules promised less punishment and more support when students performed poorly. They also promised more individual teacher accountability for school improvement and more fairness, relevance, and specificity in teacher evaluation. Although Malikah had less faith that the government would work it out after what happened with NCLB, still she hoped for the best.

While waiting to see what would happen with national student assessment under Race to the Top, school districts had time to focus on how they would change teacher evaluation. Like so many districts nationwide, Malikah's district decided to use Charlotte Danielson's Enhancing Professional Practice: A Framework for Teaching (2007) to design its teacher evaluation system. Yet, her district's version of that framework bore little resemblance to anyone else's because Danielson's work was interpreted in so many different ways across districts nationwide. In fact, sometimes interpretations varied so widely that what made a teacher "needing improvement" in Malikah's district was considered "effective" for a teacher in the next county over.

In Malikah's district, the planning and instruction items from the previous teacher evaluation form now constituted 50% of her overall evaluation, whereas whole-school improvement data and data targets she set for her own students comprised the other half. Every year, the way those data points were calculated changed. Every year, teachers felt that none of those data points accurately assessed their teaching (positively or negatively). Every year, "fairness" seemed elusive. "Accountability" seemed to refer "only to what teachers are doing wrong," not the good work they were doing every day.

When the new national student assessments were released, they, too, were disappointing. They were not as closely aligned to the standards as teachers had expected, and the ways that questions were structured seemed to run counter to research on testing validity and reliability. As a result, many states left the newly established testing consortia and reverted back to their own state tests. Malikah, who had never been allowed to voluntarily exit unfair assessments of her own work, wondered, "States can do that? So what then is a truly good assessment of learning?" Fairness and accountability seemed elusive for students as well.

Amid all of this confusion and inconsistency, amid all of the good intentions and missteps, Malikah and her fellow teachers showed up to school every day and did the best job they could. Knowing that their work would be misunderstood and often inadequately evaluated, they taught their students anyway.

But the previous 20 years did take their toll. Malikah has less confidence in new assessment paradigms for students and for teachers. With every new attempt to improve an evaluation system, she shrugs her shoulders and wonders, "What is it this time?" Malikah has always been a positive force in schools, but even she has become jaded on the subject of evaluation and accountability.

A few years ago, Malikah left the classroom and decided to become an instructional coach. She wants to support teachers through this uncertain maze of school reform. She wants reform to work for teachers—and especially for students—as much as humanly possible. She wants students to get what they need to have the lives they want, and she knows that teachers want that, too. What she didn't know was that her evaluation as an instructional coach in her building (and indeed the whole coaching program in her school district) had no more clarity, alignment, or validity than student or teacher evaluation did. When her principal explained to her that, "Well, we don't have a specific form to evaluate coaches, so we'll just tweak the teacher form a little, OK? We'll figure it out," Malikah's first thought was, "Here we go again."

Where We Are

Accountability is a need in any given school system. Any organization that involves the education, care, and support of children should be held to high standards regarding how those services are delivered. Approximately 80% of school budgets are spent on staffing (National Center for Education Statistics, 2021), so schools must be accountable to taxpayers, school boards, parents, community members and, most important, students. Measuring effectiveness is not possible without continually reflecting on practice and evaluating how practice aligns with actual progress on student outcomes.

We can't begin to count how many times we've been asked by school and school system leaders for help in evaluating the good work their coaches are doing in classrooms. Even though these leaders are beholden to laws and policies regarding employee evaluation, few evaluation systems are specifically geared toward coaching roles. School leaders have an additional layer of accountability with regard to coaching positions because coaches often are released from all classroom teaching duties, and leaders, therefore, must provide justification for these roles. To deal with this issue, some districts use a catch-all evaluation form for "teachers on special assignment" (TOSAs), even though those TOSA roles are often extremely varied and may bear no resemblance to each other. Others take an existing teacher evaluation system and try to modify it to work for coaches, which is about as effective as evaluating how well an apple is performing as an orange, yet that is the most common "coaching evaluation" process we see in schools. Clearly, that process is not helpful to leaders, coaches, or the school itself.

In addition to lacking a clear and helpful process for evaluating coaching positions, school leaders often tell us that no formal evaluation process for overall coaching programs is in place either, a deep concern in an era of near-constant education budget debates. No data on coaching program impact means that coaching programs are constantly on the budgetary chopping block, and cutting coaching positions does not help teachers or students to improve.

From a whole-school perspective, without specific metrics specifying the quality of a program implementation in a targeted area, appropriate evaluation to help guide improvement efforts is extremely challenging. That is, lack of specificity about how the implementation is going makes helpful conversations about improvements or next steps among administrators, coaches, and teachers nearly impossible. Not surprisingly, many reform efforts involve false or exaggerated claims of success (Guskey, 2000). Ensuring that schools and school districts have accurate information about both coaches and coaching programs is crucial to guide both improvement in supporting classrooms and ensuring accountability.

When evaluation processes work best, employees can use that process to set goals for improvement in their work. With sound practices in place to evaluate instructional coaches and coaching programs, instructional coaches will get better in their work, and that means teachers will get better in their work and, ultimately, that students will learn more.

On the other hand, when evaluation processes are not clear or aligned to a set of standards, employees sometimes "check out" because they don't feel seen or appreciated by their supervisors. Malikah learned long ago that her observations and evaluations were merely hurdles to navigate each year, not conversations about her ambitions for her own growth or that of her students. After many years of participating in evaluations that she knew would not substantially change anything, during post-observation conferences, she would smile, nod her head, sign the form, and then head to lunch. Poor evaluation tools that merely go through the motions and "check boxes" unintentionally discourage employees and make setting improvement goals difficult.

Too often, evaluation is viewed as a bookkeeping task that leaders must monitor and not as an improvement process for supporting employees. The uncomfortable nature of one adult telling another adult "how you're doing" at work leads many leaders to want to make the interaction as brief and as mild as possible, regardless of what's happening with the employee.

Jim recalls a principal once explaining his litmus test for successful evaluation conferences: "If the teacher doesn't cry or get angry, then I feel it's a good evaluation." Michelle once worked for a principal who told her that the basis for how positive or negative his teacher evaluations are is whether parents had called to complain. These are very low bars and ones that discourage honest conversations about performance and improvement. When both the evaluator and the employee end the evaluation process primarily feeling relief that it's over, there's a problem.

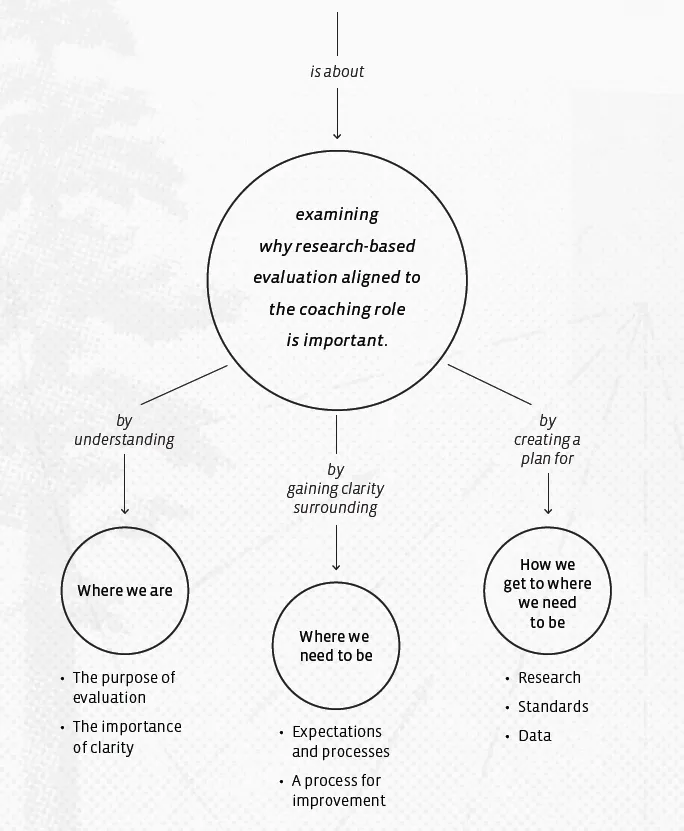

To advocate for change in the evaluation of coaching and coaching programs, this chapter

- » examines the purposes of evaluation processes,

- » reinforces the importance of clarity around every facet of job performance,

- » gives an overview of expectations and processes that are key to fostering an evaluation as a process for improvement, and

- » describes some of the research guiding the development of our evaluation rubrics.

The Purpose of Evaluation

Periodic evaluations for employees in any job can be useful. According to the Society for Human Resources Management (SHRM; Fleischer, 2018), reasons to evaluate include "providing a rational basis on which to promote, discipline, and terminate" (p. 42). SHRM also advocates for the important evidence that periodic evaluations can provide to ensure that any "adverse actions" that an employer takes involving an employee are not discriminatory or improper, and cites new employees as finding evaluations particularly helpful as they learn the job (p. 42). SHRM cautions, though, that when evaluations do not follow best practices, evaluations can "do more harm than good" (p. 42).

The idea of evaluation itself is not the villain. Evaluation problems can arise from any of several sources:

- » evaluators not using data reliably to inform the evaluation (for coaches, this connects to issues surrounding data not directly tied to coaching, as we discuss in chapter 2),

- » employees not having a clear picture of reality about their performance (for coaches, this connects directly to issues surrounding role clarity, as we discuss in chapters 2 and 4),

- » the defensive response that most professionals have to feedback and advice (for coaches, this connects to the way supervisors often handle coaches' evaluation conversations, as we discuss in chapters 2 and 4), and

- » the tendency of some evaluation tools to oversimplify the complexities of the job (for coaches, the issue of using another role's evaluation form or process looms large here, as we discuss in chapter 2).

Few employees push back on the idea of receiving an evaluation and feedback on their work. It's the way that leaders handle evaluation that employees typically find troubling, especially when they feel that evaluation processes are not aligned with the job they've been asked to do or are not fairly and equitably managed from employee to employee. Instructional coaches are widely perceived as positive and enthusiastic employees, but they, too, understandably push back against evaluations that they view as unfair or inconsistent. Ensuring a clear focus on what the purpose of a particular evaluation is critical as a starting point to ensure not only that evaluation involves accountability for the organization but also fairness and helpfulness for the employee.

For instructional coaches, sound periodic evaluation has several benefits.

Sound evaluation

- ensures that the right people are in the right roles,

- helps leaders to identify (and, therefore, provide) appropriate training and resources for coaches,

- ensures alignment of what coaches do with the goals of the school or district by adhering to standards of best coaching practice,

- assists administrators in providing the most useful feedback to coaches on their performance by aligning with standards of best coaching practice, and

- assists coaches in highlighting successes and targeting the best goals for improvement.

For instructional coaching programs, sound periodic evaluation can support the improvement of the organization as a whole (whether school- or district-based). Evaluating coaching programs fosters

Sound Evaluation Checklist

Sound Evaluation …

____ Ensures that the right people are in the right roles

____ Helps leaders to i...