![]()

Section III

The Nuts and Bolts of Choice

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Now, in this final section of the book, it's time to roll up our sleeves and think about how to actually facilitate choice well. For although there is a wide variety of kinds of choice, many of which are quite simple (e.g., choosing between two worksheets; choosing to either work alone or with a partner), there's no getting around the fact that using choice with students makes things more complex. Of course, it's always nearly worth it, but only if it's done well, for choices that aren't matched to students' needs, or choices that get out of control and veer away from learning goals, won't have the benefits you're seeking.

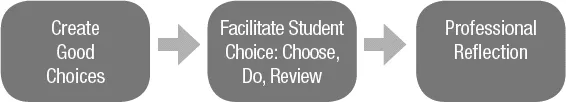

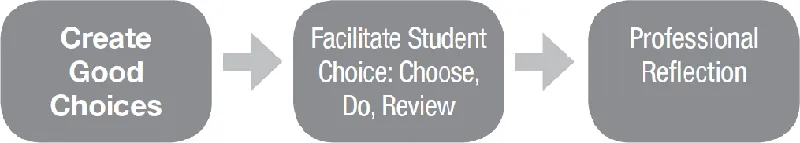

Section III will help you explore the three-part process teachers should use to implement choice, which also includes the three-part process students should experience as a part of a complete choice experience.

Student Process

There are typically three stages of any good learning experience. Learners first think ahead about the work they are about to do, then they do the work, and then they think back about the work they just did. This tried and true "before-during-after" structure is a simple and effective process. A familiar example of this can be found in the reading and writing workshop approach to literacy instruction. Typically, each class begins with a mini-lesson that helps orient students to the skills and objectives of the day and provides some clear and concise direct instruction. Next, students read, write, confer, meet in a group, or engage in other rich literacy experiences. The period wraps up with a time for sharing and reflecting to help students consolidate learning.

A six-week unit in which groups of students study different topics and create different projects will involve much more time choosing than will a simple two-choice practice session involving vocabulary words. However, this basic structure will offer a starting place for your plans, regardless of whether you are using choice during a homework assignment, to structure learning on a field trip, to help students practice a skill, or to assess student learning at the end of a unit. There are a wide variety of terms used for this class three-part plan. Two common sets are opening-body-closing and initiation-work period-consolidation. In this book I use the terminology of choose-do-review, and each stage is discussed in-depth in Chapters 6–8.

Choose

During this first stage, teachers set students up to make good choices. They explain what the choices are so students can make informed decisions. Teachers provide both time and structures to help students make thoughtful choices.

Do

Once students have made their choice, they follow through and engage in the work at hand. Teachers serve as coaches, helping students as needed—guiding, supporting, troubleshooting, and encouraging—so students can be successful with their learning.

Review

Teachers provide students the chance to think back about what they learned, how they worked, and how their choice supported (or didn't support) their learning. This both helps drive home the learning and helps students develop skills of self-reflection that enable them to become more skilled at making effective choices in the future.

Teacher Process

Just as there is a three-part structure you use to plan choice for students, so too, there is a three-part process in which you engage as a teacher planning and implementing choice. Chapter 5 will help you think about the first step of the teacher process, how to create choices that are meaningful for students—ones that directly connect with learning goals as well as students' needs and preferences. In Chapters 6, 7, and 8, you will learn how to facilitate choice well for students. You'll explore how to help students make good choices, support them as they work, and finally, help them review their choices and learning to deepen their abilities of self-reflection and effective decision making. Chapter 9 is a brief chapter that will help you complete the teacher planning process—reflecting on the choice experience so that you can grow in your implementation of choice.

![]()

Chapter 5

Creating Good Choices

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Christine stands in front of the class, her eyes beaming with pride. Students in my 4th grade class have spent the last week creating projects to share what they have learned about the solar system. Christine has studied the sun. She has collected many interesting facts, organized them into categories, and worked hard on her project, and she is excited to share it with the class. I have been impressed with her efforts, for Christine is a student who sometimes struggles with following through on a plan and often doesn't put a lot of energy into schoolwork. This project, however, is different. She has been so enthusiastic about the idea of painting a giant sun costume and has poured so much time and effort into her work, meticulously constructing a sun (no small feat for 4th grade fingers that tire quickly using scissors to cut through rigid cardboard) and then painting every square inch of it in various shades of yellow and orange, that neither of us has considered whether or not a giant sun costume is a good choice for her content.

Christine's presentation falls flat. She is justifiably proud of her sun costume, but she doesn't have much to say. She stammers through an explanation of her costume and how hard she has worked on it, looks nervously down at her notes and shares some of the facts she had learned, takes a few questions from her classmates, and sits back down.

I'm not sure that Christine fully understood what happened that day, but I learned a valuable lesson: Choice as a strategy is only effective if the choices themselves are good ones. That is the focus of this chapter—creating good choices. After all, although choice is an amazing strategy that can fit many different situations in any grade or content area, here's another important time to remember that choice is a means to an end, not an end in and of itself. Choice should only be used if it will enhance student learning, either by helping students engage in work that is appropriately challenging or by boosting motivation by tapping into strengths, interests, or needs. A teacher I once worked with aptly stated: "Four bad choices are worse than none at all." Poor choices can discourage learners, waste time, and dampen enthusiasm for learning. There are many times when choice is not an appropriate strategy, so do not force it when it's not a good fit. When it is a good fit, make sure to create options that will enhance student learning.

So, what exactly are good choices? How do you know whether options are good ones or not? Especially if using choice as a strategy in daily learning is something new, it can feel overwhelming. Where do you start? This chapter covers the key characteristics of choices that will enhance learning. Through considering each of these characteristics, teachers can create options for students that will make the highest potential impact on their work.

Choices Should Match Learning Goals

Christine's sun project wasn't a good fit because painting a giant cardboard cutout of the sun did nothing to reinforce or help share content she was supposed to learn. She was highly engaged, but the engagement wasn't connected with the learning goals, so it didn't pay any real dividends on learning science content. This is perhaps the most important characteristic of good choices—they must match students' learning goals. Consider the two following sources for student goals: (1) standards, content, and curricula and (2) process goals.

Standards, Content, Curricula

When thinking of possible choices for students, begin with the academic content goals. What are students supposed to be learning? If you're not crystal clear about this, your choices may not end up being a good fit. For example, as a first-year teacher, I remember asking a colleague what our first science unit was. "Prairie dogs," she answered. "Prairie dogs? Why prairie dogs?" I remember replying. As it turns out, the first chapter in the science textbook was all about prairie dogs—as a way of helping students learn about animals that live in communities. Though prairie dogs may be cute, I wasn't sure this topic was going to resonate with all of my students. Once I understood the true goal of the science unit, I was able to structure choices that gave students more control over some of the content (which animals to study) while meeting the important learning goals of the unit (understanding the characteristics of animals that live in communities). Small teams of students chose animals they were interested in that lived in communities, and each team had to learn the key content outlined in the science text (different roles in the group, social hierarchy, etc.). Students were engaged, were energized, and learned a lot about all of the important scientific ideas in the unit. The five groups chose to study ants, dolphins, lions, wolves, and killer whales. No one chose prairie dogs.

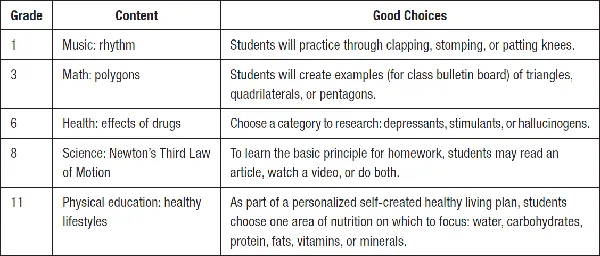

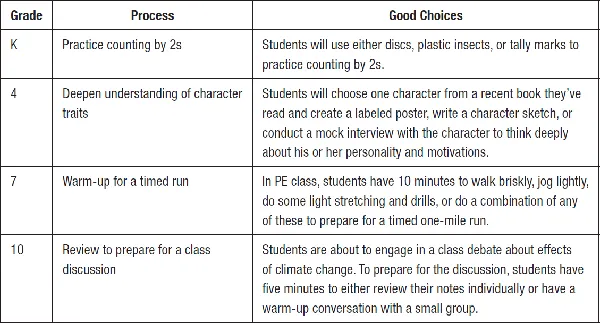

One time when I was working with a group of high school teachers, a drama teacher wondered if choice might help with an upcoming project. His students were about to create their own version of Hamlet. Their work needed to be inspired by the Shakespearean original but also needed to have its own flavor and some original twists. One of the challenges of the project was the initial intake of the play—all students needed to understand the story in order to participate in the adaptation. As a bit of a purist, his default was to require all students to read the original play. This was problematic because even though all students were competent readers, the original text was a bit too complex for some. He also knew that some students had really heavy course loads and many after-school commitments; because the reading had to be done outside of class, he wasn't sure how thoroughly all students read the text, which then limited their participation in the rewrite. I asked him if he had any different versions of the play, and as it turned out, in addition to the original, he also had an annotated edition. He decided to make both available and allow students to choose the one they thought was the best fit for them—both in terms of comprehension and time. This was a great fit because each choice allowed students to read the play and be prepared to move forward with the class project. Figure 5.1 highlights some other examples of choices that are a good match for the content.

5.1 Choices That Match Content Goals

Process Goals

Of course, content is rarely, if ever, separate from process, so in addition to considering choices that match what students are learning, you should also consider how and to what degree they are learning. Are students practicing a skill or trying to memorize content? If so, choices should likely involve practice and repetition. Are students preparing for a class discussion? If so, each option should probably require note taking of some kind to help students record their thinking. This was one of the problems with Christine's sun project—the process of coloring the sun didn't match the learning goals of deepening understanding and preparing to share learning. I remember making a similar mistake once in a math class. After teaching a lesson on reducing fractions, I gave students a few choices for how to practice: They could complete problems in their workbook, create their own problems to practice, or draw a visual representation of reducing fractions. Through this third choice, I was trying to reach out to students who learn visually and might get excited about using colored pencils or markers to draw fractions. The problem was that drawing pictures of fractions takes a while. Students who chose to work in the workbook or create their own problems got a lot of repetition. The students who chose to draw only had time for a few and didn't get much practice—that choice matched the content goal but not the process one.

Here's an example of a choice that matched both content and process. Nate Grove's 8th grade social studies class at Oyster River Middle School in Durham, New Hampshire, had spent weeks analyzing the causes of the American Revolution as they explored the essential question, "Was the American Revolution reasonable?" As a final assessment, each student would formulate an argument (defined as "a civil exchange of reasonable ideas in order to better be able to understand the truth") about whether or not the war was reasonable. In previous years, Nate's students had all written a position paper, but he suspected that some didn't put forth as much effort as they could, thereby limiting how well he could assess their knowledge and understanding. So this year, in addition to getting a problem or example choice (choosing three of eight given events or ideas), students also had a project choice:

- Art. Create a side-by-side piece that clearly lays out both sides of the argument and allows the viewer to understand the position you are taking. You must include a written artist statement explaining your choice of images and how they support your position.

- Museum-style curation. Create a display of three-dimensional artifacts that clearly explains both sides of the argument and allows the viewer to understand the position you are taking. Your museum pieces must include placards explaining why you created the artifacts and how they support your position.

- Position paper. Write a paper that considers three of the events from both points of view and takes a position regarding the central question ("Was the Revolution reasonable?"). Use specific and relevant evidence and examples.

Students had one class period to consider their choices and begin to sketch their initial plans and then three more class periods to complete their work. Upon reflecting on this experience, Nate was convinced that overall students worked harder than they had in previous years. Importantly, all three of these options also allowed Nate to gain a deep understanding of students' knowledge and understanding of the American Revolution, as well as their abilities to craft an effective position statement. Figure 5.2 highlights some other examples of choices that are a good match for the process goals.

5.2 Choices That Match Process Goals

Choices Should Match Students

In addition to matching curricular goals, good choices should also be a good fit for students. Consider possible choices from the perspective of your learners. In whatever lesson, unit, or activity you are planning, imagine yourself as a student in your class. What is already appealing, and what might be a turn-off? What might be easy or hard? How might choice help make things better? Chapter 2 explored how building relationships with students can help students develop a sense of trust that will allow them to take risks. Now we see another important benefit of getting to know students well: You can then create choices that flow directly out of your knowledge of their interests, strengths, needs, and experiences.

Choices Should Reflect Students' Interests and Strengths

It is the end of the school year, and my students are going to engage in one final research project. Because there isn't one unifying theme, topics are varied and diverse. Still, I am a bit surprised and skeptical when Justin announces his first choice of topics: the human arm. "Not the hand or the shoulder, Mr. A.—from here to here," he states, making chopping motions at his wrist and shoulder. I am inclined to steer Justin in a different direction, but first I ask, "Why the human arm?" He goes on to talk with surprising excitement and animation about questions he has about how the bones and muscles fit together and what makes it all work together. He even already has ideas for projects he might take on, both to learn and to share his learning. Seeing his passion for the topic, and knowing that some of the interest is likely the result of having a father who is a physical therapist, I decide to let him go with it, and it turns out to be an amazing research project. During his 20-minute presentation to the class, he has students feeling their own arms to identify different bones and muscles. He builds a simple model of the human arm out of wood and elastic bands to demonstrate how one set of muscles tightens as the other relaxes. I am amazed at how much there was to know about the human arm.

This is perhaps a bit of an extreme example, but it makes the point. When you know your students' interests and passions—when you understand what makes them tick—you can ...