![]()

Chapter 1

Understanding Differentiated Instruction: Building a Foundation for Leadership

Look inside almost any classroom today and you'll see a mirror of our country. You'll find students from multiple cultures, some of whom are trying to bridge the languages and behaviors of two worlds. Students with very advanced learning skills sit next to students who struggle mightily with one or more school subjects. Children with vast reservoirs of background experience share space with peers whose world is circumscribed by the few blocks of their neighborhood. All these students have the right to expect enthusiastic teachers who are ready to meet the students as they are, and to move them along the pathway of learning as far as fast as possible.

The reality, however, is that many of these students will encounter a teacher who is enmeshed in a system geared up to treat all 1st graders as though they were essentially the same, or all Algebra I students as though they were alike. Classrooms and schools are rarely organized to respond well to variations in student readiness, interest, or learning profile (Archambault et al., 1993; Bateman, 1993; International Institute for Advocacy for School Children, 1993; McIntosh, Vaughn, Schumm, Haager, & Lee, 1993; Tomlinson, 1995; Tomlinson, Moon, & Callahan, 1998; Westberg, Archambault, Dobyns, & a and b; Salvin, 1993). Most educators appear even to lack images of how a classroom might look—how we would “do school”—if our intent was to respond to individual learner needs. In fact, the challenge of addressing academic diversity in today's complex classrooms is as important and difficult a challenge as we have before us.

We've learned a great deal recently about how applying “differentiated instruction” can help address the needs of academically diverse learners in our increasingly diverse classrooms (see Chapter 2 for a discussion of the theory and research that supports differentiation as a way of thinking about teaching and learning). Many teachers have begun to use, or expanded their use of, the principles and practices of differentiation. To make these practices more widespread—to move from differentiation in individual classrooms to differentiation that is pervasive throughout schools and school districts—requires strong and skilled leadership.

As logical as such personalized classrooms seem, making them a reality challenges many comfortable assumptions and practices related to teaching and learning. For instance, planning for more personalized classrooms prompts an array of questions: Do our current practices make learners more independent or more dependent? What is the purpose of “standard” report cards, and are they effective? Does learning happen in someone or to them? How can we be “fair” and still respond to learner variance? How do standards and standardization differ?

We might be tempted to just cast aside, or try to forget, these sorts of professional goblins; changing practices in response to prickly insights can be troublesome. Until we face these questions, though, most students inside the classroom door will be ill served. Without large numbers of classrooms where teachers are skilled in meeting varied learners where they are and moving them ahead briskly and with understanding, the number of frustrated and disenfranchised learners in our schools can only multiply.

The purpose of this chapter is not to present an exhaustive discussion of differentiated instruction. (See the list at the end of the chapter for resources on this topic.) Rather, the chapter first reviews key vocabulary and principles of effective differentiation. The chapter then addresses some fundamental questions about differentiation that are important for people who want to establish a greater number of responsive or differentiated classrooms in their districts or schools.

Key Vocabulary and Principles of Effective Differentiation

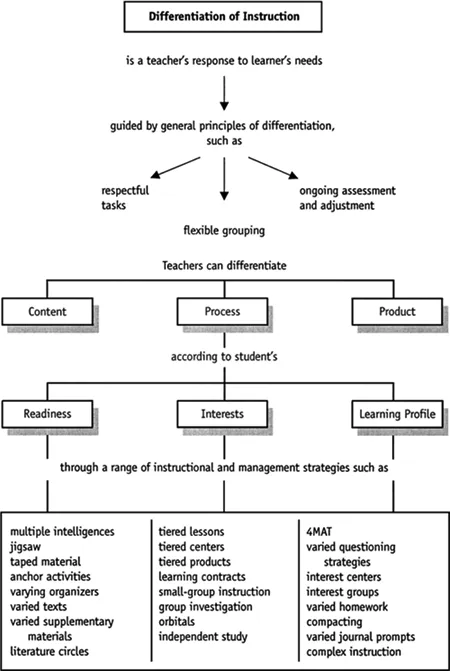

Teachers can create differentiated, personalized, or responsive classrooms in a number of ways. Figure 1.1 presents a concept map for thinking about and planning for effectively differentiated classrooms.

Figure 1.1. A Concept Map for Differentiating Instruction

A Definition of Differentiation

In the context of education, we define differentiation as a teacher's reacting responsively to a learner's needs. A teacher who is differentiating understands a student's needs to express humor, or work with a group, or have additional teaching on a particular skill, or delve more deeply into a particular topic, or have guided help with a reading passage—and the teacher responds actively and positively to that need. Differentiation is simply attending to the learning needs of a particular student or small group of students rather than the more typical pattern of teaching the class as though all individuals in it were basically alike.

The goal of a differentiated classroom is maximum student growth and individual success. As schools now exist, our goal is often to bring everyone to “grade level” or to ensure that everyone masters a prescribed set of skills in a specified length of time. We then measure everyone's progress only against a predetermined standard. Such a goal is sometimes appropriate, and understanding where a child's learning is relative to a benchmark can be useful. However, when an entire class moves forward to study new skills and concepts without any individual adjustments in time or support, some students are doomed to fail. Similarly, classrooms typically contain some students who can demonstrate mastery of grade-level skills and material to be understood before the school year begins—or who could do so in a fraction of the time we would spend “teaching” them. These learners often receive an A, but that mark is more an acknowledgment of their advanced starting point relative to grade-level expectations than a reflection of serious personal growth. In a differentiated classroom, the teacher uses grade-level benchmarks as one tool for charting a child's learning path. However, the teacher also carefully charts individual growth. Personal success is measured, at least in part, on individual growth from the learner's starting point—whatever that might be. Put another way, success and personal growth are positively correlated.

The remainder of Figure 1.1 expands on our definition of differentiation, providing a handy framework for thinking about, planning for, and evaluating the success of differentiation.

Principles That Govern Effective Differentiation

As Figure 1.1 suggests, some key principles guide differentiation. Understanding and adhering to these principles facilitate the work of the teacher and the success of the learner in a responsive classroom. Among the fundamental principles that support differentiation (not all of them shown on the concept map) are the following:

- A differentiated classroom is flexible. Demonstrating clarity about learning goals, both teachers and students understand that time, materials, modes of teaching, ways of grouping students, ways of expressing learning, ways of assessing learning, and other classroom elements are tools that can be used in a variety of ways to promote individual and whole-class success.

- Differentiation of instruction stems from effective and ongoing assessment of learner needs. In a differentiated classroom, student differences are expected, appreciated, and studied as a basis for instructional planning. This principle also reminds us of the tight bond that should exist between assessment and instruction. As teachers, we know what to do next when we recognize where students are in relation to our teaching and learning goals. We are also primed to teach most effectively if we are aware of our students' learning needs and interests. In a differentiated classroom, a teacher sees everything a student says or creates as useful information both in understanding that particular learner and in crafting instruction to be effective for that learner.

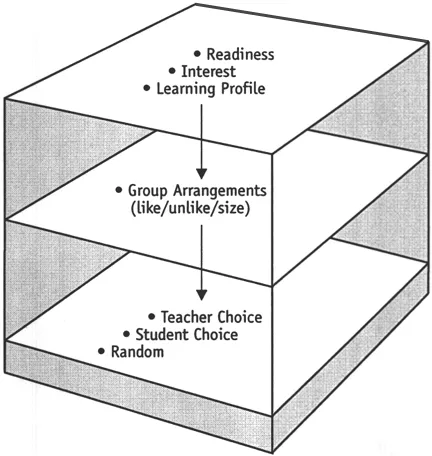

- Flexible grouping helps ensure student access to a wide variety of learning opportunities and working arrangements. In a flexibly grouped classroom, a teacher plans student working arrangements that vary widely and purposefully over a relatively short period of time. Such classrooms utilize whole-class, small-group, and individual explorations.

Sometimes students work in similar readiness groups with peers who manifest similar academic needs at a given time. At other points, the teacher ensures that students of mixed readiness work together in settings that draw upon the strengths of each student. Sometimes students work with classmates who have like interests. In other situations, students of varied interests cooperate toward completing a task that calls on all the interests. Students might work with those who have similar learning patterns (for example, a group of auditory learners listening to a taped explanation), and some tasks call for a grouping of students with varied learning patterns (for example, a student who learns best analytically with one who learns best through practical application). Sometimes working arrangements are simply random; students work with whoever is sitting beside them, or they count off into groups, or they draw a partner's name. Finally, in a flexibly grouped classroom, students themselves sometimes decide on their work groups and arrangements, and sometimes teachers make the call. Figure 1.2 shows the possible grouping combinations that can be achieved by mixing all the options between “levels” of the three-tiered diagram. Flexible grouping used consistently and purposefully has a variety of benefits: opportunity for carefully targeted teaching and learning, access to all materials and individuals in the classroom, a chance for students to see themselves in a variety of contexts, and rich assessment data for the teacher who “auditions” each learner in a wide range of contexts.

Figure 1.2. Flexible Grouping Options

- All students consistently work with “respectful” activities and learning arrangements. This important principle provides that every learner must have tasks that are equally interesting and equally engaging, and which provide equal access to essential understanding and skills. In differentiated classrooms, a teacher's goal is that each child feels challenged most of the time; each child finds his or her work appealing most of the time; and each child grapples squarely with the information, principles, and skills which give that learner power to understand, apply, and move on to the next learning stage, most of the time, in the discipline being studied. Differentiation does not presume different tasks for each learner, but rather just enough flexibility in task complexity, working arrangements, and modes of learning expression that varied students find learning a good fit much of the time.

- Students and teachers are collaborators in learning. While the teacher is clearly a professional who diagnoses and prescribes for learning needs, facilitates learning, and crafts effective curriculum, students in differentiated classrooms are critical partners in classroom success. Students hold pivotal information about what works and does not work for them at any given moment of the teaching-learning cycle, they know their likes and preferred ways of learning, they can contribute greatly to plans for a smoothly functioning classroom, and they can learn to make choices that enhance both their learning and their status as a learner. In differentiated classrooms, teachers study their students and continually involve them in decision-making about the classroom. As a result, students become more independent as learners.

Elements of Curriculum That Can Be Differentiated

Content. A teacher can differentiate content. Content consists of facts, concepts, generalizations or principles, attitudes, and skills related to the subject, as well as materials that represent those elements. Content includes both what the teacher plans for students to learn and how the student gains access to the desired knowledge, understanding, and skills. In many instances in a differentiated classroom, essential facts, material to be understood, and skills remain constant for all learners. (Exceptions might be, for example, varying spelling lists when some students in a class spell at a 2nd grade level while others test out at an 8th grade level, or having some students practice multiplying by two a little longer, while some others are ready to multiply by seven.) What is most likely to change in a differentiated classroom is how students gain access to core learning. Some of the ways a teacher might differentiate access to content include

- Using math manipulatives with some, but not all, learners to help students understand a new idea.

- Using texts or novels at more than one reading level.

- Presenting information through both whole-to-part and part-to-whole approaches.

- Using a variety of reading-buddy arrangements to support and challenge students working with text materials.

- Reteaching students who need another demonstration, or exempting students who already demonstrate mastery from reading a chapter or from sitting through a reteaching session.

- Using texts, computer programs, tape recorders, and videos as a way of conveying key concepts to varied learners.

Process. A teacher can differentiate process. Process is how the learner comes to make sense of, understand, and “own” the key facts, concepts, generalizations, and skills of the subject. A familiar synonym for process is activity. An effective activity or task generally involves students in using an es- sential skill to come to understand an essential idea, and is clearly focused on a learning goal. A teacher can differentiate an activity or process by, for example, providing varied options at differing levels of difficulty or based on differing student interests. He can offer different amounts of teacher and student support for a task. A teacher can give students choices about how they express what they learn during a research exercise—providing options, for example, of creating a political cartoon, writing a letter to the editor, or making a diagram as a way of expressing what they understand about relations between the British and colonists at the onset of the American Revolution.

Products. A teacher can also differentiate products. We use the term products to refer to the items a student can use to demonstrate what he or she has come to know, understand, and be able to do as the result of an extended period of study. A product can be, for example, a portfolio of student work; an exhibition of solutions to real-world problems that draw on knowledge, understanding, and skill achieved over the course of a semester; an end-of-unit project; or a complex and challenging paper-and-pencil test. A good product causes students to rethink what they have learned, apply what they can do, extend their understanding and skill, and become involved in both critical and creative thinking. Among the ways to differentiate products are to:

- Allow students to help design products around essential learning goals.

- Encourage students to express what they have learned in varied ways.

- Allow for varied working arrangements (for example, working alone or as part of a team to complete the product).

- Provide or encourage use of varied types of resources in preparing products.

- Provide product assignments at varying degrees of difficulty to match student readiness.

- Use a wide variety of kinds of assessments.

- Work with students to develop rubrics of quality that allow for demonstration of both whole-class and individual goals.

Student Characteristics for Which Teachers Can Differentiate

Students vary in at least three ways that make modifying instruction a wise strategy for teachers: Students differ (1) in their readiness to work with a particular idea or skill at a given time, (2) in pursuits or topics that they find interesting, and (3) in learning profiles that may be shaped by gender, culture, learning style, or intelligence preference.

Readiness. To differentiate in response to student readiness, a teacher constructs tasks or provides learning choices at different levels of difficulty. Some ways in which teachers can adjust for readiness include

- Adjusting the degree of difficulty of a task to provide an appropriate level of challenge.

- Adding or removing teacher or peer coaching, use of manipulatives, or presence or absence of models for a task. Teacher and peer coaching are known as scaffolding because they provide a framework or a structure that supports student thought and work.

- Making the task more or less familiar based on the proficiency of the learner's experiences or skills for the task.

- Varying direct instruction by small-group need.

Interest. To differentiate in response to student interest, a teacher aligns key skills and material for understanding from a curriculum segment with topics or pursuits that intrigue students. For example, a student can learn much about a culture or time period by carefully analyzing its music. A social studies teacher may encourage one student to begin exploring the history, beliefs, and customs of medieval Europe by examining the music of the time. A study of science in the Middle Ages might engage another student more.

Some ways in which teachers can differentiate in response to student interest include

- Using adults or peers with prior knowledge to serve as mentors in an area of shared interest.

- Providing a variety of avenues for student exploration of a topic or expression of learning.

- Providing broad access to a wide range of materials and technologies.

- Giving students a choice of tasks and products, including student-designed options.

- Encouraging investigation or application of key concepts and principles in student interest areas.

Learning Profile. To differentiate in response to student learning profile, a teacher addresses learning styles, student talent, or intelligence profiles. Some ways in which teachers can differentiate in response to student learning profile include

- Creating a learning environment with flexible spaces and learning options.

- Presenting information through auditory, visual, and kinesthetic modes....