![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction and Overview

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The impact of globalization is rapidly posing new and demanding challenges to individuals and societies. In this globalized world, people compete for jobs—not just locally but also internationally. At the Microsoft Partners in Learning Global Forum on November 8, 2011, U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan acknowledged that "education and global job markets are much more competitive today than even a generation ago," but he also noted that educators and nations need to work together to advance "achievement and attainment everywhere" (U.S. Department of Education, 2012, p. 1). Inherent in this statement is the notion that schools and students in the United States must remain competitive in order to support tomorrow's economy and American prosperity. Developing new cohorts of highly qualified and competitive workers requires a high-quality education system in every local community.

The United States must remain competitive globally, but it also needs to ensure that graduates have the skills necessary to enter a workforce that didn't even exist when they started school. Employment in the professional, scientific, technical, and computer systems fields—all fields that rely heavily on logic, reasoning, and critical thinking—is expected to increase by 45 percent by 2018 (U.S. Department of Labor, 2010).

Education expert Tony Wagner has conducted scores of interviews with business leaders and observed hundreds of classes in some of the nation's most highly regarded public schools (Wagner, 2008). As a result, he discovered a profound disconnect between what employers look for in potential employees (critical thinking skills, problem-solving skills, collaboration, creativity, and effective communication) and what our schools provide (passive learning environments and uninspired lesson plans that focus on test preparation and reward memorization). He notes that this problem exists not only in low-performing schools but also in top schools where skills that matter most in the global knowledge economy are not being taught or tested. (By global knowledge economy, we refer to the keen and growing competition across the world for high-end jobs—especially in the service sector—that are dependent on highly educated, creative individuals who can fulfill the requirements of the work and, more important, create new job opportunities.) Young people in the United States are effectively being equipped to work in job fields that are quickly disappearing from the economy, whereas young adults in countries such as India and China are competing for the world's most sought-after careers. We simply cannot afford this disconnect between what is taught in U.S. schools and what is required in the globally connected workplace.

Over the last two to three decades, while other countries have made significant improvements to their education systems, the United States has made only incremental changes. As a consequence, students in the United States lag in academic performance when compared with their peers in other industrialized nations, particularly in science and mathematics. The United States ranks well below places such as South Korea, Finland, Singapore, Hong Kong (a special administrative region of China), Shanghai (a province-level city under direct control of the Chinese central government), Japan, New Zealand, Australia, and Canada. The 2012 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Programme for International Student Assessment indicated that, of the 34 countries evaluated, the United States ranked 17th in reading, 21st in science, and 26th in mathematics (OECD, 2013). Twenty-sixth in math!

In this the-world-is-flat era, the United States and China demand more competitive human capital and, therefore, sustained investment in and development of human capacity. For the last few decades, such investment has been emphasized as an important factor contributing to economic growth. Continuous improvement of educational opportunities for young people is one of the best means of human capital investment, and it carries an enormous potential for payback. This is seen in improved student development and performance in order to master the skills that are necessary to compete globally (Baker, Goesling, & LeTendre, 2002; Chudgar & Luschei, 2009). For many years, researchers, policymakers, and educational practitioners in both the United States and China have explored the variables that impact student achievement. The issue of teacher quality has been the focus of discussion and debate time after time, since the classroom teacher is widely regarded as the most influential school-related factor that affects student achievement (Mendro, Jordan, Gomez, Anderson, & Bembry, 1998; Muijs & Reynolds, 2003; Stronge, Ward, & Grant, 2011). Teacher effectiveness is the pillar of educational policy agendas, and it mediates the impact that any instruction-related reform or intervention has on student learning (Stronge, 2010).

What is important for U.S. educators (indeed, for educators in any nation) to understand is that, even though we may be making incremental reforms and improvements, we aren't competing against a stationary goal. Rather, as educators in one country seek to improve, so do educators around the world. Thus, we're always aiming at a moving target. We must get better—substantially better—if we want to remain competitive and successful moving forward. Make no mistake—this is a highly competitive world in which we live and work.

Educational Reform

China

On the other side of the globe, China has undertaken a nationwide program of curriculum reform since 2001. This reform is considered to be one of the most ambitious and far-reaching changes to schooling in recent Chinese history (Sargent, 2006). In addition to an overhaul of the objectives and content of curriculum materials, it calls for a paradigm shift in educational philosophy and a corresponding transformation in teaching practices at the classroom level. This represents a significant shift away from the traditional Chinese model—which focused primarily upon memorization, drilling, and prescribed textbooks—to practices that foster individuality, self-expression, inquiry, and creative thinking skills. The traditional education system in China is often criticized for encouraging conformity, being highly examination-oriented, discouraging the development of students' creativity, and bolstering authoritarian teachers for whom the rigid and centralized curriculum is a more important agenda than catering to individual differences among students (Cheng, 2004).

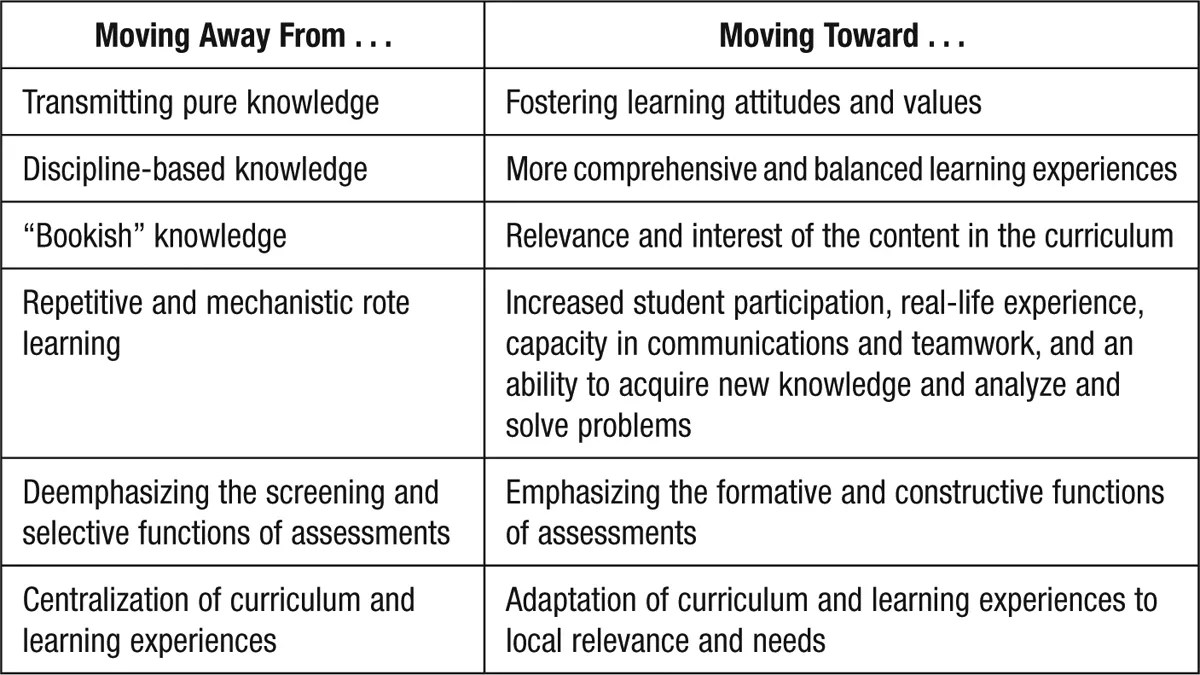

Preus (2007) observed that the national education reform movement in China has moved its educational system toward a decentralization of elementary and secondary education. The central government has taken steps toward loosening its control over curriculum and assessment. For instance, the government used to have complete control over the development and selection of textbooks. Under new guidelines intended to stimulate innovation and creativity, teachers at the provincial, local, and school levels are beginning to enjoy the autonomy to develop and select textbooks. Overall, China is striving to establish a "quality-oriented" rather than a "test-oriented" system. Guidelines for this nationwide reform (drafted by the Ministry of Education) call for changes that are represented in Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1. Nationwide Reform Changes in China

Already, these reforms are paying off. Shanghai is new to international assessment, but the city significantly outperformed even top-performing nations in all three subjects (OECD, 2010). As one of the most internationalized cities in China, Shanghai has been at the forefront of the country's educational reform. Although Shanghai cannot represent the whole country, its success indicates that China's move away from its traditional examination-driven system and to a system that aims to equip students with 21st-century skills is on track.

The educational system in Shanghai—and in China at large—has undergone several stages of development: the rigid Russian model during the 1950s, a period of "renaissance" in the early 1960s, disastrous damage during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), rapid expansion of basic education during the 1980s and 1990s, and in the 21st century a move toward higher education that is widely accessible to students across the entire country (OECD, 2010).

For readers who are not familiar with traditional Chinese culture or its customs, we would like to digress here to describe briefly what conventional Chinese classroom teaching looks like. Observers of Chinese classrooms share a common impression—namely, large class sizes with students sitting in rows of desks facing the teacher and the teacher leading nearly all of the classroom activities and doing most of the talking to reticent students (Fang & Gopinathan, 2009; Huang & Leung, 2004; Paine, 1990). It has been well documented that teaching in Chinese culture is defined by demonstration, modeling, repeated drilling, and memorization (Jin & Cortazzi, 2008).

Western observers of classroom instruction in China are also usually impressed by the discipline and concentrated attention of Chinese students, along with the rapid pace and intensity of teacher-centered interaction (Jin & Cortazzi, 2008; Marton, Dall'Alba, & Kun, 1996). Typically, classes in China are large—in excess of 50 students—and classroom interaction is teacher-centered and text-based. Instructional methods are largely expository, and they are overtly driven by external high-stakes examinations (Biggs, 1996; Cortazzi & Jin, 1996). The teacher is often deemed to be an authoritative model—someone who has expert knowledge and skills, upstanding moral behavior, and an answer for every question. With respect to students, they are quiet and careful listeners (Jin & Cortazzi, 2008). Paine (1990) described Chinese lessons as dominated by teacher talk. Teachers act as artistic performers, and students are the audience.

Such a learning environment is opposite to the ideal learning environment defined in Western literature. Western intuitive thinking would perceive that Confucian-heritage culture results in rote learning and low student achievement (Biggs, 1996). However, students of Asian origin have been able to excel on international examinations. This phenomenon has attracted much attention since the 1980s (e.g., Stevenson, Lee, & Stigler, 1986; Stevenson & Stigler, 1992; Stigler, Lee, Lucker, & Stevenson, 1982; Sue & Okazaki, 1990). It seems that the strategy of memorization used by Chinese students is not simply for rote learning but an important method to achieve a deep understanding in which subject content is internalized and actively reflected upon (Watkins & Biggs, 1996, 2001).

Teacher authority and suppression of individual expression are deeply rooted in Confucian and collectivistic cultures (Ho, 2001). In Chinese classrooms, there is a high expectation for members to conform to a uniform standard of behavior. Unlike Western cultures, where harmonious social relations rest upon the satisfaction of individual needs or rights and fairness to all, "proper behavior in the Confucian collectivistic culture is defined by social roles, with mutual obligation among members of society and the fulfillment of their duties for each other being emphasized" (Ho, 2001, p. 100). Another characteristic of Chinese education is its emphasis on basic knowledge and skills. Chinese teachers and learners tend to believe that basic skills are fundamental and must precede any effort to encourage higher-level learning (Cheng, 2004; Soh, 1999).

In Chinese culture, learning is believed to occur through continual, careful shaping and modeling, and higher-order learning—such as analysis, evaluation, and creativity—is demonstrated only after the child has perfected prescribed and approved performances (Cheng, 2004). Whole-class instruction is the prevailing strategy, and the teacher is perceived to be the "purveyor of authoritarian information" (Stevenson & Stigler, 1992, p. 18), transmitting knowledge through repetition and rote memorization to students who act as passive recipients. These characteristics of Chinese classrooms are in sharp contrast to what is found to be conducive to student learning in Western academics.

In U.S. classrooms, learning activities are much more student-centered, with teachers acting as facilitators and students actively participating in individual or group work. The focus on individualism found in Western culture suggests that learning is optimal when student self-expression is exploited and when students are engaged in exploration. In the West, educators believe that students learn best when they begin by exploring and then move to an understanding of concepts and development of skills. However, educators in China believe that understanding content must occur before creative exploration of the learned concepts (Biggs, 1996).

It is also worth mentioning that Western and Chinese theories about the dichotomy of nature versus nurture are also different. Generally, Chinese culture credits nurture over nature in human learning and achievement. The Confucian philosophy of learning and achievement places primary emphasis on nonintelligence factors—such as personality traits (e.g., motivation, perseverance, effort) and environmental factors (e.g., parental and familial support, teacher and school instruction)—rather than natural ability as the most important prerequisites for desired performance (Chen & Stevenson, 1995; Rosenthal & Feldman, 1991; Shi & Zha, 2000).

Confucius's lasting influence in history resides in his concept of ren which is "a lifelong striving for any human being to become the most genuine, sincere, and humane person he or she can become" (Li, 2003, p. 146). According to Confucius, the process of actualizing ren is a process of self-cultivation and self-perfection. He taught that the goal for an individual is the development of personality until the ideal of a perfect man, a true gentleman or sage, has been reached. Confucius believed that, within this developmental process, one's single-minded effort and consistent practice are more important than one's innate ability to achieve success (Tweed & Lehman, 2002). Ultimately, ideal status of ren is achievable by anyone striving for it.

Chinese teachers influenced by Confucian thinking tend to regard the possibility of overachieving or underachieving as under one's individual control rather than being predestined by natural ability. Research also reveals that Chinese and Western cultures have different attribution patterns and loci of control (Hau & Salili, 1991; Salili & Hau, 1994; Walberg, 1992). People from Chinese cultures tend to attribute success to effort and failure to lack of effort, whereas people from Western cultures tend to attribute success and failure to ability (or lack thereof). Gardner (1995) made the following comment regarding the phenomenon that East Asian students outscored their U.S. counterparts on IQ tests:

Genetics, heredity, and measured intelligence play no role here. East Asian students learn more and score better on just about every kind of measure because they attend school for more days, work harder in school and at home after school, and have better-prepared teachers and more deeply engaged parents who encourage and coach them each day and night. Put succinctly, Americans believe (like Herrnstein and Murray) that if you do not do well, it is because they lack talent or ability; Asians believe it is because they do not work hard enough. (p. 31)

United States

With the passing and implementation of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) in 2001, the U.S. federal government emphasized the need for states and school districts to ensure that all students—particularly at-risk students, students who are ethnically and linguistically marginalized, or students who are otherwise disadvantaged—have access to "highly qualified teachers." The NCLB law used three key guidelines to determine whether a teacher is highly qualified: (1) at least a bachelor's degree in the subject taught, (2) full state teacher certification, and (3) demonstrated knowledge in the subject taught (U.S. Department of Education, 2001).

The notion of effective teachers, as reflected in U.S. educational policies, has evolved considerably. For most of the 20th century, when candidates completed a state-approved teacher preparation program, they were eligible for teacher certification. In the 1980s, several states implemented performance assessments to ensure that teachers were equipped with a uniform set of competencies regardless of the content areas or grade levels they taught. Those competencies were largely drawn from process-product research on teaching and were perceived to be evidence-based. During the past 10 years, the standards used to assess teacher effectiveness have increasingly reflected the real complexities of classroom teaching. In particular, they emphasize the context-specific nature of teaching and the need for teachers to integrate knowledge of subject matter, students, and contextual conditions as they make instructional decisions, engage students in learning, and reflect on practice (Wayne & Youngs, 2003).

In order to improve the quality of schools and positively affect students' lives, teaching quality must be addressed. This is our best hope to improve education as a whole both systematically and dramatically. Curriculum can be reformed, but, ultimately, teachers must implement it. Professional development on new instructional strategies can be provided, but, ultimately, teachers must incorporate them into their instruction. There can be an increased focus on data analysis of student performance, but, ultimately, teachers must produce the results (Stronge, 2011). The highest-achieving countries around the world have committed significant resources to teacher training and support over the last decade. They raised standards and created stronger pathways for teacher education, providing teachers with more content and pedagogical knowledge. They paid their teachers well in relation to competing occupations, and they provided teachers with meaningful time for professional learning (Darling-Hammond, 2010).

In the early 1970s, less than half of...