![]()

Chapter 1

Globalization and Education

If Americans are to continue to prosper and to exercise leadership in this new global context, it is imperative that we understand the new global forces that we have both shaped and had thrust upon us. The alternative is to be at their mercy.

—Edward Fiske

***

The World Transformed

We used to think that people who thought the Earth was flat were uneducated. But Thomas Friedman's best-selling book, The World Is Flat (2005), helped us to understand that if the world is not exactly flat, then it is deeply interconnected as never before. Friedman's book described how technology and the fall of trade barriers have led to the integration of markets and nations, and enabled individuals, companies, and nation-states to reach around the world faster and cheaper than ever before. We see evidence of this interconnectedness in our lives every day—from the food we eat to the coffee we drink to the clothes we wear. Sports teams recruit talent from around the globe, and the iPhones we use to communicate are manufactured in more than 19 different countries.

This transformation of the world has happened relatively recently and in a short period of time. The economic liberalization of China beginning in the 1980s, the development of democracy in South Korea in 1987, and the fall of the Soviet Union and the development of free trade treaties in the early 1990s introduced 3 billion people, previously locked into their own national economies, into the global economy. Harvard economist Richard Freeman calls this the "great doubling" of the global labor force (National Governors Association, Council of Chief State School Officers, and Achieve, Inc., 2008, p. 9). In the late 1990s, the wiring of the world in preparation for the "millennium bug" unleashed another set of sweeping changes, as did the 2001 accession of China to the World Trade Organization and the 2003 economic liberalization of India, which jump-started that country's tremendous growth. The results have been staggering. Twenty years ago, bicycles were China's primary method of transportation, the G7 group represented the most powerful nations on earth, and the World Wide Web was just a proposal (McKinsey, 2011). Who at that time would have imagined the dramatic skyline of Shanghai today, that the G7 would become the G20, and that mobile web use would be growing exponentially around the world?

The effects of globalization have been far-reaching. While the living standards of the world are still highly uneven, 400 million people have moved out of extreme poverty since 1980—more than at any other time in human history. The growth and urbanization of a global middle class is creating huge new markets for goods and services of all kinds. Since 2000, despite frequent political and economic crises that cause it to dip temporarily, the global economy has been expanding (Zakaria, 2008). The world's economic center of gravity is also shifting: 50 percent of growth in gross domestic product (GDP) occurs outside the developed world, a fact that is fundamentally changing business models. Already, one in five U.S. jobs is tied to exports, and that proportion will increase (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004).

Globalization is often viewed as a zero-sum game in which one nation's economic growth comes at the expense of another. But the reality is more complicated than that. While manufacturing has largely moved out of the developed world into countries with lower labor costs, the exponential growth of the economies of India and China and the smaller-scale growth of other economies such as Russia and Brazil, have also created enormous demand for U.S. products—high-end industrial goods, cars, luxury items, agricultural products, and so on—and have increased the numbers of tourists coming to the United States and the numbers of undergraduate and graduate students flocking to American universities. Large multinational companies from other countries are building plants and providing jobs in the United States, and the lower prices of consumer goods from abroad benefit the American consumer. Still, while the global integration of economies has created complex webs of capital, trade, information, currencies, services, supply chains, capital markets, information technology grids, and technology platforms that form a more intricate, multifaceted system than a model of simple economic competition among nations, the competition for industries and for high-skill, high-wage jobs has undoubtedly become more intense.

This intensified competition stems from several sources. First, automation has eliminated large numbers of lower-skill jobs—far more than outsourcing has, in fact. Second, the "death of distance" caused by the global spread of technology, which makes it just as easy to create a work team around the world as it is to create one across a company, has put American workers in direct competition with workers elsewhere. Work that can be digitized can now be done with the click of a mouse by anyone from virtually anywhere in the world. Jobs in medical diagnostics, architectural drawing, filmmaking, tax preparation, and call centers are some of the types of occupations that have been outsourced. American students today are therefore competing not just with students in the city or state next door but with students in Singapore and Shanghai, Bangalore and Helsinki.

As the economy has become not just more global but also more knowledge based, the skill mix in the economy has changed dramatically. The proportion of workers in blue-collar and administrative support positions in the United States dropped from 56 percent to 39 percent between 1969 and 1999, leaving a trail of rust-belt neighborhoods and cities. Meanwhile, the proportion of jobs that are managerial, professional, and technical increased from 23 percent to 33 percent during the same period (Levy & Murnane, 2004). Skill demands within jobs are increasing too. Jobs that require routine manual or cognitive tasks are rapidly being taken over by computers or lower-paid workers in other countries, while jobs that require higher levels of education and more sophisticated problem-solving and communication skills are in increasingly high demand. The jobs that once supported a middle-class standard of living for workers with a high school diploma or less have substantially disappeared. These new economic realities and rapid shifts in the job market are fundamentally changing what we need from our education system.

The rapid increase in emerging markets also means economic growth and the need to prepare students for jobs that require new skill sets. According to the Committee for Economic Development (2006) "to compete successfully in a global marketplace, both U.S.-based multinationals as well as small businesses, increasingly need employees with knowledge of foreign languages and cultures to market products to customers around the globe and to work effectively with foreign employees and partners in other countries" (pp. 1–2).

And it is not just the economy that has become more global. The most pressing issues of our time know no boundaries. Challenges facing the United States—from environmental degradation and global warming, to terrorism and weapons proliferation, to energy and water shortages, to pandemic diseases—spill across borders. The only way to address these challenges successfully will be through international cooperation among governments and organizations of all kinds. As the line between domestic and international continues to blur, American citizens will increasingly be called upon to vote and act on issues that require greater understanding of other cultures and greater knowledge of the 95 percent of the world outside our borders.

In the 20th century the United States was "the most powerful nation since Imperial Rome" (Zakaria, 2008, p. 217), dominating the world economically, culturally, politically, and militarily. While the United States still remains a military superpower and supports the world's largest economy, the rapid economic growth and expansion happening in other countries show that a country's global position cannot be taken for granted. A great transformation is taking place around the world—and it is taking place in education, as well.

The Growing Global Talent Pool

In the second half of the 20th century, the United States was indeed the global leader in education. It was the first country to achieve mass secondary education. And while European countries stuck to their elite higher education systems, the United States dramatically expanded higher education opportunities through measures like the G.I. Bill after World War II. As a result, the United States has had the largest supply of highly qualified people in its adult labor force of any country in the world. This tremendous stock of highly educated human capital helped the United States to become the dominant economy in the world and to take advantage of the globalization and expansion of markets.

However, over the last two decades, countries around the globe have been focused on expanding education as the key to maximizing individual well-being, reducing poverty, and increasing economic growth. Under the Education for All initiative, one of the United Nations' Millennium Development Goals, nations have joined together with the goal of providing universal primary education in every country, especially the poorest countries, by 2015. Although there is still a long way to go to meet this goal, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, among girls, and in war-torn areas, more than 33 million children were added to school rolls between 2000 and 2008 (UNESCO, 2010). Countries in the middle tier of economic development aspire to universal secondary school graduation. And the most developed countries have set the goal of greatly increased levels of college attendance.

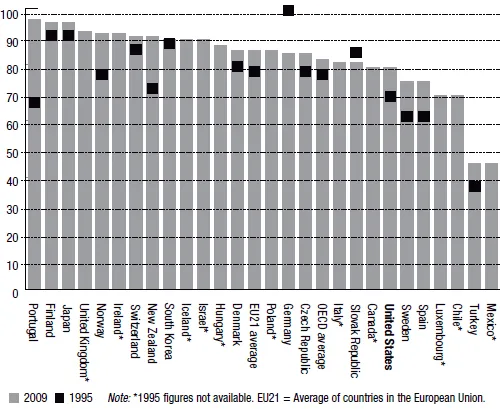

Because of dramatic global educational gains, high school graduation has now become the norm in most industrialized countries. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports that by 2009, the United States had fallen from 1st in the world to 8th in the proportion of young adults (ages 18 to 24) receiving a high school diploma within the calendar year. This lower position does not indicate a drop in U.S. graduation levels; rather, it testifies to the success other nations have had ambitiously expanding their secondary school systems and raising their graduation rates. Although the United States actually showed a modest increase in secondary school graduation from 1995 to 2009, this achievement is dwarfed by the striking gains of a number of countries (see Figure 1). Among the 28 OECD countries with comparable data for 2009, the United States ranked 12th in the percent of the overall population (including adults over the age of 24) achieving secondary school graduation, which is 15 or more percentage points behind countries such as Portugal, Slovenia, Finland, Japan, Ireland, and Norway (OECD, 2011).

Figure 1. Percentage of Population Achieving High School Graduation or Equivalent

Source: Data from Table A2.1 (Upper secondary graduation rates [2009] and Table A2.2 (Trends in graduate rates at upper secondary level [1995–2009]. OECD. (2011). Education at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

The pace of change in high school graduation in some countries has been astounding. For example, two generations ago, South Korea had a similar economic output to Mexico and ranked 24th in education among the current 30 OECD countries. Today, South Korea is in the top 10 countries in terms of high school graduation rates, significantly ahead of the United States (Uh, 2008).

At the higher education level, the United States has a strong system that is admired around the world and is a world leader in research. According to the 2010 Times Higher Education World University rankings, 18 of the top 20 universities in the world were in America. And the United States is among the world leaders in the proportion of 35- to 64-year-olds with college degrees, reflecting the enormous expansion resulting from the G.I. Bill and, subsequently, the large numbers of people in the baby boom generation who went to college. But the United States falls to 10th place in the rankings when it comes to the proportion of younger adults age 25 to 34 who have an associate's degree or higher (National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, 2008).

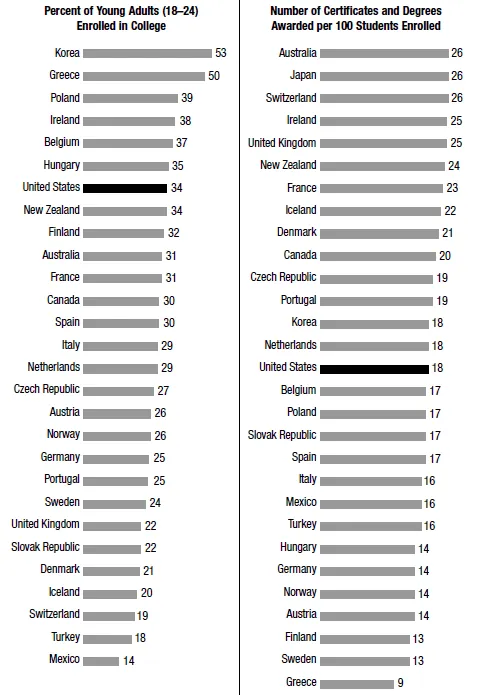

As recently as 1995, the United States tied for first in university and college graduation rates. But by 2008, it ranked 15th among 29 countries with comparable data, behind countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Japan, United Kingdom, Switzerland, and France. In the 1990s, when the importance of a highly educated workforce in the global economy was becoming ever clearer, other countries began to dramatically expand their higher education systems, as the United States had done in earlier decades. But during that period, there was almost no increase in the college-going rate in the United States. In addition, U.S. college dropout rates are high: only 54 percent of those who enter American colleges and universities complete a degree, compared with the OECD average of 71 percent. In Japan, the completion rate is 91 percent (National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, 2008). Overall, the United States has lost ground in such international comparisons as the pace of higher education expansion has accelerated around the globe. While older generations of Americans are better educated than their international peers, many other countries have a higher proportion of younger workers with completed college degrees (National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, 2008; see Figure 2).

Figure 2. College Attendance and Completion Statistics

The United States is a leader among OECD countries in the numbers of young adults enrolled in college, but ranks in the bottom half with regard to college completion.

Source: From Measuring Up 2008: The National Report Card on Higher Education (p. 8), by the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, 2008, San Jose, CA: Author. Available: http://measuringup2008.highereducation.org/print/NCPPHEMUNationalRpt.pdf

This development of educated talent around the globe means that, going forward, the United States will not have the most educated workforce in the world as it has had in the past. Nowhere is this expansion of education more dramatic than in Asia.

The Challenge from Asia

The rise of Asia is one of the most critical developments of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. From 1980 to 1990, Japan boomed, with world-class companies like Sony, Honda, Toyota, and Nissan achieving great success in industries where the United States had once been dominant. The so-called "Asian tigers"—South Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong—leapt forward and developed influential economies out of all proportion to their tiny size. China's GDP tripled between 1980 and 2003, increasing from USD$12 trillion to USD$36 trillion, making it the world's second-largest economy; it is expected to grow to USD$60 trillion by 2020 (Tierney, 2006). If current economic growth rates continue, it's only a matter of time before China overtakes the United States as the world's largest economy. Since India liberalized its economic policies in 2003, its economy, like China's, has been growing at a rate of 8 to 9 percent per year; by 2030, India is expected to overtake China as the nation with the largest population in the world, leading it to become a potentially even more significant player in the global market.

During this period, hundreds of millions of people have risen from poverty to form an enormous new middle class. But while Asia's extraordinary economic growth is the stuff of daily business headlines, less well-known is the region's equally remarkable educational trajectory. Of the 65 countries and provinces participating in OECD's 2009 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), the results of which were released in December 2010, most of the top performers were in Asia. Shanghai and Hong Kong led the way, followed by Singapore, South Korea, and Japan.

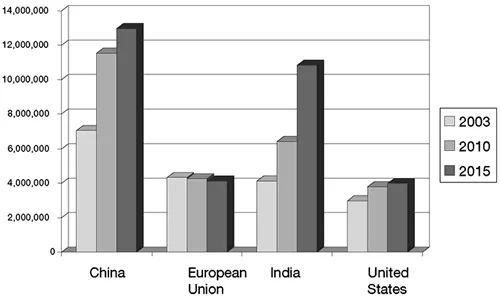

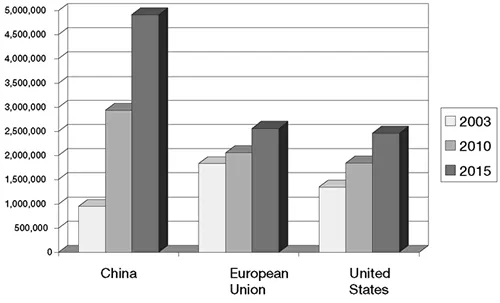

In terms of scale, the challenge to the United States has only just begun. A fundamental shift in the global talent pool is under way. Looking ahead to 2020, the U.S. proportion of that global talent pool will shrink even further as China and India, with their enormous populations, rapidly expand their secondary and higher education systems (see Figure 3). In the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s in China, there were almost no students in school. Today, nine years of basic education are universal in all but the most remote areas, and China's goal is to have 90 percent of students in upper secondary school by 2020. If the U.S. high school graduation rate remains flat and China continues on its current path, China will be graduating a higher proportion of students from high school within a decade. And China has 200 million students in elementary and secondary education, compared with our about 66 million.

Figure 3. Projected Future Supply of Secondary School Graduates

Source: From "Seeing U.S. Education Through the Prism of International Comparison" (slide 13). Presentation by A. Schleicher at a meeting of the Alliance for Excellence in Education, Washington, DC, October 4, 2007. Adapted with permission.

At the college level, according to the Chinese Ministry of Education, China has more than 82 million people who have received higher education, a small proportion of the population but still a number greater than America's 31 million college graduates. China expanded the number of students in higher education from 6 million in 1998 to 31 million in 2010, going from almost 10 percent to about 24 percent of the age cohort (Chinese Ministry of Education, 2010; see Figure 4). And many of these students are studying science and engineering. Harold Varmus, Nobel laureate, head of the National Cancer Institute, and cochair of the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, observed, "In the 20th century, U.K. observers saw U.S. education as overtaking the United Kingdom. In the 21st century, arguably, China may soon be exceeding the United States in education" (Varmus, 2009).

Figure 4. Projected Future Supply of College Graduates

Source: From "Seeing U.S. Education Through the Prism of International Comparison" (slide 14). Presentation by A. Schleicher at a meeting of the Alliance for Excellence in Education, Washington, DC, October 4, 2007. Adapted with permission.

India has been behind other countries in expanding secondary education; currently, only 40 percent of students of an age to be enrolled in secondary school actually are. But having succeeded in massively expanding primary education over the past two decades, India is now making major investments in secondary education, with the goal of universalizing lower secondary education by 2017 and sharply increasing enrollments in upper secondary school. The Indian government established a National Knowledge Commission (2006–2009) to make recommendations for policies that would help establish a "vibrant, knowledge-based society" based on research, technology transfer, and knowledge and skill development ...