![]()

Chapter 1

Where Did We Go Wrong?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

To start the conversation about school safety, we must first confront a rather thorny question: Why haven't we "solved" our school safety problem? Why, as a country and a profession, is our interest in and attention to school safety only ever short-lived, reactive, and episodically focused on the most recent school tragedy?

Our experience and research indicate two contributing factors that we will discuss in this chapter: the lack of consistent information and recommendations for safety practices, and the fragmentation of information and resources between the educational and emergency response communities. We also will discuss the harsh truth that as a society we do not seem concerned enough about school safety to make it a national priority. It is our greatest hope that the loss of 17 more lives in the February 2018 Parkland, Florida, shooting will be the catalyst needed for substantive change. In addition, we will address the competing priorities and dilemmas that schools face, including academic performance versus safety (both of which are enmeshed in the need to maintain accountability and its related assets of trust and reputation), buying "stuff" instead of training people, competing interests in resource allocation, and the highly centralized structures for safety decision making that exist in school settings. Finally, we'll take a moment to discuss two concepts that contribute to the current lack of school safety preparedness: the "incredulity response" and the "normalcy bias." Throughout the chapter, an underlying theme is the moral and ethical responsibility of educators to ensure the safety of the children in their care and to give priority to safety above academics, public relations, and finances.

How Much Do We Care About School Safety?

It seems at best out of touch and at worst deliberately provocative to say that, as a nation, we don't care about school safety. Since 1977, the Gallup Work and Education Poll has asked parents whether they fear for their child's physical safety while at school. The percentage of parents who have fears about the safety of their child's school started at 24 percent in 1977 and has subsequently ranged from a low of 15 percent in 2009 to a high of 55 percent after Columbine in 1999; as of late 2017, the number hovers at around 24 percent (Jones, 2017). School safety is, and has been, on the minds of parents.

Yet, unless an event has just recently occurred in a school, outside of the relatively small world of crusaders, consultants, and conferences, we as a society don't really care that much about school safety. Educators and administrators are overworked, underresourced, scrutinized to within an inch of their lives, and sometimes used as a political football. Should it even be a surprise that they don't have the ability to adequately prepare for events that seem unfathomable?

As a nation, we get hyperfocused on the injustices of bullying. Although bullying is definitely an important challenge for kids in schools today, a big business has grown up around it. It seems that everyone has an antibullying program that costs lots of time and money. Some parents and community members (and some educators) blame bullying for every issue a student encounters. School leaders are willing to create programs, invest funds, and allocate time, attention, and training to bullying, all in the name of convincing our students that schools are safe places to learn. Yet many of these same schools have no crisis plans or have plans that are outdated or not comprehensive (not covering all possible hazards); have not adequately trained their staff, students, or parents; and generally don't acknowledge the reality that a crisis event of some sort will occur. In short, despite our fears and well-intentioned efforts, schools are shockingly underprepared to face even the most common crises.

The good news is that most schools won't face a catastrophic event like the tornado that destroyed multiple schools in Joplin, Missouri, or the shooting in the library at Arapahoe High School in Centennial, Colorado. The sobering reality is that our students know when we are prepared to keep them safe and when we are not. Our youngest students regularly participate in fire drills; they learn how to exit the building to safety. But most important, they learn that we have a plan, we have the situation under control, and we are prepared to keep them safe. We often hear from parents who tell us that their children don't want to return to school after hearing about a school bomb threat or shooting. Because safety planning and crisis response have not been discussed, practiced, or demonstrated, these children do not believe that their school is safe or that their teacher has the capacity to keep them safe. How is this acceptable? Why are we as a society or as parents not more concerned about this?

What Is the State of School Safety Today?

The section heading is a bit of a loaded question because the rate of incidents, the number of fatalities, the perceptions of staff, students, and parents about safety, and a variety of other measures can change overnight if and when the "next" Columbine, Sandy Hook, or Parkland occurs. In addition, because there is no standardized national reporting system for safety issues in schools, it is difficult to capture an accurate picture of the state of school safety. As a result, we began our own longitudinal study to try to objectively quantify the frequency, scope, nature, and severity of threats and incidents of violence in schools. Thus, we can make some general statements about past rates of violent incidents and threats in schools. According to our own research, during the 2016–2017 school year, there were more than a dozen threats of violence made against schools in the United States every day. As of this writing, the first half of the 2017–2018 school year saw a dramatic increase in the number of violent incidents from the year before. (Check out the most recent school year's report as well as where your state ranks in the States of Concern report by accessing the Resources section at www.eschoolsafety.org/resources.) Even more alarming, an actual incident of violence occurred in a school on a daily basis (Klinger & Klinger, 2017).

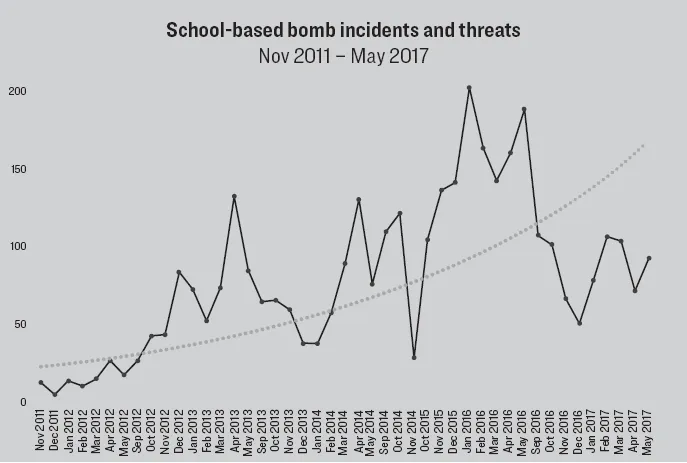

The 2015–2016 school year saw an unprecedented increase in school-related bomb threats both in the United States and throughout the world. As shown in Figure 1.1, the 1,267 bomb threats that occurred reflected a 106 percent increase from the same time period in the 2012–2013 school year (Klinger & Klinger, 2016).

Figure 1.1. School-Based Bomb Incidents and Threats

© 2011–2017 The Educator’s School Safety Network. www.eschoolsafety.org

Graphs and/or data may not be republished without this disclaimer and other proper attribution.

In addition to a dramatic increase in the number of bomb threats, other concerning trends emerged in the United States related to the scope and frequency of the events (more than 7,000 schools affected), the delivery methods of the threats (21 percent robocalls), the atypical locations of the incidents (44 percent at elementary schools), and the rate of actual detonations in schools (four in one year alone). For more specifics on our research into bomb threats and incidents in schools, consult the Bomb Incidents in Schools report listed in the Resources section of this book and available at www.eschoolsafety.org/resources.

Despite the number of threats and incidents, school administrators find themselves in the untenable position of having to make critical decisions about crisis response with few established best practices, outdated protocols, and a lack of education-based training that could help them understand the potentially catastrophic effects of a detonation and provide the requisite skills to respond appropriately and effectively to a bomb threat or incident. Based on our analysis of bomb-threat data and trends, the sobering reality is that at some point, an explosive device will be detonated in a U.S. school with significant consequences, and we must be ready. The question that must be considered is not if an explosive device will be detonated in a school, but when.

Although catastrophic school shootings and massacres are few and far between, the threat of such an event exists in all schools, every school day. The first critical step is to shift the thinking about school safety from an occasional concern to an everyday operation for educators that involves planning for, preventing, and responding to safety threats.

Academics Versus Safety: Why Must We Choose?

The focus of modern public education in the United States has always alternated between "academics" and the "whole child." There has always been this push-pull between those who want strong accountability systems with a rigorous "traditional" curriculum and those who see the critical need for a school program that speaks to all aspects of a child's development. Despite the seemingly dichotomous position of these two camps, they have in common the desire for all students to achieve their fullest potential. Our hope is that this book will fulfill the promise of educating the whole child, with safety as the bedrock.

Despite Maslow's identification of safety as the most basic need after food and water (Maslow, 1943), the safety of children in school settings has traditionally taken a backseat to the primary mission of schools—to educate children. Yet this priority of academics over safety is counterproductive. Meta-analyses of research on the effect of school violence and perceptions of school safety on achievement clearly establish two important truths. The first is that when violence occurs in a school, learning stops—not exactly a groundbreaking revelation. The second, more subtle indication of the research is that when students feel that violence might occur, learning is suppressed. The mere perception of potential danger is enough to decrease academic achievement (Prevention Institute, n.d.). As then–Secretary of Education Arne Duncan put it at the 2011 National Forum for Youth Violence Prevention, "No school can be a great school unless it is a safe school."

Too often, students' perceptions of their school as an unsafe place are disregarded or minimized, primarily because perception isn't as measurable or definable a metric as "X number of violent events took place in this school." Many possible factors, such as a school demonstrating a plan for safety (or not) or how empowered (or intimidated) students feel as a result of conversations and trainings on school safety, can affect students' perceptions and beliefs about how safe a school is. In our work with schools we often talk about "unowned" areas in schools—those places where students don't feel safe or where they know violence or other misbehavior occurs. Students don't necessarily categorize these areas as "unowned" or "unsafe," but when asked where a student would go to beat someone up, smoke weed, or make out, students invariably are able to identify specific places in their school (e.g., stairwells, remote hallways, unlocked vacant areas) where they know (or at least perceive) that unsafe activities occur. When we ask administrators where the unsafe or unowned areas in their school are and they say they don't know, we tell them to ask the kids. Your students are most likely well aware of areas in your school that are unsupervised and potentially unsafe.

Many people have the misguided idea that educators should not discuss violence in schools with students because it makes the students anxious. Teachers, administrators, and boards pretend that school safety and violence prevention do not need to be discussed because violence doesn't ever happen in "our" schools. Let us assure you that students are well aware that violence occurs in U.S. schools and that bad things could happen in any school. A school's collective unwillingness to discuss that possibility doesn't alleviate anxiety. In fact, our experiences with schools and students indicate that what really makes students anxious is not that a crisis might occur, but that the adults in the school don't seem to know what to do about it!

In Amy's career as a building principal, she was always very concerned about academics, so she understands the emphasis and concern about the instructional program as justifiable and important. We are not saying that schools shouldn't be concerned about student success and mandated accountability measures like test scores. In fact, if you really want to improve your students' academic performance, improve the way you plan for, prevent, and respond to crisis events (not just violence) in your school. Show your students that their school is a safe place. More learning will take place if your students know that, if something bad does happen, there is a plan and everyone knows what to do.

The Assets of Trust and Reputation

Current accountability and assessment systems are centered on the idea that a transparent review of a school's academic performance on standardized measures will result in improved outcomes derived from legislated incentives and sanctions as well as public pressure and competition. In other words, schools want to establish a reputation as high-performing institutions of excellence. Unfortunately, just as low test scores and high dropout rates can obscure the great improvements that are occurring in a given school, so can rumors of fights, drugs, and bullying or an ineffective response to a previous crisis event.

A few years ago, we attended a panel discussion of representatives from several Ohio institutions that had fallen victim to violence on their campuses. We were particularly moved by a marketing staff member from Kent State University. This man explained that his most important job at the university was to make sure that it was known for something other than the terrible events of May 4, 1970. In our work throughout the United States, the truth of this remark becomes so clear in our presentations. Almost everyone knows of Kent State University, but only for that single event, not for its myriad other valuable contributions to higher education. The people at Kent State get it; they understand the value of trust and reputation and continue trying to refocus the narrative.

It's frustrating to us to see the amount of time and energy that schools put into community relations—hosting innumerable breakfasts and family nights, pushing out feel-good stories on social media, holding informational meetings and parent forums—in an attempt to establish a relationship of trust and maintain a solid reputation. Yet so many overlook the most viable threat to their efforts: a lack of safety planning and preparation. Great test scores and beautiful facilities don't matter if the school is perceived as a place where harassment, drugs, and intruders run rampant. The bottom line is that while parents will forgive a dip in test scores or a lower grade, they will never forgive or forget if a traumatic event, an injury, or a death happens to their child in your school.

Demonstrating the Value of Safety

While we're talking priorities, we can also examine the allocation of resources in schools. It's well established that what we value and find important, we spend money on. That's why people want nice houses, lots of toys for their kids on birthdays and holidays, and ridiculous sweaters for their dogs. In most schools, although there isn't an abundance of money being spent, there are fairly nice athletic facilities, decently equipped and outfitted marching bands, and relatively extensive playgrounds. An examination (American Association of School Administrators, 2010) of the operating budgets of most schools shows that 80–85 percent of the expenditures go to salaries—as it should, because education is a people business. Yet if we look at what is spent on training and professional development, the amount is very little, and what little there is typically isn't being spent on safety training.

More frustrating is the fact that when money is spent on safety in schools, it is most often expended on "stuff," not people, in a knee-jerk reaction to a specific event, with the goal of being able to point to the shiny metal detector or the fancy software and say to parents, "Look! Your kids are safe now!" Unfortunately, this claim is simply not true.

If the desire is to make schools safer from the myriad of natural and human-caused threats they face (not just an active shooter), then it takes a comprehensive approach in which the resources of time, money, and personnel are allocated in a strategic, ongoing fashion. Simply buying stuff or holding a "one and done" training event will contribute little if anything to progress in planning for, preventing, and responding to the many potential crisis events schools face.

In response to high-profile active shooter events in schools, such as those at Columbine, Sandy Hook, and Parkland, there has been an overemphasis on introducing full-time law enforcement into schools, usually through a school resource officer (SRO) or community police officer. Although this expensive proposition seems to solve some superficial problems and is clearly a public relations win, there is a need to critically examine the role of law enforcement in schools. This is where it gets touchy. To question the validity and value of a law enforcement officer in a school is often seen as rooted in opposing law enforcement, but this isn't the case. Educators have a professional obligation to objectively assess and evaluate every program that is implemented in schools.

We can point to many instances where the presence of a law enforcement officer in a school quite literally saved lives. That fact is a given. The resource officer on site at the 2013 Arapahoe High School shooting was a factor in shortening that event to a mere 87 seconds, although lives were still lost. We can't, however, measure the number of times the presence of a police officer was a deterrent to a violent act that never occurred as a result. We also know that well-trained school resource officers can form positive, trusting relationships with students that can help improve strained relationships between law enforcement and the communities they serve.

Conversely, we can also examine numerous instances in which officers in schools have reacted with excessive force (remember some of the shocking videos that showed up on the nightly news from schools in San Antonio, Baltimore, and Columbia, South Carolina), made errors in judgment (such as the accidental discharge in a Michigan school as the officer "showed someone" his weapon), or did not adequately anticipate the unique attributes of the educational situation they were in (exemplified by the 3rd grader who took the gun from a guard's holster in a South Carolina school).

Schools require an officer who has a foot in both worlds: law enforcement and education. Like teachers, an officer needs to have adequate training that is specific to education. A crisis event in a school is not the same as a crisis event in a shopping mall and cannot be treated as such. Police officers are often placed in educational settings without the benefit of understanding the different culture in which they are working. They cannot automatically overlay the same law enforcement principles and procedures used elsewhere on the school setting.

In September 2016, the U.S. Department of...