![]()

Chapter One

The Report of My Death Was an Exaggeration

“I saw it dying. I saw it dead. And I saw it coming out of the grave, rising from the ashes…”

—Gerhard Blum, Sony Music Entertainment

[Vinyl emerges from oblivion, providing the most unlikely comeback story of the digital age.]

The Billboard headline on May 11, 1991, screamed somewhat ominously, “The LP’s Passage to Oblivion,” announcing that the distribution companies owned by the major labels Warner/Elektra/Atlantic and Sony Music were no longer accepting returns from retailers on vinyl albums. Universal’s distribution group wasn’t either. Twenty years ago, six major record conglomerates (EMI, BMG, and Polygram since folded into three—Universal, Sony, and Warner) rode the compact disc (CD) as the cash-cow music format of choice. The internet, as a means of electronic distribution, still was a decade away from being a commercial option, playing catch-up from Napster’s illicit wakeup call.

Looking back on the past three decades, two popular analog home entertainment formats (vinyl and cassette, which were actually the most popular formats in the late 1980s) were quickly replaced by supposed advanced digital technologies in fast succession (CD, digital downloads, and streaming). Then—no doubt thanks to Record Store Day’s emergence in 2008—vinyl reemerges as a deluxe product where consumers are willing today to pay twice as much for a newly pressed vinyl LP than they did for a CD!?!

Did RSD’s cofounders know for sure what they were doing? Of course not, and they were largely making it up as they went along. Record stores were selling mostly CDs in 2007 and some couldn’t fathom stocking new vinyl once again in any kind of meaningful numbers, even though regular customers would always buy the three-dollar records in the used bins. But Michael Kurtz, who’s become the face of the movement, and his band of RSD misfits persevered, mustering enough support to make a much bigger splash by 2009, only to continue to build year after year the monumental achievement that Record Store Day has become fifteen years later.

Record Store Day is a celebration of record stores—thus the “record store” in the name—but it is full of misconceptions, such as it was started as a ploy of the major labels, or the RSD cofounders and the record stores that sell the exclusive records all get rich off these limited editions, or RSD releases clog up the pressing plants so that other vinyl records can’t get manufactured. All completely untrue.

Vinyl’s rebirth in the digital age defies all economic, technological, and ecological logic. Firstly, it’s expensive to manufacture an LP that, secondly, relies on mostly antique pressing equipment and processes, which largely haven’t changed in a half century. And thirdly, records are made from polyvinyl (PVC), which is not the most green-friendly raw material, although today’s pressing plants are far more conscious about sustainability than their 1970s counterparts, using modern processes and new equipment that reduce carbon emissions.

Record Store Day deserves substantial praise for kickstarting the entire vinyl supply chain, creating new opportunities for distribution companies, mastering and cutting facilities, raw material suppliers, packaging firms and printers, designers who create album graphics, turntable manufacturers, and ancillary products such as record sleeves and disc cleaning kits. It’s no coincidence that vinyl’s exponential growth year-to-year over the past fifteen years syncs up exactly with RSD’s launch and the positive impact the 1,400 indie record stores feel in their communities.

Speaking at the Making Vinyl conference in Hollywood in October 2019, David Bakula, senior vice president of Analytics, Insights, and Research for Nielsen Music/MRC Data, credited Record Store Day with “incredible foresight” to kickstart the vinyl comeback in 2008 when Bakula worked for a large distribution company. “After the [first] Record Store Day numbers came out, I went to my [boss] and said, ‘I’m telling you, man, this vinyl thing, there’s something here. This isn’t just about Record Store Day. These numbers are overperforming every single week.’ And he said to me, ‘It’s a rounding error, come back to me when it matters.’ Well, it sure didn’t take very long for it to matter.”

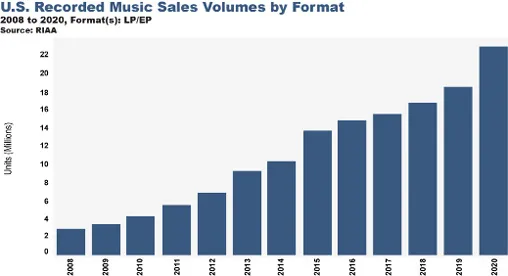

By 2012, Nielsen reported vinyl represented 2.4 percent of the physical music business with 3.3 million units (with CDs accounting for the balance). In 2013, it grew to 3.5 percent of the physical business and 4.3 million units. In 2014, the jump went to 6.2 percent and 6.4 million units. In 2015, the steady growth went to 8.8 percent and 8.4 million units, followed by 11.2 percent and 9.5 million units in 2016. In 2017, the vinyl jump rose to 14 million units, and again in 2018 to more than 16 million units. In 2019 Bakula forecasted that vinyl was trending at 24 percent of the physical business. And in 2020, the Record Industry Association of America’s (RIAA) reported that vinyl grew 28.7 percent to $626 million, which was more revenue that came in for CDs for the first time since 1986.

These numbers tell a positive story. But the problem is most record stores do not report their sales, so both Nielsen and RIAA estimate figures that unfortunately don’t jibe with the large volumes pressing plants crank out these days or pumped through the retail supply chain. Yet the media’s spread vinyl sales numbers that severely underestimate the market. In the US, record stores only buy titles that they are certain will be bought by music fans because they cannot be returned. Furthermore, only about 250 independent record stores in the United States report their sales to MRC Data, who clearly is estimating sales, since approximately 1,400 US stores participate in Record Store Day.

Sitting in the audience in the October 2018 Making Vinyl conference were representatives of the industry’s leading pressing plants and distribution companies. When my PowerPoint presentation flashed an RIAA slide from two weeks earlier that reported 8.1 million vinyl units were sold in the first six months of that year, yells echoed throughout the ballroom that it was “way low.” Afterward, Steve Sheldon, owner of the Rainbo, one of the world’s largest vinyl pressing plants, said his California pressing plant at that point was cranking out 7 million units a year alone. United Record Pressing in Nashville, the nation’s largest manufacturer, produced more LPs than Rainbo (which closed in January 2020 due to the high cost of doing business in California). Then there’s additional output from twenty-seven other smaller US facilities, not to mention the sixty-three other plants around the world also making records, a good portion no doubt being imported for American consumers. Globally, 160 million records were pressed in 2021, estimated Making Vinyl.

Now put those numbers into perspective: Back in 2008 when Record Store Day launched, there were only fourteen pressing plants in the United States and eight more elsewhere in the world for a total of twenty-two operated with a last-man standing attitude. New operations sprung up during the past decade to meet the demand. But current pressing capacities globally add up to 160 million LPs a year, but demand by June 2021 required twice that amount, creating a backlog as much as ten months, Billboard reported.

Market research firm Deloitte nearly broke the internet in 2017 by estimating vinyl that year would be a $1 billion industry for the first time in decades. The firm took into account not only newly pressed vinyl, but also the sale of used records, turntables, and accessories. Since then, vinyl and ancillary revenue demonstrated, as of this writing, more than three years’ worth of substantial growth. But Deloitte’s Duncan Stewart, one of the 2017 report’s two authors, won’t quantify the market’s current worth. “I can’t just ‘update’ the number. Deloitte has rules and processes around this kind of thing,” he says.

At Making Vinyl Virtual in December 2020, though, Stewart stated, “We think that the US number for [new vinyl sales] will be well over $500 million this year,” partly based on flawed RIAA numbers, which “understate actual vinyl sales. They don’t capture a lot of the small record shops; they don’t capture sales of used vinyl. So the actual number, of course, would be even higher still.”

However questionable RIAA’s methodology might be, the organization’s report for the first half of 2020 found vinyl album revenues of $232 million to comprise nearly two-thirds (62 percent) of total physical music revenues. That was quite a milestone, marking the first-time vinyl’s dollar amounts exceeded that for CDs since the 1980s. (Interestingly, the report stated the volume of CD units still exceeded that of vinyl.)

Meanwhile, Deloitte’s Stewart estimated in December 2020 that the US is 40 percent of the global vinyl market, which the firm in 2017 reported “came very close to a billion dollars [in 2017]… Our prediction came true.” The researcher cited vinyl’s “decent growth” in 2018 and 2019, and “a big jump even in the middle of a pandemic for 2020…Even post-pandemic, we’ll be spending considerably more time at home. People are setting up their home offices, they are putting in sound systems, they are buying vinyl, and pulling vinyl out of storage.”

Vinyl 2.0 is not your father’s record business. New machinery suppliers have perfected nearly century-old processes with higher yields, sustainability, better-sounding, heavier, and creatively packaged records. “This is craftsman-level stuff,” Jeff Truhn, operations manager of Cascade Record Pressing in Milwaukie, Oregon, told the Making Vinyl audience in 2018.

LPs produced for Record Store Day are pressed in fairly small quantities, which then creates a frenzy of consumer demand. Scores of people in any city where there’s an RSD-participating record store line up the night before, in hopes of snaring a particular record, and often they walk out with many other impulse purchases not on their original list. So what if you’re several hundred dollars poorer?

Today, consumers gladly shop at approximately 1,400 independent US record stores and another 3,000 doing business globally; Record Store Day is celebrated on every continent but Antarctica. While vinyl admittedly registered a negligible sales blip in the 1990s, the format never really went away, thanks to old-school DJs spinning dance records, audiophiles with their thousand-dollar-plus stereos supported by a few labels catering to that market, and flea-market crate diggers looking for collectibles. One person’s trash is another’s treasure, indeed. Those well-combed-over used record bins gave indie retailers confidence that perhaps vinyl still had some life in it.

Although Record Store Day exclusive releases are pressed in relatively low quantities of 15,000 or less, a non-RSD title like Jack White’s 2014 solo record, Lazaretto, proved that a new, non-reissue album can sell 230,000 units on vinyl. Third Man Records head Ben Blackwell gave me the sales figure, as of March 2020. The Arctic Monkeys’ AM was the second best-selling album on vinyl with 29,000 units that year. But the vinyl world was not nearly as large in 2014 as it is 2022. I have no doubt that a new album from Taylor Swift or Beyonce, who appeal to a younger demographic, could sell hundreds of thousands of copies in the new decade ahead.

Isn’t it interesting that record stores never ceased to be called “record stores” even when they were selling mostly compact discs? To understand why Vinyl 2.0 is working, we must hark back to the early 1980s when the industry replaced the LP with the shiny little disc known as the CD. As noted at the beginning of the chapter, retailers could return unsold CDs, which gave them an incentive to usher in a new format, but no longer would labels and distributors accept vinyl.

Nearly a quarter century later, when approached by the RSD cofounders about their vision, the major labels attached strings for the indie retailers and distributors if they were going to insist on bringing back v...